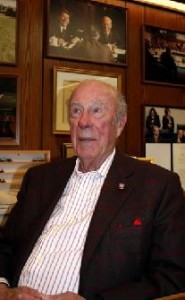

Interview with former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz

Mar. 2, 2009

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

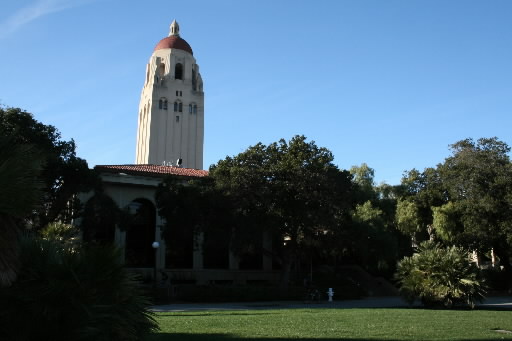

At Stanford University’s Hoover Institution in the United States, former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz, 88, was interviewed by the Chugoku Shimbun and stressed that action toward the abolition of nuclear weapons will make the world more secure. Mr. Shultz was Secretary of State under the Reagan administration and is currently the Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow at the Hoover Institution. In January 2007 and January 2008, he and three other former high-ranking officials published opinion pieces in a U.S. newspaper that called for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This appeal for abolition by former warriors of the Cold War elicited a strong reaction worldwide.

In the op-ed pieces in the Wall Street Journal, you and three statesmen, former Senator Nunn, former Secretary of Defense Perry, and former Secretary of State Kissinger, called for “a world free of nuclear weapons.” Why did you decide to issue the essays in 2007 and 2008? Also, would you explain about the series of conferences in which you discussed the implication of the Reykjavik Summit in 1986 and the visions and steps toward “a world free of nuclear weapons”?

It started here at the Hoover Institution, where a colleague of mine, Sidney Drell, who is a physicist and a man who has long been interested in arms control, he and I decided we should have a conference on the 20th anniversary of the Reykjavik meeting between President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev.

I was at that meeting in a little room. President Reagan was on one end of the table, about half the length of this one. Gorbachev was on the other end, and I was sitting beside President Reagan, Shevardnadze sitting beside Gorbachev. We were there for two days, talking about everything. Among other things, at the end, there was an agreement that we should seek a world free of nuclear weapons, and I agreed with that.

The Reykjavik meeting did not come to closure because of a dispute about Strategic Defense. But, nevertheless, the subject was there. We thought we should have a conference on the 20th anniversary to examine the implications of what was talked about. We had an excellent conference, first-class people here. We discussed the issues that were talked about there. The idea of a world free of nuclear weapons became much more real. But we also said, you are not going to get there by just wishing for it, you have to have a program of actions, steps that would get you there. So we developed this op-ed for The Wall Street Journal.

What kind of reaction did you get?

The reaction to it around the world was very positive, very different from the reaction 20 years earlier. I wondered to myself what accounts for that difference. And I think, at the time of Reykjavik, the Cold War was very much there, and people thought that nuclear deterrence helped keep the peace. But Reagan thought that while that may be so, it also posed the threat of annihilation if you ever started a nuclear exchange. So he did not like it. But now, people have suddenly awakened to the fact that the subject has sort of fallen off the table since the end of the Cold War, and yet there are a lot of nuclear weapons around, and they are more and more carelessly administered. The terrorist groups want to get them, and more and more countries have them. And so the dangers are increasing that they might get used. And that would be a catastrophe.

So the reaction encouraged us to have a second conference, and this time, we commissioned papers on the various steps. And we had a riveting conference where we discussed these papers.

Then the second op-ed was issued and also got a favorable response.

We thought to ourselves that we should have a conference in some other country and invite people from other countries and see what kind of reaction we would get. And out of the clear blue sky, the government of Norway said: “If you come to Oslo, we would like to hold a conference.” So that’s why it took place in Oslo. There were 29 countries represented there, including all the countries that have nuclear weapons, including Israel, and lots of countries that could easily have them if they wanted to, like Japan and Germany. It was a very constructive discussion. Then we had some discussions with Russian officials, who were also quite amenable to discussion of this issue. So we had a feeling that there is beginning to be real motion.

Are there some who are not happy with your articles?

Oh, yes. There are people who oppose the idea and think that the goal is visionary and can’t be achieved, and who have a great continuing confidence in deterrence. But even people like that feel that many of the steps we have outlined would make the world safer. So in some cases they oppose the vision, but they support at least many of the steps. And we all think that the steps themselves would make the world safer.

What are the challenges for the Obama administration in regard to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation? What do you think he should do first?

Well, of course, the president takes office, in any circumstances, with a big agenda. But president Obama has a particularly daunting challenge, because of the turmoil involving not only our economy but also economies all over the world. So he is bound to be preoccupied with that issue. But international issues are also there. He has appointed a strong national security team. How they will decide to approach this, I don’t know. But I know that he has on his mind how important this is. And there are members of Congress who agree. Senator Feinstein from California had an article expressing her belief in this idea.

My next question is regarding Hiroshima and Japan. As a country with the experience of nuclear disaster, what would be Japan’s role in pursing the elimination of nuclear weapons in the world? A world free of nuclear weapons would be a world without the nuclear umbrella, too. When will we have to abandon the nuclear umbrella, which the U.S. provides for its allies, including Japan, in order to reach the top of the mountain?

Japan is an extremely important country. It is important because of its strong economy, it is important because of its very extraordinarily capable people. And it is important in this setting because, on one hand, Japan could clearly have a nuclear weapon tomorrow if it decided that it wanted to have one. But it doesn’t want to have one because, of all the countries in the world, it had the experience of seeing what kind of damage a relatively small nuclear weapons, by today’s standard, can do. So I think Japan has a lot of credibility to stand and speak on the issue. And be part of the effort to make this global enterprise. It can’t go anywhere with just the U.S. program to try to get people’s support. It’s got to be a global enterprise.

The reason Japan needs a nuclear umbrella is that there are countries, just like the Soviet Union during the Cold War, who have nuclear weapons and could use them on Japan, but are deterred from doing that because of the U.S. nuclear umbrella, meaning that they are deterred because they know that the U.S. will retaliate against them. That is the function of the umbrella. If all countries get rid of all of their nuclear weapons, then the threat of a nuclear weapon against Japan is removed, so you don’t need the nuclear umbrella any more, because there is no nuclear weapon to come at you. So that doesn’t mean the military force disappears in the world. The conventional force will remain. Japan has very strong defense forces.

Have you ever considered visiting Hiroshima and sharing your ambitious views with the citizens?

I have never had the opportunity to visit, but I can remember, after World War II, seeing the pictures of it. And the pictures made a deep impact on me. You see the damage one single bomb can do. Then you read that people have figured out how to make nuclear bombs that are a hundred times more powerful. And you say to yourself, that’s unimaginable.

Have those pictures of Hiroshima motivated you to push yourself towards “a world free of nuclear weapons”?

Yes, it’s the image that stays with you. You say to yourself “we don’t want this to happen again.”

I could remember Henry Kissinger, in one of the meetings we had on this subject, said: “The thing that I agonized the most about and worried most about was what would I say to the president if my advice was whether to use a nuclear weapon. Who thinks you should have the power to decide to kill a million people? You drop the bomb on a populous city somewhere, that’s what would happen. Who do you think you are, are you god? You are not. The sense he’s saying is “this weapon is so terrible that a person with any conscience wouldn’t use it.” But before it was really understood, it was used. But now people understand that a lot better. And I am sure that there are people who wouldn’t hesitate to use it, but those people are the ones we don’t want to have get their hands on one. But the pictures of Hiroshima that I saw after the war, I can visualize them all and they say to you, this is such destruction.

(Originally published on February 11, 2009)

At Stanford University’s Hoover Institution in the United States, former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz, 88, was interviewed by the Chugoku Shimbun and stressed that action toward the abolition of nuclear weapons will make the world more secure. Mr. Shultz was Secretary of State under the Reagan administration and is currently the Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow at the Hoover Institution. In January 2007 and January 2008, he and three other former high-ranking officials published opinion pieces in a U.S. newspaper that called for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This appeal for abolition by former warriors of the Cold War elicited a strong reaction worldwide.

In the op-ed pieces in the Wall Street Journal, you and three statesmen, former Senator Nunn, former Secretary of Defense Perry, and former Secretary of State Kissinger, called for “a world free of nuclear weapons.” Why did you decide to issue the essays in 2007 and 2008? Also, would you explain about the series of conferences in which you discussed the implication of the Reykjavik Summit in 1986 and the visions and steps toward “a world free of nuclear weapons”?

It started here at the Hoover Institution, where a colleague of mine, Sidney Drell, who is a physicist and a man who has long been interested in arms control, he and I decided we should have a conference on the 20th anniversary of the Reykjavik meeting between President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev.

I was at that meeting in a little room. President Reagan was on one end of the table, about half the length of this one. Gorbachev was on the other end, and I was sitting beside President Reagan, Shevardnadze sitting beside Gorbachev. We were there for two days, talking about everything. Among other things, at the end, there was an agreement that we should seek a world free of nuclear weapons, and I agreed with that.

The Reykjavik meeting did not come to closure because of a dispute about Strategic Defense. But, nevertheless, the subject was there. We thought we should have a conference on the 20th anniversary to examine the implications of what was talked about. We had an excellent conference, first-class people here. We discussed the issues that were talked about there. The idea of a world free of nuclear weapons became much more real. But we also said, you are not going to get there by just wishing for it, you have to have a program of actions, steps that would get you there. So we developed this op-ed for The Wall Street Journal.

What kind of reaction did you get?

The reaction to it around the world was very positive, very different from the reaction 20 years earlier. I wondered to myself what accounts for that difference. And I think, at the time of Reykjavik, the Cold War was very much there, and people thought that nuclear deterrence helped keep the peace. But Reagan thought that while that may be so, it also posed the threat of annihilation if you ever started a nuclear exchange. So he did not like it. But now, people have suddenly awakened to the fact that the subject has sort of fallen off the table since the end of the Cold War, and yet there are a lot of nuclear weapons around, and they are more and more carelessly administered. The terrorist groups want to get them, and more and more countries have them. And so the dangers are increasing that they might get used. And that would be a catastrophe.

So the reaction encouraged us to have a second conference, and this time, we commissioned papers on the various steps. And we had a riveting conference where we discussed these papers.

Then the second op-ed was issued and also got a favorable response.

We thought to ourselves that we should have a conference in some other country and invite people from other countries and see what kind of reaction we would get. And out of the clear blue sky, the government of Norway said: “If you come to Oslo, we would like to hold a conference.” So that’s why it took place in Oslo. There were 29 countries represented there, including all the countries that have nuclear weapons, including Israel, and lots of countries that could easily have them if they wanted to, like Japan and Germany. It was a very constructive discussion. Then we had some discussions with Russian officials, who were also quite amenable to discussion of this issue. So we had a feeling that there is beginning to be real motion.

Are there some who are not happy with your articles?

Oh, yes. There are people who oppose the idea and think that the goal is visionary and can’t be achieved, and who have a great continuing confidence in deterrence. But even people like that feel that many of the steps we have outlined would make the world safer. So in some cases they oppose the vision, but they support at least many of the steps. And we all think that the steps themselves would make the world safer.

What are the challenges for the Obama administration in regard to nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation? What do you think he should do first?

Well, of course, the president takes office, in any circumstances, with a big agenda. But president Obama has a particularly daunting challenge, because of the turmoil involving not only our economy but also economies all over the world. So he is bound to be preoccupied with that issue. But international issues are also there. He has appointed a strong national security team. How they will decide to approach this, I don’t know. But I know that he has on his mind how important this is. And there are members of Congress who agree. Senator Feinstein from California had an article expressing her belief in this idea.

My next question is regarding Hiroshima and Japan. As a country with the experience of nuclear disaster, what would be Japan’s role in pursing the elimination of nuclear weapons in the world? A world free of nuclear weapons would be a world without the nuclear umbrella, too. When will we have to abandon the nuclear umbrella, which the U.S. provides for its allies, including Japan, in order to reach the top of the mountain?

Japan is an extremely important country. It is important because of its strong economy, it is important because of its very extraordinarily capable people. And it is important in this setting because, on one hand, Japan could clearly have a nuclear weapon tomorrow if it decided that it wanted to have one. But it doesn’t want to have one because, of all the countries in the world, it had the experience of seeing what kind of damage a relatively small nuclear weapons, by today’s standard, can do. So I think Japan has a lot of credibility to stand and speak on the issue. And be part of the effort to make this global enterprise. It can’t go anywhere with just the U.S. program to try to get people’s support. It’s got to be a global enterprise.

The reason Japan needs a nuclear umbrella is that there are countries, just like the Soviet Union during the Cold War, who have nuclear weapons and could use them on Japan, but are deterred from doing that because of the U.S. nuclear umbrella, meaning that they are deterred because they know that the U.S. will retaliate against them. That is the function of the umbrella. If all countries get rid of all of their nuclear weapons, then the threat of a nuclear weapon against Japan is removed, so you don’t need the nuclear umbrella any more, because there is no nuclear weapon to come at you. So that doesn’t mean the military force disappears in the world. The conventional force will remain. Japan has very strong defense forces.

Have you ever considered visiting Hiroshima and sharing your ambitious views with the citizens?

I have never had the opportunity to visit, but I can remember, after World War II, seeing the pictures of it. And the pictures made a deep impact on me. You see the damage one single bomb can do. Then you read that people have figured out how to make nuclear bombs that are a hundred times more powerful. And you say to yourself, that’s unimaginable.

Have those pictures of Hiroshima motivated you to push yourself towards “a world free of nuclear weapons”?

Yes, it’s the image that stays with you. You say to yourself “we don’t want this to happen again.”

I could remember Henry Kissinger, in one of the meetings we had on this subject, said: “The thing that I agonized the most about and worried most about was what would I say to the president if my advice was whether to use a nuclear weapon. Who thinks you should have the power to decide to kill a million people? You drop the bomb on a populous city somewhere, that’s what would happen. Who do you think you are, are you god? You are not. The sense he’s saying is “this weapon is so terrible that a person with any conscience wouldn’t use it.” But before it was really understood, it was used. But now people understand that a lot better. And I am sure that there are people who wouldn’t hesitate to use it, but those people are the ones we don’t want to have get their hands on one. But the pictures of Hiroshima that I saw after the war, I can visualize them all and they say to you, this is such destruction.

(Originally published on February 11, 2009)