Nuclear weapons can be eliminated: Special Series, Part 8

Jan. 19, 2010

Special Series: The Day the Nuclear Umbrella is Folded

Part 8: On the 50th anniversary of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty

by the "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated" Reporting Team

The year 2010 marks the 50th anniversary of the revised Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. Since last year, Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama has said that he and U.S. President Barack Obama are in agreement with regard to deepening the Japan-U.S. alliance and Mr. Hatoyama expressed the hope that Japan would pursue "an equal relationship" with the United States and that "Japan-U.S. relations would be reviewed."

How, then, should Japan, the only nation to have suffered nuclear attack, refashion its relationship with the United States, the country which dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Are the U.S. bases in Japan and the U.S. "nuclear umbrella" truly needed?

Change seen in Japan-U.S. security relationship

At the end of last year, U.S. Embassy Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM) James Zumwalt spoke on the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty at the Defense Issues Seminar held in Fukuoka.

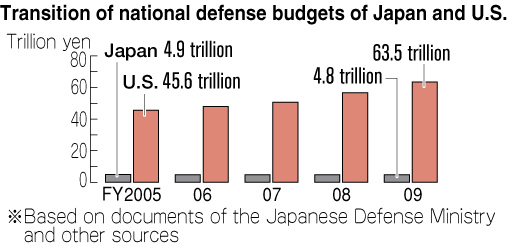

Speaking about this figure projected on a screen, Mr. Zumwalt stressed the benefits to Japan of the Japan-U.S. alliance. The cost of constructing an Aegis ship is $1.2 billion dollars and nearly $5 billion dollars for a George Washington class aircraft carrier. The U.S. has footed this bill and deployed a total of nearly 50,000 troops both in Japan and at sea near Japan.

Mr. Zumwalt summarized the change that has taken place over the past 50 years since the revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty by saying, "Japan was once defended by the United States. Currently, Japan and the United States are working together to protect Japan."

A typical example of this, he pointed out, is Missile Defense (MD).

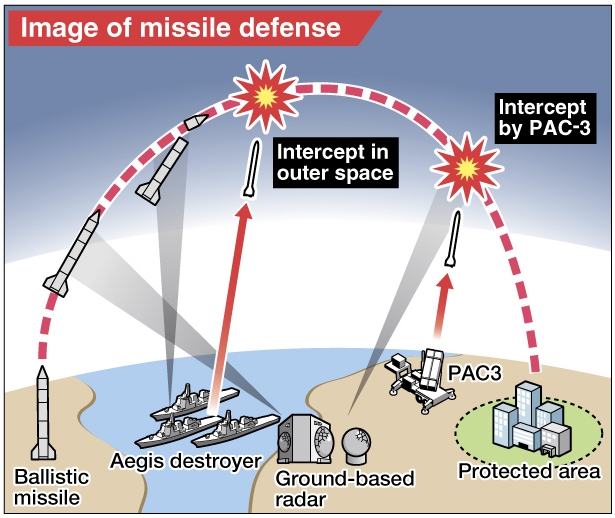

The MD system employs two stages. When radar detects a missile from an enemy nation, the Aegis maintained by the Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) will launch a Standard Missile-3 interceptor (SM-3) and destroy the missile in space. If the strike does not destroy the missile, a Patriot PAC-3 from the Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) will shoot it down.

Both SM-3 and PAC-3 interceptors were jointly developed by Japan and the United States. The two nations also work together in operating the missiles, including sharing the data obtained by radar.

The Japanese government has endorsed basic policy guidelines in regard to compiling the defense-related budget for FY2010. The new budget plan includes an increase in the number of PAC-3 interceptors, which are currently deployed at the 12 ASDF bases, to 16.

The Aegis ships "Kongo" and "Chokai" are outfitted with SM-3 interceptors. The Aegis ship "Myoko" is slated to be equipped with the interceptor, too.

Commenting on the MD system, Mr. Zumwalt said, "We have developed a very robust defense system, which includes U.S. military equipment. When a missile was launched by North Korea last year, the United States and Japan were able to demonstrate their strong alliance."

The revised U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, which was signed by the two countries on January 19, 1960, stipulates that the United States will defend Japan if it is attacked. Half a century has passed since then. The current Japan-U.S. military alliance has evolved into a new partnership. Now, the mutual defense by the two nations in the event of contingencies in Japan is discussed in the context of the Asia-Pacific region and Japan provides logistical support for U.S. troops dispatched to the Middle East.

During this time, Japan has increased its spending on U.S. forces stationed in Japan, known as host nation support, and expanded the scope of its logistical support by the SDF as well as its international contribution, including the refueling of naval vessels deployed by multilateral forces conducting operations in Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, no national consensus has been reached on the scale of U.S. forces in Japan and on their necessity. Nor can it be said that sufficient discussion has been made over the dispatching of U.S. troops in Japan to various countries in the world for military operations. Not only would the development of an MD system require enormous expense, if missiles aimed at the United States are intercepted by Japan, there would be concern that this amounts to a violation of the constitution, which forbids the right to collective self-defense. In addition, the fact remains that the U.S. facilities are highly concentrated in Okinawa.

Prime Minister Hatoyama's vision for security

How can the Hatoyama administration, now in disarray due to the dispute involving the Futenma U.S. Airbase located in Ginowan, Okinawa Prefecture, deepen the Japan-U.S. cooperation? In the past, Mr. Hatoyama has argued for a security alliance with the United States that does not have to depend on U.S. forces being stationed in Japan.

Kazumi Mizumoto, an associate professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University said, stressing the importance of national debate over the future of general relations between the two countries, "Japan-U.S. relations should come first and the military alliance should be included in this relationship." Mr. Mizumoto believes that, in order to deepen the relationship between Japan and the United States, "it would be better to speak openly of not needing nuclear weapons for the nation's defense rather than trying to impose restrictions on their use."

U.S. personnel stationed in Japan

Army: 2729

Navy: 5940

Air Force: 12,350

Marines: 16,640

Total 1: 37,659

Seventh Fleet Force (deployed at sea): 11,283

Total 2: 48,942

DOD-related employees: 5252

Family members: 43,093

Total 3: 97,287

Japanese employees: 25,499

Interview with Hirofumi Tosaki at the Japan Institute of International Affairs

Hirofumi Tosaki, resident senior fellow of the Center for the Promotion of Disarmament and Non-proliferation and an expert on the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, sat down with us to speak about an appropriate security arrangement. Below are Mr. Tosaki's profile and his comments.

Hirofumi Tosaki

Mr. Tosaki was born in Kagoshima in 1971. He earned a Ph.D. from Osaka University. He has been in his current post since 2007. He specializes in arms control and missile defense issues.

Japan's exclusively defensive security policy poses no threat

With the collapse of the Cold War paradigm, the threat from the former Soviet Union disappeared. In Asia, however, there are still sources of tension, including North Korea's nuclear armament and the military buildup in China. As a result of this change in circumstance, Japan has called for a new defense capability when it comes to MD, dealing with terrorism and guerrilla attacks, and defending its islands. This capability, however, has not yet been achieved.

Compared with that of North Korea, Japan's military equipment is more modern. Japan has upheld an exclusively defense-oriented policy and has not acquired military equipment, such as ballistic missiles and bombers, that could attack the territory of other countries. In this sense, Japan's military capability--excluding that of the U.S. forces stationed in Japan--cannot be considered a threat for China and North Korea. Those nations, though, would be sensitive to a significant shift in Japan's security policy, like pursuing the development of nuclear weapons.

Maintaining a no-nukes policy

Of course, it is important for Japan, with the experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to maintain a no-nukes policy. If Japan should reverse this policy, its credibility in the world built up over the years would collapse and the world's efforts to promote disarmament would be severely undermined.

What we have to be careful about is assuming that a "nuclear-free world" equals a "peaceful world." We must not forget that a nuclear-free world, where no nuclear deterrent exists, might actually increase the possibility of more conflicts using conventional weapons.

We cannot deny that the nuclear deterrent capability of the United States was effective in maintaining some stability in the world and preventing conflicts to a certain extent during the Cold War era and in Northeast Asia after the Cold War ended. First, we should recognize this fact. Then, we should make our starting point the consideration of actions for the new era.

Gradual but steady reduction

Suppose if Japan declares that "nuclear weapons are not needed to defend Japan." Under the current Japan-U.S. alliance, what would happen? Would North Korea and China find this credible? The United States might view this as interference with the way it defends Japan. If the Japan-U.S. alliance is still vital to the security of Japan, getting out from under the "nuclear umbrella" is not yet a practical idea.

We should do our best to make the region safe without any reliance on nuclear weapons. It is important for the whole region to decrease its dependence on military might. At the same time, we should work hard to reduce nuclear weapons gradually but steadily. Making these two efforts concurrently would be the wise course to pursue.

Keywords

Revision and redefinition of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty

A revision of the former Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, first adopted in September 1951, was made and signed in January 1960 and came into effect in June 1960. The new Japan-U.S. Security Treaty consists of 10 articles. Like the former treaty, the current treaty permits the U.S. presence in Japan and stipulates that the United States contribute to the security of Japan. Words such as nuclear weapons, nuclear deterrent and "nuclear umbrella" are not included in the articles.

In the Japan-U.S. Joint Declaration on Security Alliance for the 21st Century issued in April 1996, the two countries redefined their alliance, where not only Japan's security but also the "peace and security in the Asia-Pacific region" are considered, to adjust to the post-Cold War landscape of the world. On this basis, the "Law Relating to Measures for Preserving the Peace and Security of Japan in the Event of a Situation in the Areas Surrounding Japan" was passed in May 1999, and the framework, where the SDF provides the United States with logistical support, was formed.

(Originally published on January 10, 2010)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.