Nuclear weapons can be eliminated: Special Series, Part 7

Jan. 14, 2010

Special Series: The Day the Nuclear Umbrella is Folded

Part 7: A nuclear-armed Japan is unrealistic: 8 reasons why Japan must never go nuclear

by the "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated" Reporting Team

As a result of unsettling developments in the Asian region, including two nuclear tests by North Korea and the buildup of arms in China, voices have been raised in Japan calling for the nation to become a nuclear power. These voices, though small in number, argue that Japan must establish its own nuclear deterrence capability so that it will not be forced to continue relying on the U.S. "nuclear umbrella."

The international community, however, is striving to advance nuclear disarmament, and ultimately, achieve the elimination of these weapons. The idea of developing nuclear arms is contrary to these efforts and would be an unwise decision in every respect. Such a move would also negate the call for nuclear abolition that Japan, the A-bombed nation, has been making for so long. A nuclear-armed Japan is unthinkable for a number of reasons. We would like to consider this issue from eight different angles.

Nuclear power plants would stop

Nuclear power plants, which generate 27.5% of Japan's electricity, would be forced to stop operations. If 53 nuclear reactors in Japan became defunct, industry and daily life would be seriously compromised.

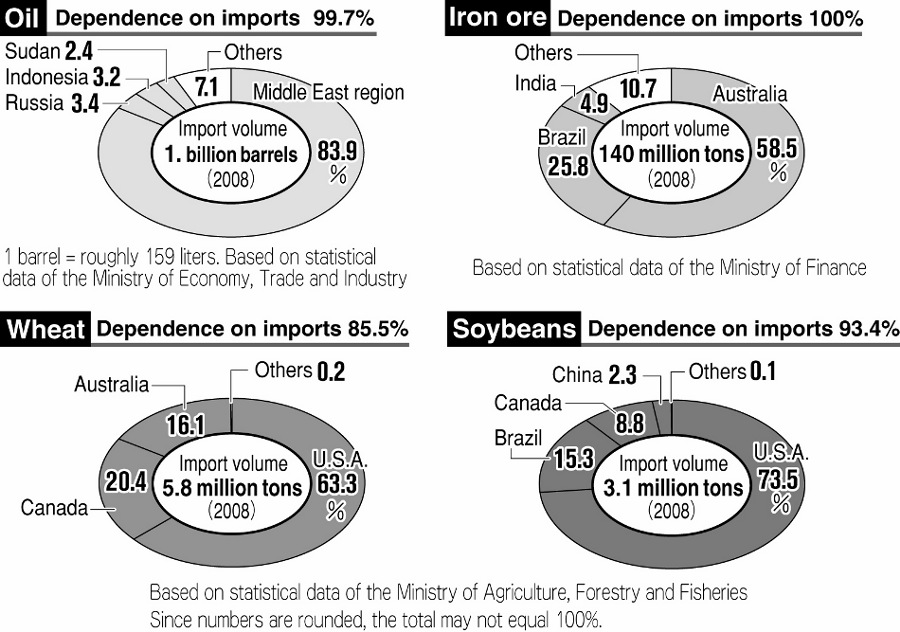

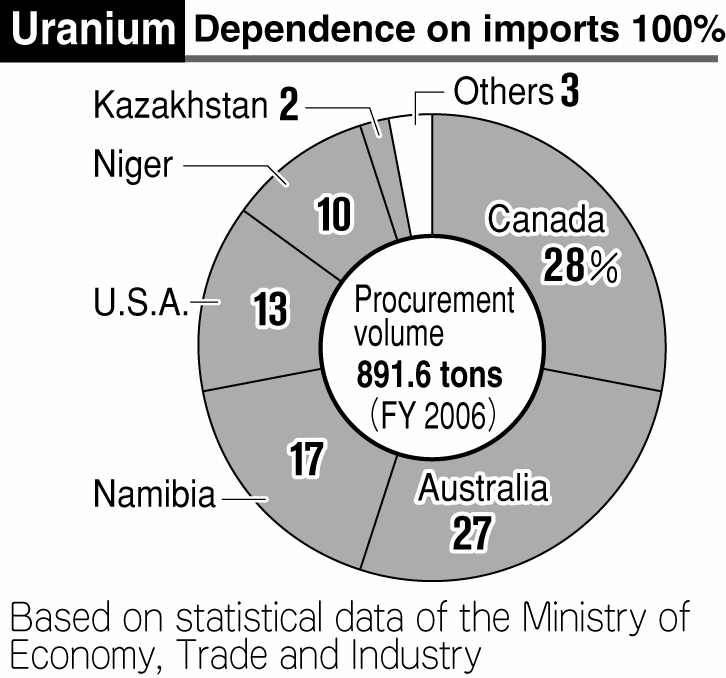

As Japan has a dearth of natural resources, it must import all the uranium needed for its nuclear power generation. Uranium, however, can also be used for nuclear weapons. Therefore the material is under the strict surveillance of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), based on the provisions of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). These safeguard mechanisms prevent uranium from being diverted for military purposes.

Nuclear cooperation agreements that have been made between Japan and the exporting nations stipulate the peaceful use of this uranium. Uranium imports will be stopped if diversion for military use is suspected.

Furthermore, the nuclear cooperation agreements with the United States, Australia and other nations specify that in the event of violation, Japan will be required to return the uranium to the exporting countries.

Japan's economy would collapse

If Japan were to pursue a nuclear arsenal, the United Nations Security Council would adopt a resolution to impose sanctions on Japan, severely restricting imports and exports. The industries that depend heavily on trade, like automobile and electronic manufacturers, would be hard hit, and the economy would collapse.

In October 2006, when North Korea announced that it had successfully conducted a nuclear test, the Security Council decided to impose sanctions including an embargo on materials that can be used for weapons of mass destruction and luxury goods as well as a freeze on financial assets related to nuclear programs. In May 2009, when North Korea conducted another nuclear test, the Security Council again adopted a resolution that imposed additional sanctions. Japan could hardly sustain the running of the nation if it became isolated from the international community. What if such sanctions were to be imposed on Japan?

"Japan's economy, which depends on importing raw materials and exporting manufactured products, would fall apart, resulting in a great depression," predicts Takuro Morinaga, an economist. He is severely critical of those who side with Japan's nuclear armament, which, he says, is a ridiculous idea that would sacrifice the living conditions of the Japanese people.

According to trade figures from the Ministry of Finance, Japan's total exports in fiscal year 2008 were valued at about 71.1 trillion yen, and that of imports was about 71.9 trillion yen. The foreign reserve was about 100 trillion yen, but the self-sufficiency ratio for food was only about 41%.

Enormous expense would be involved

Enormous expense would be required not only for developing nuclear weapons but also for creating a system to manage these weapons. This could more than double the current budget for defense.

Generally speaking, in order to be used as weapons, nuclear warheads need delivery vehicles such as missiles and military aircraft. The British government is planning to renew its fleet of nuclear submarines that carry ballistic missiles. The cost is estimated to be about 20 to 25 billion pounds (3 to 3.7 trillion yen) for renewing four submarines and missiles as well as renovating nuclear warheads. This is close to Japan's entire defense budget for fiscal 2009, which stands at 4.7 trillion yen. If Japan embarks on designing, developing and deploying nuclear warheads and delivery vehicles from scratch, the expense would be even higher.

Operational costs would also be required to keep nuclear weapons ready for actual use in warfare. According to some estimates given by private sector organizations, the accumulated cost in the case of the United Kingdom is about 76 billion pounds (11.4 trillion yen) including the cost of nuclear weapons deployed on submarines for 30 years.

A nuclear domino effect would occur in Asia

If Japan goes nuclear, this would herald the beginning of a nuclear arms race involving Asia as a whole and lead to the collapse of the NPT regime.

Kumao Kaneko, who was the first director of the Nuclear Energy Division of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and studied nuclear policies while at the ministry during the 1960s, analyzes that if Japan reaches for nuclear arms, neighboring nations will also accelerate their nuclear programs, which, in turn, will pose a greater threat to Japan. He argues that, contrary to the intention, this would undermine the pursuit of deterrence and prove nothing but damaging.

Because the NPT permits the five nuclear weapon states, including the United States, to possess nuclear weapons but bans all others from acquiring them, the treaty has been criticized as inequitable. In fact, India, Pakistan and Israel have refused to sign the NPT and gone on to acquire nuclear capability.

At the same time, the NPT has served to prevent the uncontrolled proliferation of nuclear weapons. At the beginning of the 1960s, before the NPT took effect in 1970, U.S. President John F. Kennedy reportedly expressed this concern, saying that nuclear weapons might proliferate to 15 to 20 countries by the 1970s.

Weapon-grade materials would be difficult to obtain

Nuclear materials such as uranium and plutonium, needed to manufacture nuclear weapons, are also used for power generation. According to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and other sources, as of the end of 2008, Japan had stocked about 20,000 tons of uranium in addition to about 9.7 tons of plutonium extracted from spent fuel. At the same time, Japan stores over 25 tons of additional plutonium in the United Kingdom and France.

Both are low-enriched reactor-grade materials. To enable these materials to efficiently yield the type of enormous energy needed in small nuclear warheads, various measures, including enriching the uranium and plutonium to over 90%, or "weapon-grade," must be undertaken.

However, with the safeguards put in place by the IAEA, enriching these materials would be difficult. Cameras installed in nuclear facilities monitor the activities there, and about 80 IAEA inspectors have their eyes on Asia.

Uranium mines located in the prefectures of Tottori and Gifu currently produce no uranium. Kinji Koyama, a research fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, who once worked at the IAEA, states, "I can assure you that Japan has no access to free nuclear material."

The knowhow is lacking

During World War II, Japan conducted research on developing atomic bombs--the Army at the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research and the Navy at Kyoto Imperial University (today's Kyoto University)--but both failed to start production. Today, with its advanced science, Japan is said to have the technical capability to develop nuclear weapons. However, actually producing such a weapon requires detailed knowhow and this would take considerable time.

Katsuya Yamada, a professor of theoretical physics at Los Angeles Pierce College, estimated in his book titled Can Japan Make an Atomic Bomb? that it would take at least five years for Japan to develop nuclear weapons even if a large budget, excellent human resources and abundant materials are provided.

Professor Yamada stressed, "The world knows well that Japan is the only A-bombed nation. Conscientious, peace-loving people would be terribly dismayed if Japan develops nuclear weapons. It would be an utter disgrace."

Although Japan has scientists and engineers versed in the field of nuclear weapons, it is unlikely many of these people would want to participate in the actual work of developing such weapons.

No location for nuclear tests

Even if Japan built a nuclear bomb, it could not verify the bomb's efficacy without testing it. And it would not be until the world heard the news that "Japan conducted a successful nuclear test" that the nation could claim to hold a nuclear deterrent with regard to its neighbors. As such a small country, though, where could Japan conduct this nuclear test?

Large nations like the United States and China can conduct nuclear tests within their own borders. Russia repeatedly carried out nuclear tests in Kazakhstan, which used to be a part of the former Soviet Union. Meanwhile, France and the United Kingdom conducted their nuclear tests in Algeria and Australia, respectively, and at other sites in the Pacific Ocean far removed from their home territory.

Perhaps Japan could perform a nuclear test on some deserted island, but its impact on the environment and the fishing industry could lead to reparation issues. In addition, Japan has already ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Though the treaty has not yet entered into force, Japan would be forced to rescind its ratification after the test.

And if Japan sought to conduct a subcritical nuclear test, which some say is not banned by the CTBT, opposition to such a move would surely be expressed by residents near the test site as well as others throughout the nation.

Public opinion will never permit Japan's nuclear armament

Japan's nuclear armament will never be permitted by the people of Japan, including those who live in the A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which have been appealing for nuclear abolition. A nationwide protest would break out, in line with the long history of the anti-nuclear and peace movement in Japan.

In 1954, the crew members of a Japanese fishing boat called the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) were exposed to the nuclear fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. This incident stirred a spirited campaign against nuclear weapons, which spread rapidly across Japan. This strong public opinion opposed to the nation's nuclear armament was also a driving force in making Japan's three non-nuclear principles--not possessing, not producing and not permitting nuclear weapons into Japanese territory--a national credo.

The City of Hiroshima has issued a letter of protest every time a nuclear test has been conducted somewhere in the world. A-bomb survivors and the citizens of Hiroshima have repeatedly held sit-ins in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims to express their opposition to nuclear arms and to appeal for peace. The voices of Hiroshima were a contributing factor in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issuing its advisory opinion in 1996, ruling that "the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law."

In this regard, Motofumi Asai, President of the Hiroshima Peace Institute of the Hiroshima City University, says, "If we become used to the government's policy of relying on the nuclear umbrella while advocating the three non-nuclear principles, people will become less conscious of the need to oppose nuclear weapons. Japanese citizens must stand firm to correct this contradiction on the part of the government."

No-nukes is the wisest policy

Japan, the A-bombed country, has contemplated the possibility of going nuclear since the end of World War II. In the debate over signing the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), some contended that the nuclear option should remain open. Japan joined the NPT six years after the treaty had come into effect in 1970, but even at that time, the Cabinet Research Office (currently, the Cabinet Intelligence and Research Office) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) discussed the possibility of possessing nuclear weapons.

Due to these and other factors, including Japan's lukewarm support for the indefinite and unconditional extension of the NPT at the 1993 G7 summit meeting in Tokyo and the large stockpile of plutonium the nation has acquired, the world holds suspicions that Japan might pursue the development of nuclear arms.

However, for the "eight reasons" outlined above, going nuclear isn't a plausible path for Japan to take. There are a variety of laws and treaties which also constrain this course of action as well as Japan's moral position as the world's only nation to have suffered nuclear attack. Some argue that Japan's constitution should be amended to enable it to possess such weapons. Presently, Article 9 of the constitution, based on the government's interpretation, stipulates that Japan can only possess a minimal arsenal for self-defense, preventing the acquisition of weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

Meanwhile, others have recently argued that Japan should "share nuclear weapons" with the United States rather than building a bomb of its own. Under such a system, nuclear weapons would be managed by the United States at U.S. bases in Japan and Japan would have access to these arms in the event of an emergency. This argument is based on the fact that the United States has placed strategic nuclear weapons on soil of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) nations.

Similarly, Japan could share a "nuclear button" with the United States with regard to U.S. strategic nuclear submarines.

These ideas, however, would be nothing but an unnecessary provocation to Japan's neighbors. Paul Ingram, an expert on regional security in the United Kingdom, commented from the standpoint of preventing nuclear proliferation, saying, "The idea of putting nuclear weapons in a nonnuclear state and using the weapons in the event of an emergency would undermine confidence in the NPT and be subject to worldwide criticism."

Japan should announce with pride, both at home and abroad, that the nation has no intention of going nuclear and it should make every effort to extricate itself from the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Surely this would be the wisest course of action for Japan, as the world's only nuclear-bombed nation, to pursue.

Keywords

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

IAEA was established in 1957 to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology. Its headquarters is located in Vienna, Austria. It is also called the "nuclear watchdog," and now has 151 member countries. Yukiya Amano took office as the first Japanese Director General of the IAEA in December 2009. In 1977, Japan concluded a safeguard agreement with the IAEA. In 1998, Japan signed an Additional Protocol under which the scope of verification by the IAEA was expanded to civilian facilities. As there was no indication of the diversion of nuclear material for military purpose, the Integrated Safeguards (IS) Scheme with reduced verification requirements has been implemented in Japan since 2004.

Uranium and Plutonium

Plutonium is extracted from the spent fuel after uranium is burned in a nuclear reactor. Uranium is enriched to 3~5% for power generation while it must be enriched to over 90% for nuclear weapons. Japan holds one of the largest stockpiles of plutonium, including over 25 tons stored in the U.K. and France.

(Originally published on January 3, 2010)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.