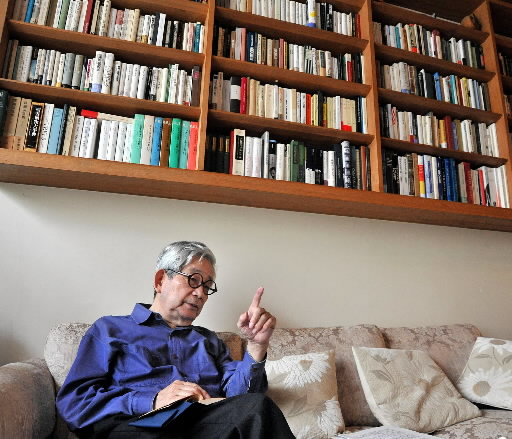

Nobel Prize novelist Kenzaburo Oe talks about "Hiroshima"

Oct. 16, 2010

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Nobel Prize winning writer Kenzaburo Oe, 75, has long reflected on the disaster caused by the atomic bombings, the human suffering and renewal, in relation to his own life. Following a speech he made on October 2 in downtown Hiroshima, for a public lecture series organized by the City of Hiroshima and the Hiroshima Culture Foundation under the title "Conveying the Peace Philosophy of Hiroshima," Mr. Oe granted an interview to the Chugoku Shimbun at his home in Setagaya Ward, Tokyo on October 5. How can we face up to a world in which nuclear weapons and their ultimate violence exist and proliferate? Mr. Oe's thoughts, shared over the course of three hours, have been summarized.

In 1960, when the revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty shook the archipelago of Japan, Mr. Oe visited the A-bombed city of Hiroshima for the first time, a city which he now describes as the "basis" for his life. He attended the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony on August 6 in 1960 and met with local writers and others. Mr. Oe's original encounter with Hiroshima dates back to a short story left by Tamiki Hara.

When I was reading through my notebooks a while ago, I remembered. At the age of 16, I became conscious of the fact that Hiroshima is an important place. I grew up in a town in Ehime Prefecture, a child who believed in militarism, but I felt attracted to democracy in the post-war period, the idea that people had the freedom to do what they wanted. With the understanding of my mother and older brother, I changed to Matsuyama Higashi High School, and became friends with Mr. Itami (the late Juzo Itami, a film director, actor, and older brother of Yukari, Mr. Oe's wife), who taught me a lot about literature. He told me that a writer who experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima committed suicide.

I knew some about the atomic bombings, but I was surprised that the sort of agony that could drive a writer to his death had persisted. Though I wanted to read his work, a literary magazine was expensive for me; at the time, I was eating only bread for lunch. Mr. Itami told me the magazine was in the library and so I read "Shingan no Kuni" ("The Land of the Heart's Desire") in the May 1951 issue of "Gunzo Magazine."

"Toward the completely unpredictable future, whether annihilation or salvation... However, a serene spring resonates at the bottom of the heart of each person." I was moved by this passage. The author also cited words from "The Pensées": "We have an instinct which we cannot repress, and which lifts us up."

I thought "All right, I'll read more of his writing, go to university and study Blaise Pascal, and learn from Kazuo Watanabe," a scholar of French literature and a professor at the University of Tokyo, whose books I was reading at the time. I entered the university, read books by Jean-Paul Sartre and others, and became a writer after my "Kimyo na Shigoto" ("The Strange Work") was carried in a university newspaper. There were many literary etudes in which I wrote about my childhood memories. One story involved the funny feeling of killing an ant on the grounds of a shrine. When I was reading through my notebooks, I remembered that I wrote that story having been influenced by Tamiki Hara.

Mr. Hara wondered about his perception of the world. With the suffering of his A-bomb experience at the root of this question, he longed to feel that "serene spring." I think that "Shingan no Kuni" and Tamiki Hara have been the starting point of my own writing from the time I thought "Oh, this is literature" as a 16-year-old boy until now as an old man of 75.

Those who do not surrender: Models for living

In "Hiroshima Noto" ("Hiroshima Notes"), published in 1965, Mr. Oe pointed to the atomic bombings and said that those "who never surrender to any situation" were "authentic" Japanese. On October 2, in his lecture entitled "What I Learned 'After Hiroshima'," Mr. Oe shared thoughts that he cultivated through dialogues with Fumio Shigeto, among others, who was the first president of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital and died in 1982.

As I wrote in the prologue to the book, my newly-born son was mentally disabled and I left for Hiroshima, feeling devastated. At the World Conference Against A & H Bombs of that year, the ninth such conference in August 1963, delegates of the Soviet Union and China were at odds over whether to oppose nuclear tests by any nation, while so many quarrels were occurring among the Japanese participants as well. Toshihiro Kanai, a journalist who used words precisely, described the situation as "a religious war of peace activists." (Mr. Kanai was the former chief editorial writer of the Chugoku Shimbun and died in 1974).

I think that Mr. Kanai's words at a 1964 conference involving A-bomb and H-bomb sufferers--"Have the atomic bombs come to be known for their power, or for their human tragedy?"--are still the most accurate characterization, even now. In nuclear weapons, he saw the tragedy suffered by human beings, rather than their power, and he thought deeply about this issue. I believed this was the direction that Japan should take and so I supported the campaign to compile a white paper on the A-bomb damage, which Mr. Kanai advocated.

Dr. Shigeto became engaged in treatment from the very day he was exposed to the atomic bombing. He was quick to notice the connection between radiation damage and leukemia, despite lacking data and statistics. Dr. Shigeto encouraged a young doctor, the late Takuso Yamawaki, to undertake research on the connection and the link was made between radiation damage and leukemia. It can be said that they discovered A-bomb disease. That was because Dr. Shigeto, in his younger days, worked on the research that exposed a mouse to radiation, starting from the repair of an X-ray machine.

But Dr. Shigeto did not praise his own success. Even when we jointly published "Taiwa: Genbakugo no Ningen" ("Dialogue: Humans Beings After the Atomic Bombings") in 1971, he said "My peculiar experience was helpful" and "It feels like a coincidence." I could not mention this in my lecture due to the lack of time, but I wanted to convey this point to young people.

If a person gives serious attention to the work at hand, understands it clearly, makes it a part of body and soul, and connects such studies and accumulated knowledge to real problems, the result will be a fine and important effort.

I have learned in Hiroshima that this is how human beings can live. The people of Hiroshima have not surrendered. Despite suffering from the atomic bombing, they have recovered and accomplished their tasks. Including Dr. Shigeto, I have met a number of people I should call "unknown warriors." I took my cue from them in order to get back on my feet as a young father. I linked their way of living with how I should live with my son, Hikari. Reflecting on Hiroshima became the basis for my life and for my literature. This means that I think and write by returning to models of human beings, and reflect these models in my writing.

In "Hiroshima Notes," there are expressions for which I, as a young writer, invented certain words. This is a matter of my expression. However, I don't think the view that the book "makes saints" of A-bomb survivors is accurate. Word came today that the book has reached its 86th edition. This edition has been printed in the same form as the original first edition, while the book has been translated into English and French, as well as into Italian two years ago. I can say that this is my only book on the market which has been well-loved for such a long time. (According to Iwanami Shoten publishing company, the publisher of "Hiroshima Notes," the total number of copies sold has reached roughly 810,000.)

Thoughts on peace and action: Think and express as human beings

Students who listened to Mr. Oe's lecture in Hiroshima pointed to the difficulty of carrying on the memory of the atomic bombing and the lack of positive signs concerning nuclear abolition: "I don't sense that the people of my generation are thinking about this issue" and "I wonder if simply collecting signatures can really lead to peace." What are Mr. Oe's current thoughts on peace and action?

Our thoughts and reflections on peace and action should go back to August 6, 1945, or the starting point of the nuclear age. Though relief measures for A-bomb survivors have gradually been achieved, the recognition of A-bomb diseases has made little progress in the 65 years since the bombing. Nuclear weapons, which can destroy the whole world, still threaten us today. Helping those still suffering from the atomic bombings and eliminating nuclear weapons are fundamentally fresh themes and they continue to exist as problems confronting human beings.

In order for young people to encounter Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they should see "Chichi to Kuraseba" ("The Face of Jizo"), a play by Hisashi Inoue, or read "Akikan" ("The Empty Can") by Kyoko Hayashi. Furthermore, they can read "Kuroi Ame" ("Black Rain") by Masuji Ibuse or actually listen to the experience of an A-bomb survivor. Then, they will think about their own future and the future of their children and other human beings. They will never stand on the side of killers.

Thinking about what it means to live as a human being, thinking "I want to live this way," these are the thoughts and the starting point. The moment we believe we do not have any thoughts, the thoughts are in fact developing. The thoughts are growing.

If I had given a title to this series of public lectures, I would have named it "Conveying to you what I regard as Hiroshima's thoughts on peace," since the foundation of creative activities is the desire to convey what one thinks to other people. If young people link the issues of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Okinawa with the footing on which they now stand, think how they will live, and convey this to others, these will be the very thoughts of peace.

I told myself many times that I would write a novel about Hiroshima and the nuclear situation. But I couldn't finish anything that focused on Hiroshima; it only found its way into hidden themes in some of my "late work." I was just reading the French translation of "Chichi to Kuraseba" by Hisashi Inoue. He was brilliant. He wrote about Hiroshima, without fail, right up to his death.

I'm spending my later years as a writer feeling depressed. I'm afraid that I will die as someone whose writing and statements have not played a real role in the elimination of nuclear weapons. However, I have not stopped thinking about the issues raised by Hiroshima.

"Shingan no Kuni," which I read at the age of 16, pierced my heart as a point for living. It was connected to the point of Professor Watanabe at the university, to the points of Dr. Shigeto and Mr. Kanai in Hiroshima, and eventually to the point of my late friend, the critic Edward Said. I think that I myself exist as a human being surrounded by those people.

A doctor said that we would not see significant development in Hikari, my mentally-challenged son. But before we knew it, he came to express his own unique nature. He expressed this not in words, but in music. As Pascal said, human beings have "an instinct which lifts us up." I think living involves rising higher, not walking on the same plane.

The end of the Cold War in the 1990s was an opportunity to eliminate nuclear weapons; instead, nuclear arms have proliferated. A new version of "Kakujidai no sozoryoku" ("Imagining the Atomic Age") was published in 2007 and a new epilogue entitled "Kagirinaku oawarini chikai michinakaba no epirogu" ("Close to the end, an epilogue half-done") was added to the series of lectures made by Mr. Oe in Tokyo in 1968. In this epilogue, he refers to the emerging danger of terrorists wielding smaller-sized nuclear weapons.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States, a certain peril lurking behind the nuclear regime primed by that nation, or nuclear authority if I may borrow the expression of Toshihiro Kanai, has grown. Terrorists might take advantage of such circumstances to obtain nuclear weapons, and a nuclear incident may occur.

U.S. President Barack Obama called for "a world without nuclear weapons" in a speech he made in Prague in April 2009, shortly after he assumed the presidency. Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who had been a supporter of the nuclear regime, and top officials of the British government, among others, began speaking out about nuclear abolition. All this has transpired because real politics, which seem rigid but are not, were forced into action. All those people have come to believe that nuclear weapons are no longer as effective as they once thought.

The leaders of these nations have begun thinking about "nuclear abolition" from the viewpoint of those who possess the power of nuclear weapons, not from the perspective of A-bomb survivors and their supporters, who have continued to stress that nuclear weapons bring about horrific consequences to human life. Though their starting point is different from ours, this is fine since nuclear arms, which annihilate human life, must be eliminated.

To advance the cause of nuclear abolition, Japan must completely abide by the three non-nuclear principles. Japan should enshrine the principles into law and never allow Okinawa to become a point of transit for nuclear weapons. Japan should call for the withdrawal of U.S. military forces stationed here, as a legal issue. That would lead to the nullification of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, then other treaties, including economic treaties, could be pursued. Some say that nullification of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty would impact the stability of Asia. However, stability cannot be earned in Asia if Japan tolerates U.S. nuclear weapons while perceiving the nuclear arms of other nations as a threat. A new national campaign arising from Hiroshima is needed.

Devising the means to eliminate nuclear weapons on a global basis is a difficult task. How can the inequalities felt in the world, including among the nuclear weapon states, be overcome? Can the United Nations possibly establish a rigorous mechanism to prevent nuclear arms from ever falling in the hands of terrorists? If someone says that nuclear weapons can be eliminated in 10 years, I would like to ask: "Are you sure?" I do not have sufficient courage to set a target year for nuclear abolition. However, if I said that nuclear weapons could be eliminated in 30 years, which would be nearly 100 years after the atomic bombings, I would end up insulting the potential of human beings.

Edward Said took an optimistic view of the Palestinian issue. I also maintain hope for nuclear abolition because of the human penchant for effort. I can say that I believe abolition will be realized. Living for nuclear abolition means to see the issue of the atomic bombings as a universal issue for human beings without betraying those who perished in the bombings. It also means recovering the real meaning and power of the stereotyped expression the "heart of Hiroshima."

profile

Kenzaburo Oe

Mr. Oe was born in 1935 in Ehime Prefecture. While studying French literature at the University of Tokyo in 1958, he won the Akutagawa Award for "Shiiku" ("The Catch"). In 1994, Mr. Oe was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for creating "a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today" through "Kojinteki na Taiken" ("A Personal Matter"), "Man'engan'nen no Futtoboru" ("The Silent Cry"), and "Natsukashii Toshi eno Tegami" ("Letters to My Sweet Bygone Years"), among other works. Following "Sayonara Watashi no Honyo!" ("Farewell, My Books!") and other books, Mr. Oe published "Suishi" ("Death by Water") at the end of last year, in which he, in a forest on Shikoku Island, explored the spirit of the times his father, who died at the end of World War II, was alive.

(Originally published on October 10, 2010)

Nobel Prize winning writer Kenzaburo Oe, 75, has long reflected on the disaster caused by the atomic bombings, the human suffering and renewal, in relation to his own life. Following a speech he made on October 2 in downtown Hiroshima, for a public lecture series organized by the City of Hiroshima and the Hiroshima Culture Foundation under the title "Conveying the Peace Philosophy of Hiroshima," Mr. Oe granted an interview to the Chugoku Shimbun at his home in Setagaya Ward, Tokyo on October 5. How can we face up to a world in which nuclear weapons and their ultimate violence exist and proliferate? Mr. Oe's thoughts, shared over the course of three hours, have been summarized.

Encounter at age 16: Short story by Tamiki Hara as starting point

In 1960, when the revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty shook the archipelago of Japan, Mr. Oe visited the A-bombed city of Hiroshima for the first time, a city which he now describes as the "basis" for his life. He attended the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony on August 6 in 1960 and met with local writers and others. Mr. Oe's original encounter with Hiroshima dates back to a short story left by Tamiki Hara.

When I was reading through my notebooks a while ago, I remembered. At the age of 16, I became conscious of the fact that Hiroshima is an important place. I grew up in a town in Ehime Prefecture, a child who believed in militarism, but I felt attracted to democracy in the post-war period, the idea that people had the freedom to do what they wanted. With the understanding of my mother and older brother, I changed to Matsuyama Higashi High School, and became friends with Mr. Itami (the late Juzo Itami, a film director, actor, and older brother of Yukari, Mr. Oe's wife), who taught me a lot about literature. He told me that a writer who experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima committed suicide.

I knew some about the atomic bombings, but I was surprised that the sort of agony that could drive a writer to his death had persisted. Though I wanted to read his work, a literary magazine was expensive for me; at the time, I was eating only bread for lunch. Mr. Itami told me the magazine was in the library and so I read "Shingan no Kuni" ("The Land of the Heart's Desire") in the May 1951 issue of "Gunzo Magazine."

"Toward the completely unpredictable future, whether annihilation or salvation... However, a serene spring resonates at the bottom of the heart of each person." I was moved by this passage. The author also cited words from "The Pensées": "We have an instinct which we cannot repress, and which lifts us up."

I thought "All right, I'll read more of his writing, go to university and study Blaise Pascal, and learn from Kazuo Watanabe," a scholar of French literature and a professor at the University of Tokyo, whose books I was reading at the time. I entered the university, read books by Jean-Paul Sartre and others, and became a writer after my "Kimyo na Shigoto" ("The Strange Work") was carried in a university newspaper. There were many literary etudes in which I wrote about my childhood memories. One story involved the funny feeling of killing an ant on the grounds of a shrine. When I was reading through my notebooks, I remembered that I wrote that story having been influenced by Tamiki Hara.

Mr. Hara wondered about his perception of the world. With the suffering of his A-bomb experience at the root of this question, he longed to feel that "serene spring." I think that "Shingan no Kuni" and Tamiki Hara have been the starting point of my own writing from the time I thought "Oh, this is literature" as a 16-year-old boy until now as an old man of 75.

Those who do not surrender: Models for living

In "Hiroshima Noto" ("Hiroshima Notes"), published in 1965, Mr. Oe pointed to the atomic bombings and said that those "who never surrender to any situation" were "authentic" Japanese. On October 2, in his lecture entitled "What I Learned 'After Hiroshima'," Mr. Oe shared thoughts that he cultivated through dialogues with Fumio Shigeto, among others, who was the first president of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital and died in 1982.

As I wrote in the prologue to the book, my newly-born son was mentally disabled and I left for Hiroshima, feeling devastated. At the World Conference Against A & H Bombs of that year, the ninth such conference in August 1963, delegates of the Soviet Union and China were at odds over whether to oppose nuclear tests by any nation, while so many quarrels were occurring among the Japanese participants as well. Toshihiro Kanai, a journalist who used words precisely, described the situation as "a religious war of peace activists." (Mr. Kanai was the former chief editorial writer of the Chugoku Shimbun and died in 1974).

I think that Mr. Kanai's words at a 1964 conference involving A-bomb and H-bomb sufferers--"Have the atomic bombs come to be known for their power, or for their human tragedy?"--are still the most accurate characterization, even now. In nuclear weapons, he saw the tragedy suffered by human beings, rather than their power, and he thought deeply about this issue. I believed this was the direction that Japan should take and so I supported the campaign to compile a white paper on the A-bomb damage, which Mr. Kanai advocated.

Dr. Shigeto became engaged in treatment from the very day he was exposed to the atomic bombing. He was quick to notice the connection between radiation damage and leukemia, despite lacking data and statistics. Dr. Shigeto encouraged a young doctor, the late Takuso Yamawaki, to undertake research on the connection and the link was made between radiation damage and leukemia. It can be said that they discovered A-bomb disease. That was because Dr. Shigeto, in his younger days, worked on the research that exposed a mouse to radiation, starting from the repair of an X-ray machine.

But Dr. Shigeto did not praise his own success. Even when we jointly published "Taiwa: Genbakugo no Ningen" ("Dialogue: Humans Beings After the Atomic Bombings") in 1971, he said "My peculiar experience was helpful" and "It feels like a coincidence." I could not mention this in my lecture due to the lack of time, but I wanted to convey this point to young people.

If a person gives serious attention to the work at hand, understands it clearly, makes it a part of body and soul, and connects such studies and accumulated knowledge to real problems, the result will be a fine and important effort.

I have learned in Hiroshima that this is how human beings can live. The people of Hiroshima have not surrendered. Despite suffering from the atomic bombing, they have recovered and accomplished their tasks. Including Dr. Shigeto, I have met a number of people I should call "unknown warriors." I took my cue from them in order to get back on my feet as a young father. I linked their way of living with how I should live with my son, Hikari. Reflecting on Hiroshima became the basis for my life and for my literature. This means that I think and write by returning to models of human beings, and reflect these models in my writing.

In "Hiroshima Notes," there are expressions for which I, as a young writer, invented certain words. This is a matter of my expression. However, I don't think the view that the book "makes saints" of A-bomb survivors is accurate. Word came today that the book has reached its 86th edition. This edition has been printed in the same form as the original first edition, while the book has been translated into English and French, as well as into Italian two years ago. I can say that this is my only book on the market which has been well-loved for such a long time. (According to Iwanami Shoten publishing company, the publisher of "Hiroshima Notes," the total number of copies sold has reached roughly 810,000.)

Thoughts on peace and action: Think and express as human beings

Students who listened to Mr. Oe's lecture in Hiroshima pointed to the difficulty of carrying on the memory of the atomic bombing and the lack of positive signs concerning nuclear abolition: "I don't sense that the people of my generation are thinking about this issue" and "I wonder if simply collecting signatures can really lead to peace." What are Mr. Oe's current thoughts on peace and action?

Our thoughts and reflections on peace and action should go back to August 6, 1945, or the starting point of the nuclear age. Though relief measures for A-bomb survivors have gradually been achieved, the recognition of A-bomb diseases has made little progress in the 65 years since the bombing. Nuclear weapons, which can destroy the whole world, still threaten us today. Helping those still suffering from the atomic bombings and eliminating nuclear weapons are fundamentally fresh themes and they continue to exist as problems confronting human beings.

In order for young people to encounter Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they should see "Chichi to Kuraseba" ("The Face of Jizo"), a play by Hisashi Inoue, or read "Akikan" ("The Empty Can") by Kyoko Hayashi. Furthermore, they can read "Kuroi Ame" ("Black Rain") by Masuji Ibuse or actually listen to the experience of an A-bomb survivor. Then, they will think about their own future and the future of their children and other human beings. They will never stand on the side of killers.

Thinking about what it means to live as a human being, thinking "I want to live this way," these are the thoughts and the starting point. The moment we believe we do not have any thoughts, the thoughts are in fact developing. The thoughts are growing.

If I had given a title to this series of public lectures, I would have named it "Conveying to you what I regard as Hiroshima's thoughts on peace," since the foundation of creative activities is the desire to convey what one thinks to other people. If young people link the issues of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Okinawa with the footing on which they now stand, think how they will live, and convey this to others, these will be the very thoughts of peace.

I told myself many times that I would write a novel about Hiroshima and the nuclear situation. But I couldn't finish anything that focused on Hiroshima; it only found its way into hidden themes in some of my "late work." I was just reading the French translation of "Chichi to Kuraseba" by Hisashi Inoue. He was brilliant. He wrote about Hiroshima, without fail, right up to his death.

I'm spending my later years as a writer feeling depressed. I'm afraid that I will die as someone whose writing and statements have not played a real role in the elimination of nuclear weapons. However, I have not stopped thinking about the issues raised by Hiroshima.

"Shingan no Kuni," which I read at the age of 16, pierced my heart as a point for living. It was connected to the point of Professor Watanabe at the university, to the points of Dr. Shigeto and Mr. Kanai in Hiroshima, and eventually to the point of my late friend, the critic Edward Said. I think that I myself exist as a human being surrounded by those people.

A doctor said that we would not see significant development in Hikari, my mentally-challenged son. But before we knew it, he came to express his own unique nature. He expressed this not in words, but in music. As Pascal said, human beings have "an instinct which lifts us up." I think living involves rising higher, not walking on the same plane.

The day nuclear weapons are eliminated

The end of the Cold War in the 1990s was an opportunity to eliminate nuclear weapons; instead, nuclear arms have proliferated. A new version of "Kakujidai no sozoryoku" ("Imagining the Atomic Age") was published in 2007 and a new epilogue entitled "Kagirinaku oawarini chikai michinakaba no epirogu" ("Close to the end, an epilogue half-done") was added to the series of lectures made by Mr. Oe in Tokyo in 1968. In this epilogue, he refers to the emerging danger of terrorists wielding smaller-sized nuclear weapons.

In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States, a certain peril lurking behind the nuclear regime primed by that nation, or nuclear authority if I may borrow the expression of Toshihiro Kanai, has grown. Terrorists might take advantage of such circumstances to obtain nuclear weapons, and a nuclear incident may occur.

U.S. President Barack Obama called for "a world without nuclear weapons" in a speech he made in Prague in April 2009, shortly after he assumed the presidency. Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who had been a supporter of the nuclear regime, and top officials of the British government, among others, began speaking out about nuclear abolition. All this has transpired because real politics, which seem rigid but are not, were forced into action. All those people have come to believe that nuclear weapons are no longer as effective as they once thought.

The leaders of these nations have begun thinking about "nuclear abolition" from the viewpoint of those who possess the power of nuclear weapons, not from the perspective of A-bomb survivors and their supporters, who have continued to stress that nuclear weapons bring about horrific consequences to human life. Though their starting point is different from ours, this is fine since nuclear arms, which annihilate human life, must be eliminated.

To advance the cause of nuclear abolition, Japan must completely abide by the three non-nuclear principles. Japan should enshrine the principles into law and never allow Okinawa to become a point of transit for nuclear weapons. Japan should call for the withdrawal of U.S. military forces stationed here, as a legal issue. That would lead to the nullification of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, then other treaties, including economic treaties, could be pursued. Some say that nullification of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty would impact the stability of Asia. However, stability cannot be earned in Asia if Japan tolerates U.S. nuclear weapons while perceiving the nuclear arms of other nations as a threat. A new national campaign arising from Hiroshima is needed.

Devising the means to eliminate nuclear weapons on a global basis is a difficult task. How can the inequalities felt in the world, including among the nuclear weapon states, be overcome? Can the United Nations possibly establish a rigorous mechanism to prevent nuclear arms from ever falling in the hands of terrorists? If someone says that nuclear weapons can be eliminated in 10 years, I would like to ask: "Are you sure?" I do not have sufficient courage to set a target year for nuclear abolition. However, if I said that nuclear weapons could be eliminated in 30 years, which would be nearly 100 years after the atomic bombings, I would end up insulting the potential of human beings.

Edward Said took an optimistic view of the Palestinian issue. I also maintain hope for nuclear abolition because of the human penchant for effort. I can say that I believe abolition will be realized. Living for nuclear abolition means to see the issue of the atomic bombings as a universal issue for human beings without betraying those who perished in the bombings. It also means recovering the real meaning and power of the stereotyped expression the "heart of Hiroshima."

profile

Kenzaburo Oe

Mr. Oe was born in 1935 in Ehime Prefecture. While studying French literature at the University of Tokyo in 1958, he won the Akutagawa Award for "Shiiku" ("The Catch"). In 1994, Mr. Oe was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for creating "a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today" through "Kojinteki na Taiken" ("A Personal Matter"), "Man'engan'nen no Futtoboru" ("The Silent Cry"), and "Natsukashii Toshi eno Tegami" ("Letters to My Sweet Bygone Years"), among other works. Following "Sayonara Watashi no Honyo!" ("Farewell, My Books!") and other books, Mr. Oe published "Suishi" ("Death by Water") at the end of last year, in which he, in a forest on Shikoku Island, explored the spirit of the times his father, who died at the end of World War II, was alive.

(Originally published on October 10, 2010)