Nuclear weapons can be eliminated: Special Series, Part 11

Feb. 7, 2010

Special Series: The Day the Nuclear Umbrella is Folded

Part 11: Effective nuclear weapon-free zone treaty a path to security

by the "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated" Reporting Team

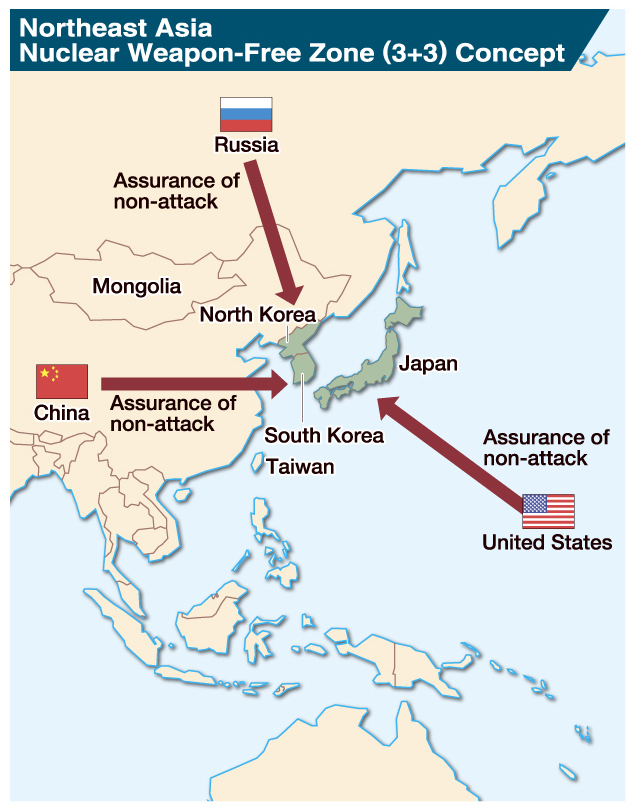

A treaty is one way to create a security framework in Northeast Asia that is not dependent on nuclear weapons. Under such an agreement the nations in the region renounce the development and deployment of nuclear weapons and seek a pledge from the nuclear nations not to launch a nuclear attack against them.

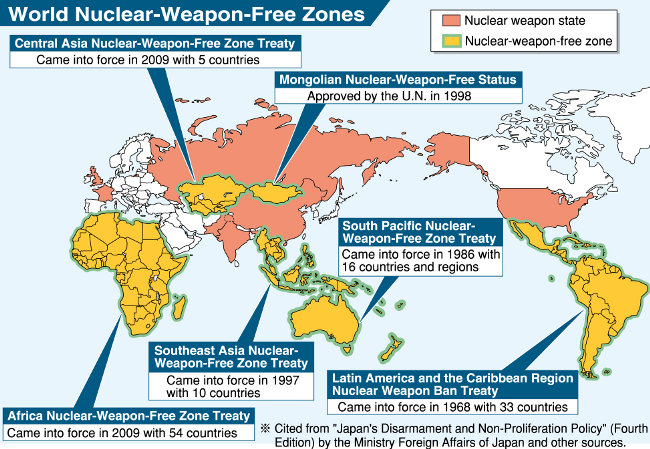

To date, there are five such treaties in the world, including one covering five countries in central Asia and another covering 54 countries in Africa. When Mongolia, whose declaration of non-nuclear status has been approved by the United Nations, is included, a total of 119 nations and regions are under this "non-nuclear umbrella."

Before a nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia can be created, several difficult issues must be resolved, including North Korea’s nuclear development and the U.S. nuclear umbrella over Japan and South Korea. The wisdom and know-how to draft a more effective treaty is needed.

Explore possibilities at legislator level

"The creation of a nuclear weapon-free zone based on a treaty is the path to a new guarantee of security," said Kumao Kaneko, 73, a foreign affairs analyst and former director of the Foreign Ministry’s Nuclear Energy Division. In 1996 a concept he had been working on since the 1970s was published in a U.S. journal. Mr. Kaneko has continued to advocate a nuclear weapon-free zone for Northeast Asia.

When China conducted a nuclear test in 1964, many in Japan came to believe that China posed a threat to the nation, and some advocated Japan's nuclear armament. But Japan elected to rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella rather than acquire its own nuclear weapons. Meanwhile North Korea has moved forward with nuclear development, and the nuclear threat remains in Northeast Asia.

"If we don't get out of the cold war mentality, this vicious cycle will continue in Northeast Asia," Mr. Kaneko said. "If North Korea's fears are not allayed, nuclear disarmament will be difficult." Not only must the nations of the region pledge to renounce nuclear weapons, but by including nuclear nations in the treaty, Negative Security Assurance that precludes nuclear attacks and threats against non-nuclear nations can be made legally binding. This would lead to an even safer region.

Since the 1960s, when there was a heightened risk of nuclear war, agreements have been reached on nuclear weapon-free zones, and five treaties have come into force. But neither the U.S. nor the four other nuclear nations have readily made a pledge of Negative Security Assurance. Complete agreement has been reached only in the Latin American and Caribbean region. Mr. Kaneko's proposal attempted to enhance the effectiveness of such treaties by including the nuclear nations in the discussions from the start.

Like Mr. Kaneko, Hiromichi Umebayashi, 72, special adviser to the non-governmental organization Peace Depot, is another strong advocate of a nuclear weapon-free zone, from the private sector. "Northeast Asia, which includes the A-bombed nation of Japan, must learn from similar systems around the world and create a system appropriate for the conditions in this region," he said.

Mr. Umebayashi cited the example of Australia's double standard. While Australia is a signatory of the South Pacific Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty, it remains under the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

In the draft of a model treaty he published in 2004 Mr. Umebayashi included provisions for the abandonment of the nuclear umbrella. "I'm not saying we should scrap the security agreement between Japan and the U.S.," Mr. Umebayashi said. "But we have to demonstrate that we will not rely on nuclear weapons in creating a nuclear weapon-free zone."

How to take this approach to the policy level is the challenge now facing the new administration led by the Democratic Party of Japan.

In 2008 the DPJ Parliamentarians for Disarmament Promotion published a draft treaty whose content was nearly the same as that proposed by Mr. Umebayashi. In the party manifesto promoted during last summer's House of Representatives election, the DPJ did not directly address the issue of a nuclear-free zone but said it would "seek the denuclearization of Northeast Asia."

Hideo Hiraoka, a member of the House of Representatives from Yamaguchi Prefecture, serves as director of the group of parliamentarians who are promoting nuclear disarmament. "There has not been enough debate within the government," he said. "But if possible I would like to pursue denuclearization with the support of politicians from all parties." Last November Mr. Hiraoka and the members of Peace Depot visited South Korea where they met with a group that included legislators from the National Assembly. South Korean lawmakers are scheduled to come to Japan in late February. Mr. Hiraoka said he first wants to enhance friendship and debate at the legislator level before expanding the discussions to include North Korea.

The Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference will be held in May. Representatives of nations in nuclear weapon-free zones around the world will gather at an international conference scheduled to be held in New York just prior to the review conference. Mr. Umebayashi will serve as coordinator for the legislators from Japan and South Korea. "I'm trying to see if we can arrange for the lawmakers from the two countries to issue a statement," he said. "The support of the nations of the world is essential if we are to create a nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia."

Proposals for the Creation of a Nuclear Weapon-free Zone in Northeast Asia

Proposal: "Three plus three" approach

Proposed by: Hiromichi Umebayashi, 1996 (draft of model treaty published in 2004)

Proposal: Circle with a radius of about 2,000 km centered on Panmunjom

Proposed by: Kumao Kaneko, 1996

Proposal: Region encompassing Japan, South Korea, North Korea and Taiwan

Proposed by: Andrew Mack (Australia), 1995

Proposal: Circle with a radius of about 2,000 km centered on Panmunjom (later changed to an oval including part of Alaska) (limited to tactical nuclear weapons)

Proposed by: John Endicott (U.S.), 1995

Interview with Tsutomu Ishiguri, professor at Kyoto University of Foreign Studies: How to build a consensus between nations

While working for the United Nations, Tsutomu Ishiguri, a professor at Kyoto University of Foreign Studies, contributed greatly to the creation of the Central Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty by serving as a coordinator between nations. Based on his experiences, the Chugoku Shimbun asked him about how to build a consensus and the problems that will be faced. Below are Mr. Ishiguri's profile and his comments.

Tsutomu Ishiguri

Mr. Ishiguri was born in Niigata in 1948. A graduate of Waseda University, he joined the Foreign Ministry in 1972. He moved to the U.N. Department of Disarmament Affairs in 1987 and served as director of the United Nations Regional Center for Peace and Disarmament in Asia and the Pacific from 1992 through March 2008. He assumed his current post the following month.

Addressing issues while developing an approach

In order to create a nuclear weapon-free zone, all of the nations that comprise the region must be non-nuclear nations. That is the basic premise. In the case of Northeast Asia, there will be no way to achieve this goal without the denuclearization of North Korea. And reaching a consensus among the governments of the nations involved once that is accomplished will not happen overnight. A rocky road lies ahead.

But if nothing is done, no progress can be made. The six-party talks that are working toward the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula are a dialogue between governments, so the countries involved continue to butt heads and the talks remain bogged down. I suggest creating another complementary channel for dialogue where regional issues, including North Korea's disarmament, can be addressed and resolved. This may allow us to make a fresh start.

A quasi-governmental conference would be preferable for that channel of dialogue because with the private sector alone it would be difficult to tie the results to government policy. Take, for example, the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP), which was created after the end of the Cold War. It includes the United States as well as the countries of Asia. I propose holding dialogues between government officials and researchers from the various nations centered on CSCAP.

Enhanced security is a major fundamental principle when embarking on the formulation of a new security framework. Nothing will change unless nations share an awareness of the fact that the creation of a region whose security is not reliant on nuclear weapons will lead to enhanced security and peace. Considering the future of Northeast Asia through a low-key, quasi-governmental dialogue may ultimately provide a shortcut to forming a consensus among the nations.

Understanding on the part of nuclear nations crucial

Negotiations to encourage action on the part of the nuclear nations of the United States, Russia and China are also necessary. Looking at the current situation, North Korea blames the hostile policy of the United States for its refusal to eliminate its nuclear weapons. The presence of a nuclear nation in the vicinity will also present an obstacle to any effort by Japan and South Korea to get out from under the nuclear umbrella.

North Korea's denuclearization will be affected by whether or not the United States and other nuclear nations can pledge to respect national sovereignty and inviolability, including Negative Security Assurance under which they agree not to launch a nuclear attack on non-nuclear nations.

A nuclear weapon-free zone will help prevent conflicts in the region as well as contribute to nuclear non-proliferation. We must remind the nuclear nations as well of those benefits.

Building trust through easing of tensions

But a nuclear weapon-free zone is not the ultimate goal of security. If there is an overwhelmingly powerful conventional military, a threat exists. Some have cited the expansion of China's military and the modernization of its weapons, and there is no clear picture regarding the state of North Korea's chemical and other weapons.

If we do not create an environment under which information is shared and the lack of a mutual threat can be verified, mutual trust cannot be fostered. A path to the creation of a nuclear weapon-free zone must be sought when debating the overall easing of tensions in Northeast Asia.

(Originally published Jan. 31, 2010)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.