Translations of "Children of the Atomic Bomb" grow in number

Nov. 20, 2009

by Toshiko Bajo, Staff Writer

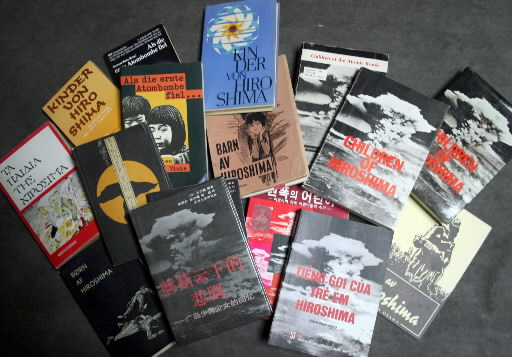

Nearly 60 years after the publication of the first edition, Children of the Atomic Bomb, a collection of essays by children who experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, continues to gain readers throughout the world. New editions in Indonesian and Russian that were published this year brought the total number of translations to 13. The Chugoku Shimbun asked some of those who wrote essays for the book or who were involved in its publication to talk about their memories of the collection, which continues to find new readers both in Japan and abroad.

Children of the Atomic Bomb was first published in 1951 by Iwanami Shoten. The book was edited by Arata Osada (1887-1961), a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University known for his research into Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and some of his students. A translation into Esperanto the following year was followed by editions in such Western languages as English, Norwegian, Danish and German.

The book continued to be translated into other languages following Mr. Osada's death. In 1989 the late Yutaka Okihara (who passed away in 2004), former president of Hiroshima University and a one-time student of Mr. Osada, led an effort to translate the book into Chinese. It was subsequently translated into Korean and Vietnamese as well.

The new Indonesian edition contains 11 essays, while the Russian edition has 44. Both editions were published through the efforts Goro Osada, Mr. Arata's fourth son, along with some of his former students and acquaintances. Mr. Osada, 82, a professor emeritus of economics at Yokohama City University and a resident of Tokyo, has been involved in the project since the publication of the first Japanese edition.

Why has the book continued to find new readers throughout the world? Yuriko Hayashi (nee Yamamura), 73, a Hiroshima resident and president of the Oleander Association for the Children of the Atomic Bomb, is one of those who submitted an essay when she was in the third year of junior high school. She described her experience of the bombing as a 9-year-old:

"Just then a person completely covered with blood was carried on a stretcher along the road out front… He was bright red from the top of his head to the bottoms of his feet, with hardly a white spot anywhere."

"…there were more and more dead people lying all around, and I couldn't possibly help seeing them… Every time I saw one of them I couldn't help crying."

"It was painful to recall those events," Ms. Hayashi said, recalling those days. "But I was able to face my experiences head on." She added, "It's wonderful that the book continues to find new readers overseas. I want them to understand the horror that a single atomic bomb can bring about and to imagine what it would be like if their children or descendants were to have such an experience."

The publication of the book was not the end of the story. In 1952 those who had submitted essays for the book joined supporters in forming Friends of the Children of the Atomic Bomb. Through the performance of plays and personal accounts of the bombing, the group has continued to convey the atomic bombing experience. "We all shared the same pain," said Ms. Hayashi. "We were able to understand each other, and that was a comfort."

What was your experience of the atomic bombing?

At the time I was attending a course in preparation for entering Tokyo College of Commerce (now Hitotsubashi University). I decided to go see my father before going into the military, so I returned to Hiroshima on August 3. I was at home in the Hiratsuka District on August 6 when the atomic bomb was dropped. I pulled my father, who had been on the veranda, out from under the collapsed house. He had been pierced by shards of glass and had more than 50 wounds all over his body. I carried him to safety. It's almost a miracle that I was able to save him. I wouldn't have been surprised if he had died. That was the greatest service I ever performed for my father. Despite suffering from the aftereffects of the bombing, after that my father was able to publish books and devote himself to the peace movement.

How did you get involved in the editing and publication of Children of the Atomic Bomb?

Most of the editing was done by my father and my brother along with college students. I gathered the photos for the first edition. When the book was published, my father was worried that he would be fired from his job as a professor at Hiroshima University for putting out a book that was likely to encounter opposition from the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers. Fortunately, nothing happened, maybe because the essays were written by children, not adults.

What are you going to do next?

I want many more people to read the book. Some of my students have come up with a plan to translate it into even more languages. There are fewer and fewer opportunities to use the book for peace education and other purposes, but it must not be forgotten.

Many peace activists participated in the movement while looking to the book for moral support. It also inspired many of its readers as well as those who wrote the essays to get involved in peace activities. In his letters my father always wrote, "I am battling against war." I want many people to continue to have that kind of passion.

Do you recall how you came to write your essay?

In Japanese class the teacher urged all of us to write an essay. I thought it was a homework assignment, so I wrote one. Ordinarily we used coarse writing paper, but that time we were given a sheet of nice manuscript paper, so I felt I had to write a proper essay.

Why did you serve as vice president of Friends of the Children of the Atomic Bomb?

I was lonesome. My mother and younger brother, who were in our house next to the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-bomb Dome), were killed instantly in the bombing. My father was in a nearby air-raid shelter. He was seriously injured and died 10 days later.

I was very involved in the activities of the group, which brought together people who had had similar experiences. I went to Tokyo and Osaka to present lectures and plays. It was so fulfilling that I neglected my studies. I also appeared in the film "Hiroshima." That got me interested in films, which led me to become a film writer.

But under the direction of adults, the innocent activities of children gradually took on a political tinge. Because of my activities, I couldn't get a recommendation for admission to high school, and I realized I was once again going to suffer on account of the atomic bombing. So I entered a high school in Yamaguchi, where my mother was from. I didn't participate in the peace movement again until I was almost 60 years old.

What are your hopes for the future for Children of the Atomic Bomb?

It's wonderful that our essays are being read by people throughout the world. Among all the literature on the atomic bombing, I don't think there's any other literature that has described the atomic bomb experience as well. If the original essays, including those that weren't included in the book, could be found they would be cultural assets. I hope they'll turn up.

I think it might be a good idea to create a fund to support the atomic bomb survivors using the royalties from the book. Even now there are people who were orphaned by the bomb and who are struggling financially. By supporting them I think we could get back to Arata Osada's original idea behind the creation of Children of the Atomic Bomb.

The B6 size, 306-page Children of the Atomic Bomb is a collection of 105 essays about the atomic bombing. They were selected from 1,175 essays written by students from the fourth grade of elementary school through college.

"Grandmother took the little box out of the rucksack and showed it to them all. What she showed them was only Mother's gold tooth and the bone of her elbow. Even then I didn't understand." (6th grade girl, 6 years old in 1945)

The book's 40-page preface includes excerpts from another 84 essays. In the preface, Arata Osada described the children's essays as "crystals with blood and tears; outrage against the war that took their beloved family members from them; and a heart-rending prayer and call for peace."

In 1951, when the first edition was published, all forms of media in Japan were subject to censorship by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). These simple, truthful essays continue to be read in Japan, and the Japanese edition has had more than 50 printings. A pocket edition has also been published.

Children of the Atomic Bomb has been adapted for the screen twice, first with its original title under director Kaneto Shindo in 1952 and again the following year as "Hiroshima" under director Hideo Sekikawa.

The whereabouts of the original essays is unknown.

(Originally published Nov. 16, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

Essays about atomic bombing now in 13 languages

Nearly 60 years after the publication of the first edition, Children of the Atomic Bomb, a collection of essays by children who experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, continues to gain readers throughout the world. New editions in Indonesian and Russian that were published this year brought the total number of translations to 13. The Chugoku Shimbun asked some of those who wrote essays for the book or who were involved in its publication to talk about their memories of the collection, which continues to find new readers both in Japan and abroad.

Children of the Atomic Bomb was first published in 1951 by Iwanami Shoten. The book was edited by Arata Osada (1887-1961), a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University known for his research into Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and some of his students. A translation into Esperanto the following year was followed by editions in such Western languages as English, Norwegian, Danish and German.

The book continued to be translated into other languages following Mr. Osada's death. In 1989 the late Yutaka Okihara (who passed away in 2004), former president of Hiroshima University and a one-time student of Mr. Osada, led an effort to translate the book into Chinese. It was subsequently translated into Korean and Vietnamese as well.

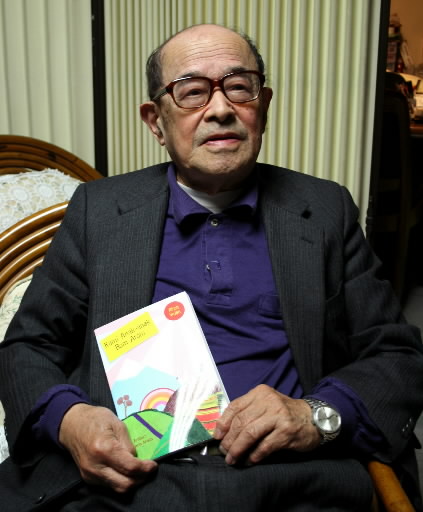

The new Indonesian edition contains 11 essays, while the Russian edition has 44. Both editions were published through the efforts Goro Osada, Mr. Arata's fourth son, along with some of his former students and acquaintances. Mr. Osada, 82, a professor emeritus of economics at Yokohama City University and a resident of Tokyo, has been involved in the project since the publication of the first Japanese edition.

Why has the book continued to find new readers throughout the world? Yuriko Hayashi (nee Yamamura), 73, a Hiroshima resident and president of the Oleander Association for the Children of the Atomic Bomb, is one of those who submitted an essay when she was in the third year of junior high school. She described her experience of the bombing as a 9-year-old:

"Just then a person completely covered with blood was carried on a stretcher along the road out front… He was bright red from the top of his head to the bottoms of his feet, with hardly a white spot anywhere."

"…there were more and more dead people lying all around, and I couldn't possibly help seeing them… Every time I saw one of them I couldn't help crying."

"It was painful to recall those events," Ms. Hayashi said, recalling those days. "But I was able to face my experiences head on." She added, "It's wonderful that the book continues to find new readers overseas. I want them to understand the horror that a single atomic bomb can bring about and to imagine what it would be like if their children or descendants were to have such an experience."

The publication of the book was not the end of the story. In 1952 those who had submitted essays for the book joined supporters in forming Friends of the Children of the Atomic Bomb. Through the performance of plays and personal accounts of the bombing, the group has continued to convey the atomic bombing experience. "We all shared the same pain," said Ms. Hayashi. "We were able to understand each other, and that was a comfort."

Goro Osada, carrying on in the spirit of his father, works to publish foreign-language editions

What was your experience of the atomic bombing?

At the time I was attending a course in preparation for entering Tokyo College of Commerce (now Hitotsubashi University). I decided to go see my father before going into the military, so I returned to Hiroshima on August 3. I was at home in the Hiratsuka District on August 6 when the atomic bomb was dropped. I pulled my father, who had been on the veranda, out from under the collapsed house. He had been pierced by shards of glass and had more than 50 wounds all over his body. I carried him to safety. It's almost a miracle that I was able to save him. I wouldn't have been surprised if he had died. That was the greatest service I ever performed for my father. Despite suffering from the aftereffects of the bombing, after that my father was able to publish books and devote himself to the peace movement.

How did you get involved in the editing and publication of Children of the Atomic Bomb?

Most of the editing was done by my father and my brother along with college students. I gathered the photos for the first edition. When the book was published, my father was worried that he would be fired from his job as a professor at Hiroshima University for putting out a book that was likely to encounter opposition from the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers. Fortunately, nothing happened, maybe because the essays were written by children, not adults.

What are you going to do next?

I want many more people to read the book. Some of my students have come up with a plan to translate it into even more languages. There are fewer and fewer opportunities to use the book for peace education and other purposes, but it must not be forgotten.

Many peace activists participated in the movement while looking to the book for moral support. It also inspired many of its readers as well as those who wrote the essays to get involved in peace activities. In his letters my father always wrote, "I am battling against war." I want many people to continue to have that kind of passion.

Masaaki (real first name: Toshihiko) Tanabe, 71, writer of one of the essays and a resident of Hiroshima

Do you recall how you came to write your essay?

In Japanese class the teacher urged all of us to write an essay. I thought it was a homework assignment, so I wrote one. Ordinarily we used coarse writing paper, but that time we were given a sheet of nice manuscript paper, so I felt I had to write a proper essay.

Why did you serve as vice president of Friends of the Children of the Atomic Bomb?

I was lonesome. My mother and younger brother, who were in our house next to the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-bomb Dome), were killed instantly in the bombing. My father was in a nearby air-raid shelter. He was seriously injured and died 10 days later.

I was very involved in the activities of the group, which brought together people who had had similar experiences. I went to Tokyo and Osaka to present lectures and plays. It was so fulfilling that I neglected my studies. I also appeared in the film "Hiroshima." That got me interested in films, which led me to become a film writer.

But under the direction of adults, the innocent activities of children gradually took on a political tinge. Because of my activities, I couldn't get a recommendation for admission to high school, and I realized I was once again going to suffer on account of the atomic bombing. So I entered a high school in Yamaguchi, where my mother was from. I didn't participate in the peace movement again until I was almost 60 years old.

What are your hopes for the future for Children of the Atomic Bomb?

It's wonderful that our essays are being read by people throughout the world. Among all the literature on the atomic bombing, I don't think there's any other literature that has described the atomic bomb experience as well. If the original essays, including those that weren't included in the book, could be found they would be cultural assets. I hope they'll turn up.

I think it might be a good idea to create a fund to support the atomic bomb survivors using the royalties from the book. Even now there are people who were orphaned by the bomb and who are struggling financially. By supporting them I think we could get back to Arata Osada's original idea behind the creation of Children of the Atomic Bomb.

First edition published in 1951, movie version also made

The B6 size, 306-page Children of the Atomic Bomb is a collection of 105 essays about the atomic bombing. They were selected from 1,175 essays written by students from the fourth grade of elementary school through college.

"Grandmother took the little box out of the rucksack and showed it to them all. What she showed them was only Mother's gold tooth and the bone of her elbow. Even then I didn't understand." (6th grade girl, 6 years old in 1945)

The book's 40-page preface includes excerpts from another 84 essays. In the preface, Arata Osada described the children's essays as "crystals with blood and tears; outrage against the war that took their beloved family members from them; and a heart-rending prayer and call for peace."

In 1951, when the first edition was published, all forms of media in Japan were subject to censorship by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). These simple, truthful essays continue to be read in Japan, and the Japanese edition has had more than 50 printings. A pocket edition has also been published.

Children of the Atomic Bomb has been adapted for the screen twice, first with its original title under director Kaneto Shindo in 1952 and again the following year as "Hiroshima" under director Hideo Sekikawa.

The whereabouts of the original essays is unknown.

(Originally published Nov. 16, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.