International symposium in Hiroshima urges trust-building role for A-bombed cities

Aug. 7, 2012

On July 28, an international symposium was held at the International Conference Center Hiroshima to explore the possibility of a nuclear-free Northeast Asia, which has continued to suffer from tensions even after the end of the Cold War. Titled “Promoting a Nuclear-Free Northeast Asia: The Pursuit of a Nuclear-Free World from Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” the symposium was sponsored by Hiroshima City University, the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition at Nagasaki University, and the Chugoku Shimbun. Taking into account conditions in the world and in the nations involved, experts from Japan and abroad discussed such issues as the current challenges of this aim, Japan’s role as the A-bombed nation, and the consequences of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Below are excerpts from the discussion.

Panelists

Sergio Duarte, Former High Representative, United Nations for Disarmament Affairs

Hiromichi Umebayashi, Director, Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University

Cheon Seongwhun, Senior Research Fellow, Korea Institute for National Unification (South Korea)

Hisako Iizuka, Researcher on Contemporary Chinese Political Issues

Yumi Kanazaki, Editorial Writer, The Chugoku Shimbun

Presenter

Keisaburo Toyonaga, Director of Hiroshima Branch, Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims

Moderator

Kazumi Mizumoto, Vice-President, Hiroshima Peace Institute, Hiroshima City University

Ms. Iizuka: A stable region benefits China as well.

Mr. Duarte: In Central and South America, nations have changed their policies to emphasize dialogue.

Mizumoto: Separately from Mr. Umebayashi, Mr. Cheon has also proposed the denuclearization of Northeast Asia.

Cheon: In 2000, together with a Japanese researcher, I issued a proposal called the Trilateral Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (TNWFZ) in Northeast Asia with Japan, South Korea, and North Korea as the participating countries. The rationale behind this vision includes stemming North Korea’s atempts to go nuclear and ridding international suspicions over South Korea’s and Japan’s nuclear intentions, among other objectives.

However, the vision is hindered by North Korea’s nuclear development program. For instance, although North Korea had continued to deny it was pursuing such a program, contending that it had no nuclear capability or intention, the existence of its uranium enrichment facility surfaced in 2010.

Iizuka: China has strengthened its standing in the world since it first began building a nuclear arsenal in 1964. For China, its nuclear weapons are a symbol of “patriotism,” and serve as an anchor for uniting the nation.

Stability in Northeast Asia is absolutely crucial for China. In this sense it benefits China, too, if the international community presses North Korea to renounce nuclear weapons in order to promote the denuclearization of the region.

Duarte: A global model for a nuclear weapon-free zone treaty exists in Central and South America. But it faced challenges in the past. Brazil and Argentina, major regional powers, did not join the treaty until the 1990s. Both nations had been maintaining their nuclear development programs under military regimes, making them rivals. But when there was a change of administration in the two nations, their policies shifted to an emphasis on dialogue. The two nations built a relationship of mutual trust by undertaking such measures as establishing an organization to mutually inspect their civilian use of nuclear power, leading both countries to join the treaty in 1995.

Mizumoto: Countries in Central and South America succeeded in building a relationship of trust. Is it possible to achieve this in Northeast Asia?

Cheon: As the issue of North Korea’s nuclear development program clearly shows, they have shaken hands and worn smiles, while doing exactly the opposite behind the scenes. North Korea has deceived the international community. We must not forget its two faces.

Iizuka: It’s important to consider the denuclearization of the Northeast Asian region as one component of the total elimination of nuclear weapons from the earth. It’s essential to build trust as denuclearization is pursued.

Umebayashi: I see normalizing relations between Japan and North Korea as an important element in a comprehensive approach toward denuclearization. There is concern that the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and other security arrangements might stand in the way, yet the role played by military alliances will grow smaller as the region rids itself of nuclear arms.

Kanazaki: We must be more aware of multilayered approaches, such as increasing the number of nuclear weapon-free zones and seeking the early start of negotiations on a Nuclear Weapons Convention for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference to be held in 2015, which remains the most important framework for multinational nuclear disarmament.

Mr. Cheon: It has led to an erosion of trust in nuclear power.

Ms. Kanazaki: Media coverage on the nuclear accident must have a multifaceted perspective.

Mizumoto: What changes have occurred since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant?

Duarte: The United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) have conferred over the response of the international community to the question of nuclear energy. They have concluded that each nation must decide its own policy. Despite the disaster in Fukushima, almost every nation that uses nuclear energy has continued to operate their nuclear power stations.

Iizuka: Campaigns against the construction of nuclear power plants have emerged in the inland areas of China, but they have not spread into a larger movement. The Chinese government is continuing to promote the construction of these plants. As for nuclear weapons, the government holds the view that possessing nuclear weapons gives China a greater voice in international affairs. Unless the United States abandons its own nuclear arsenal, China will continue to possess them.

Cheon: Even for South Korea, the accident at Fukushima was a great shock. An opinion poll conducted after the disaster showed that support for the use of nuclear energy fell to less than half of what it was prior to the accident. The peoples’ trust in nuclear power has deteriorated significantly.

Kanazaki: Atomic bombs aren’t the only things that produce radiation damage. We were aware of this, yet we weren’t sufficiently conscious of the danger. Among the non-nuclear weapon states, Japan is the only nation which extracts plutonium through the reprocessing of its spent nuclear fuel. It has amassed 45 tons of plutonium, equivalent to over 5,000 Nagasaki-type atomic bombs. As a journalist of a newspaper located in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, I would like to focus on the issue of nuclear power plants from a multifaceted perspective, while holding to the position of seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Umebayashi: The biggest problem involving the use of nuclear power plants is the fact that we don’t have a way of disposing of the radioactive waste. Under these conditions, it’s only natural that we would choose not to build new plants, or at least hold off on building new plants until a method has been found to deal with the waste. If we’re unable to find a solution, we have to stop building nuclear plants.

Mr. Umebayashi: Japan must speak out in the international arena.

Mizumoto: What do you see as the role of the A-bombed nation of Japan?

Cheon: In June, Japan revised its Atomic Energy Basic Act, adding one phrase which indicates that nuclear energy should also have the objective of contributing to “national security.” Because of this move, I can’t help feeling some concern that this might open up a path toward Japan arming itself with nuclear weapons. Don’t these words contradict Japan’s three nonnuclear principles?

This revision to the law was not made with the consensus of the Japanese people. From this point forward, it will be important to watch the discourse in Japan carefully. The world has suspicions as to whether Japan’s three nonnuclear principles may be reversed.

Iizuka: There is a mutual sense of distrust between China and Japan. In China, people believe that Japan is equipped with the technology to make nuclear weapons and missiles if it chooses to do so. As for the revision of the Atomic Energy Basic Act, China has not criticized Japan for this move, but Chinese media has published articles in which South Korea is sharply critical. People in China may feel that their suspicions have been borne out. In this way the revision has widened the breach between the two nations.

Kanazaki: The activities pursued by Mr. Toyonaga and others can build trust. It’s important that all of us in Hiroshima consider what we can do, as individuals, for the denuclearization of Northeast Asia. The governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can hold humane discussions only if they listen with empathy to the accounts shared by A-bomb survivors.

Umebayashi: In April of this year, Katsuya Okada, the deputy prime minister of Japan, said in a statement at the Diet: “A nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia would be an effective means of getting North Korea to abandon its nuclear ambitions.” It’s a significant remark that has pushed the position of the Japanese government in this direction. Gaining some momentum from Mr. Okada’s comment, we must begin discussions on this issue. To put discussions of a nuclear weapon-free zone on the international agenda, the nations involved must initiate the process. The A-bombed nation of Japan must speak out proactively in the international arena.

Duarte: Hiroshima and Nagasaki hold memories of the horror of nuclear weapons. The same horror must not be repeated. To realize the abolition of nuclear weapons, Hiroshima and Nagasaki have an important role to play. My hope is that, with your unyielding spirit, you will make significant contributions toward creating a nuclear-free world.

Mizumoto: With tensions continuing in Northeast Asia, making repeated calls for denuclearization can help build trust among the people of this region.

Keynote Speeches

Sergio Duarte

Lessons of Latin American countries

In 1958, Costa Rica presented a draft resolution to the Council of the Organization of American States proposing the establishment of a nuclear weapon free zone in Latin America. Just weeks before the Cuban missile crisis, in 1962, Brazil introduced a resolution in the United Nations General Assembly with a similar goal. Although the Cuban missile crisis did not trigger action, it did serve to heighten the focus of public attention on the desirability of pursuing this project in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 1963, the Presidents of Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Mexico signed a Declaration setting forth the process that led to the negotiation and signature of the Tlatelolco Treaty only four years later.

I would like to point out in this context that Latin American States share a common Iberian heritage which is also an important part of the Caribbean history and experience. That element was obviously instrumental in garnering support for the Treaty. Moreover, our region can easily be described as the most peaceful in the world and our tradition of mutual respect and cooperation for economic and social development is certainly another factor that made the Tlatelolco Treaty possible in the uncertain times of the 1960’s.

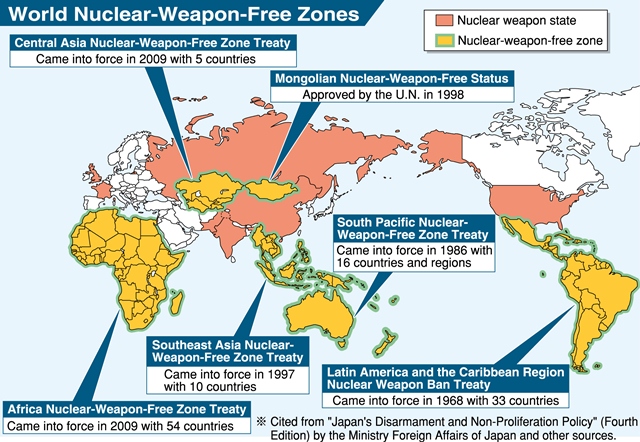

The Treaty of Tlatelolco pioneered a model that would later inspire the creation of four other zones and the proposals for the Middle East and for Northeast Asia. When these two are realized, almost all inhabited areas of the Southern Hemisphere and a significant part of the Northern Hemisphere will be free of nuclear armaments. Maybe then the existing nuclear armed States and some of their allies will at long last take a hard look on their own policies and beliefs and join the rest of the world in doing away with nuclear arms forever.

Several States today continue to rely on nuclear weapons for their security. They still claim that the use of such weapons is legal and that they must be kept because they are supposed to be militarily effective in deterring aggression. Some claim that they provide an “insurance policy” and others pay lip service to nuclear disarmament, insisting that their weapons will be kept “as long as nuclear weapons exist”, which seems to be a convenient recipe for never relinquishing them.

I must emphasize here that security is not an exclusive requirement for powerful States. All States are entitled to it and nuclear weapon free zones should enhance everyone’s security.

We all recognize the distinctive features of the political and security realities in Northeast Asia and the obstacles that stand in the way. The experience of Tlatelolco, or for that matter that of the other regions which successfully established nuclear weapon free zones, cannot be transplanted elsewhere. Nuclear weapon free zones are indeed a very effective measure of non-proliferation. To truly make a difference in today’s world, however, they must be more than that: they must represent a concrete and meaningful step towards nuclear disarmament. I sincerely wish that with patience, realism and constructive spirit, the countries in this region will achieve that objective in a not too distant future.

The whole text of the keynote speech is here.

Hiromichi Umebayashi

A Good Opportunity for Discussing Denuclearization

Efforts aimed at creating a nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia have evolved from merely discussing its feasibility or its framework to the actual means of achieving this goal.

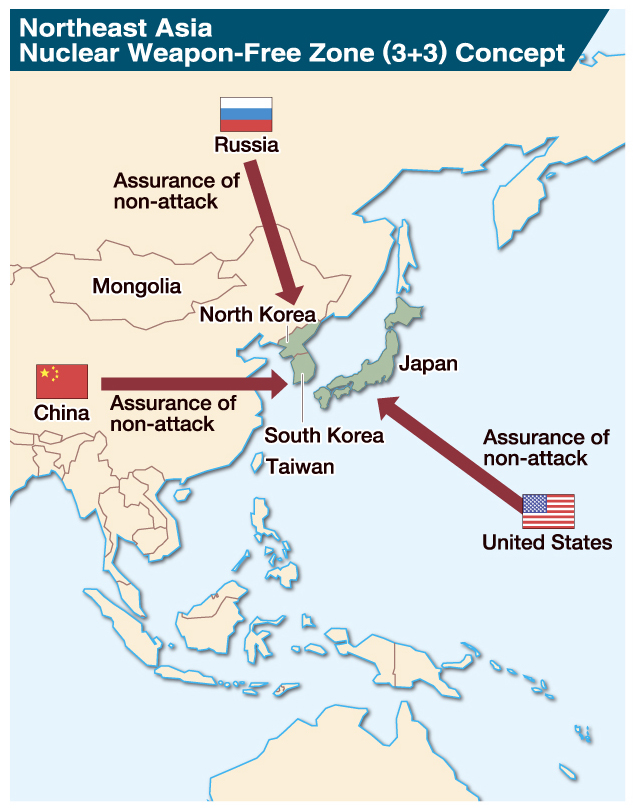

In 1996, I proposed the “three-plus-three vision.” This proposal envisions creating a nuclear weapon-free zone comprised of Japan, South Korea, and North Korea. At the same time, the nuclear weapon states in the region, namely the United States, China, and Russia, would pledge not to attack or threaten these nations with nuclear weapons. The objectives of this idea included discouraging a nuclear arms race, encouraging Japan and South Korea to leave the U.S. “nuclear umbrella,” and advancing the larger goal of eliminating nuclear weapons entirely.

Then came the framework known as the six-party talks, which became the basis for dialogue between these nations. Meanwhile, though, there were grave developments, including North Korea’s two nuclear experiments and a pronouncement that it now possessed nuclear weapons.

Last November, Morton Halperin, a former senior U.S. official, proposed a “comprehensive peace security agreement” to provide a breakthrough for the stalled six-party talks.

The proposal is a significant step in that it seeks to craft a treaty that will resolve the relevant issues in a comprehensive manner, rather than dealing with such issues separately, such as bringing the Korean War to an official end or making a mutual declaration of “no hostile intent.”

This is a good opportunity. With fresh momentum, we can strengthen the interest in a nuclear weapon-free zone for Northeast Asia by discussing Mr. Halperin’s proposal and taking a comprehensive approach to the region’s problems. It is a promising time.

Presentation

Keisaburo Toyonaga

Providing Support to A-bomb Survivors Overseas

I have been engaged in providing support to A-bomb survivors residing outside Japan, particularly in South Korea, for about 40 years. My first opportunity to visit South Korea was back in 1971, and I learned that the A-bomb survivors there were being neglected by the Japanese and South Korean governments.

“The Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims” was formed at the end of 1971. In 1978, a branch of the organization was established in Hiroshima. Since 1989, I have visited South Korea every year to interact with A-bomb survivors and record their experiences. We also began receiving such requests as helping them find people who witnessed their experience of the bombing, because witnesses are needed to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, and arranging accommodations for them when they visited Hiroshima. I believe that efforts like this can lead to building trust between people.

It’s true that some people in Asia feel that “the atomic bombings hastened their liberation.” But in order to realize a nuclear-free world, it’s important to convey to them the reality of the bombings through A-bomb exhibitions. At the same time, such exhibitions should show remorse over the fact that Hiroshima was a military city.

Profiles

Sergio Duarte

Born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1934. Concluded his study at the Brazilian Diplomatic Academy of Ministry of External Relations. From 1985, served as Ambassador of Brazil in a number of nations, including Nicaragua, Canada, China, and Croatia. Served as president of the 2005 NPT Review Conference Review Conference. Served as United Nations High Representative for Disarmament Affairs from 2007 to February 2012. Specializes in international law, public law, and disarmament diplomacy.

Hiromichi Umebayashi

Born in Hyogo Prefecture in 1937. Earned a Ph.D. in applied physics from the University of Tokyo Graduate School. Served in various posts, including as a university lecturer, before founding Peace Depot, a citizens’ think tank on nuclear and peace issues, in 1998. Became the first director of the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) at Nagasaki University, a body established in April 2012. Serves as the East Asia Coordinator of Parliamentarians for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (PNND).

Cheon Seongwhun

Born in Suwon City, South Korea in 1962. Graduated from the University of Waterloo in Canada with a Ph.D. in Management Science. Specializes in National Security and issues involving the Korean Peninsula. Has served as a policy advisor for the Ministry of National Defense, the Ministry of Unification, and the Crisis Management Office for the Presidential Office.

Hisako Iizuka

Born in Tokyo in 1964. Graduated from the Graduate School of Law, Keio University. Taught at International Christian University from 2008 to 2010, and at Tokiwa University from 2010 to 2011. Specializes in Contemporary Chinese Political Issues.

Yumi Kanazaki

Born in Noshiro, Akita Prefecture in 1970. Joined The Chugoku Shimbun in 1995. Mainly covers the atomic bombing and peace issues. Covered the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference in 2010, and has written feature series on nuclear issues, the realignment of U.S. forces, and other subjects.

Kazumi Mizumoto

Born in Hiroshima in 1957. Graduated from the University of Tokyo with a degree in law in 1981. Graduated from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University in the United States with a Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy in 1989. Specializes in international law, international relations, and nuclear arms reduction.

Keisaburo Toyonaga

Born in Yokohama in 1936. Moved to Hiroshima, his parents’ hometown, in 1939. Exposed to radiation when he entered the hypocenter area in August 1945, searching for his mother and brother. Graduated from Hiroshima University in 1961, then became a Japanese language teacher. Continues to be engaged in supporting A-bomb survivors residing outside Japan, mainly in South Korea.

This feature article was written by Rie Nii, Masaki Kadowaki, Kei Kinugawa, and Sakiko Masuda.

(Originally published on July 31, 2012)

Panelists

Sergio Duarte, Former High Representative, United Nations for Disarmament Affairs

Hiromichi Umebayashi, Director, Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University

Cheon Seongwhun, Senior Research Fellow, Korea Institute for National Unification (South Korea)

Hisako Iizuka, Researcher on Contemporary Chinese Political Issues

Yumi Kanazaki, Editorial Writer, The Chugoku Shimbun

Presenter

Keisaburo Toyonaga, Director of Hiroshima Branch, Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims

Moderator

Kazumi Mizumoto, Vice-President, Hiroshima Peace Institute, Hiroshima City University

The Challenges of Denuclearization

Ms. Iizuka: A stable region benefits China as well.

Mr. Duarte: In Central and South America, nations have changed their policies to emphasize dialogue.

Mizumoto: Separately from Mr. Umebayashi, Mr. Cheon has also proposed the denuclearization of Northeast Asia.

Cheon: In 2000, together with a Japanese researcher, I issued a proposal called the Trilateral Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (TNWFZ) in Northeast Asia with Japan, South Korea, and North Korea as the participating countries. The rationale behind this vision includes stemming North Korea’s atempts to go nuclear and ridding international suspicions over South Korea’s and Japan’s nuclear intentions, among other objectives.

However, the vision is hindered by North Korea’s nuclear development program. For instance, although North Korea had continued to deny it was pursuing such a program, contending that it had no nuclear capability or intention, the existence of its uranium enrichment facility surfaced in 2010.

Iizuka: China has strengthened its standing in the world since it first began building a nuclear arsenal in 1964. For China, its nuclear weapons are a symbol of “patriotism,” and serve as an anchor for uniting the nation.

Stability in Northeast Asia is absolutely crucial for China. In this sense it benefits China, too, if the international community presses North Korea to renounce nuclear weapons in order to promote the denuclearization of the region.

Duarte: A global model for a nuclear weapon-free zone treaty exists in Central and South America. But it faced challenges in the past. Brazil and Argentina, major regional powers, did not join the treaty until the 1990s. Both nations had been maintaining their nuclear development programs under military regimes, making them rivals. But when there was a change of administration in the two nations, their policies shifted to an emphasis on dialogue. The two nations built a relationship of mutual trust by undertaking such measures as establishing an organization to mutually inspect their civilian use of nuclear power, leading both countries to join the treaty in 1995.

Mizumoto: Countries in Central and South America succeeded in building a relationship of trust. Is it possible to achieve this in Northeast Asia?

Cheon: As the issue of North Korea’s nuclear development program clearly shows, they have shaken hands and worn smiles, while doing exactly the opposite behind the scenes. North Korea has deceived the international community. We must not forget its two faces.

Iizuka: It’s important to consider the denuclearization of the Northeast Asian region as one component of the total elimination of nuclear weapons from the earth. It’s essential to build trust as denuclearization is pursued.

Umebayashi: I see normalizing relations between Japan and North Korea as an important element in a comprehensive approach toward denuclearization. There is concern that the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and other security arrangements might stand in the way, yet the role played by military alliances will grow smaller as the region rids itself of nuclear arms.

Kanazaki: We must be more aware of multilayered approaches, such as increasing the number of nuclear weapon-free zones and seeking the early start of negotiations on a Nuclear Weapons Convention for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference to be held in 2015, which remains the most important framework for multinational nuclear disarmament.

Consequences of Fukushima

Mr. Cheon: It has led to an erosion of trust in nuclear power.

Ms. Kanazaki: Media coverage on the nuclear accident must have a multifaceted perspective.

Mizumoto: What changes have occurred since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant?

Duarte: The United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) have conferred over the response of the international community to the question of nuclear energy. They have concluded that each nation must decide its own policy. Despite the disaster in Fukushima, almost every nation that uses nuclear energy has continued to operate their nuclear power stations.

Iizuka: Campaigns against the construction of nuclear power plants have emerged in the inland areas of China, but they have not spread into a larger movement. The Chinese government is continuing to promote the construction of these plants. As for nuclear weapons, the government holds the view that possessing nuclear weapons gives China a greater voice in international affairs. Unless the United States abandons its own nuclear arsenal, China will continue to possess them.

Cheon: Even for South Korea, the accident at Fukushima was a great shock. An opinion poll conducted after the disaster showed that support for the use of nuclear energy fell to less than half of what it was prior to the accident. The peoples’ trust in nuclear power has deteriorated significantly.

Kanazaki: Atomic bombs aren’t the only things that produce radiation damage. We were aware of this, yet we weren’t sufficiently conscious of the danger. Among the non-nuclear weapon states, Japan is the only nation which extracts plutonium through the reprocessing of its spent nuclear fuel. It has amassed 45 tons of plutonium, equivalent to over 5,000 Nagasaki-type atomic bombs. As a journalist of a newspaper located in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, I would like to focus on the issue of nuclear power plants from a multifaceted perspective, while holding to the position of seeking the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Umebayashi: The biggest problem involving the use of nuclear power plants is the fact that we don’t have a way of disposing of the radioactive waste. Under these conditions, it’s only natural that we would choose not to build new plants, or at least hold off on building new plants until a method has been found to deal with the waste. If we’re unable to find a solution, we have to stop building nuclear plants.

The Role of the A-bombed Nation of Japan

Mr. Umebayashi: Japan must speak out in the international arena.

Mizumoto: What do you see as the role of the A-bombed nation of Japan?

Cheon: In June, Japan revised its Atomic Energy Basic Act, adding one phrase which indicates that nuclear energy should also have the objective of contributing to “national security.” Because of this move, I can’t help feeling some concern that this might open up a path toward Japan arming itself with nuclear weapons. Don’t these words contradict Japan’s three nonnuclear principles?

This revision to the law was not made with the consensus of the Japanese people. From this point forward, it will be important to watch the discourse in Japan carefully. The world has suspicions as to whether Japan’s three nonnuclear principles may be reversed.

Iizuka: There is a mutual sense of distrust between China and Japan. In China, people believe that Japan is equipped with the technology to make nuclear weapons and missiles if it chooses to do so. As for the revision of the Atomic Energy Basic Act, China has not criticized Japan for this move, but Chinese media has published articles in which South Korea is sharply critical. People in China may feel that their suspicions have been borne out. In this way the revision has widened the breach between the two nations.

Kanazaki: The activities pursued by Mr. Toyonaga and others can build trust. It’s important that all of us in Hiroshima consider what we can do, as individuals, for the denuclearization of Northeast Asia. The governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can hold humane discussions only if they listen with empathy to the accounts shared by A-bomb survivors.

Umebayashi: In April of this year, Katsuya Okada, the deputy prime minister of Japan, said in a statement at the Diet: “A nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia would be an effective means of getting North Korea to abandon its nuclear ambitions.” It’s a significant remark that has pushed the position of the Japanese government in this direction. Gaining some momentum from Mr. Okada’s comment, we must begin discussions on this issue. To put discussions of a nuclear weapon-free zone on the international agenda, the nations involved must initiate the process. The A-bombed nation of Japan must speak out proactively in the international arena.

Duarte: Hiroshima and Nagasaki hold memories of the horror of nuclear weapons. The same horror must not be repeated. To realize the abolition of nuclear weapons, Hiroshima and Nagasaki have an important role to play. My hope is that, with your unyielding spirit, you will make significant contributions toward creating a nuclear-free world.

Mizumoto: With tensions continuing in Northeast Asia, making repeated calls for denuclearization can help build trust among the people of this region.

Keynote Speeches

Sergio Duarte

Lessons of Latin American countries

In 1958, Costa Rica presented a draft resolution to the Council of the Organization of American States proposing the establishment of a nuclear weapon free zone in Latin America. Just weeks before the Cuban missile crisis, in 1962, Brazil introduced a resolution in the United Nations General Assembly with a similar goal. Although the Cuban missile crisis did not trigger action, it did serve to heighten the focus of public attention on the desirability of pursuing this project in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 1963, the Presidents of Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Mexico signed a Declaration setting forth the process that led to the negotiation and signature of the Tlatelolco Treaty only four years later.

I would like to point out in this context that Latin American States share a common Iberian heritage which is also an important part of the Caribbean history and experience. That element was obviously instrumental in garnering support for the Treaty. Moreover, our region can easily be described as the most peaceful in the world and our tradition of mutual respect and cooperation for economic and social development is certainly another factor that made the Tlatelolco Treaty possible in the uncertain times of the 1960’s.

The Treaty of Tlatelolco pioneered a model that would later inspire the creation of four other zones and the proposals for the Middle East and for Northeast Asia. When these two are realized, almost all inhabited areas of the Southern Hemisphere and a significant part of the Northern Hemisphere will be free of nuclear armaments. Maybe then the existing nuclear armed States and some of their allies will at long last take a hard look on their own policies and beliefs and join the rest of the world in doing away with nuclear arms forever.

Several States today continue to rely on nuclear weapons for their security. They still claim that the use of such weapons is legal and that they must be kept because they are supposed to be militarily effective in deterring aggression. Some claim that they provide an “insurance policy” and others pay lip service to nuclear disarmament, insisting that their weapons will be kept “as long as nuclear weapons exist”, which seems to be a convenient recipe for never relinquishing them.

I must emphasize here that security is not an exclusive requirement for powerful States. All States are entitled to it and nuclear weapon free zones should enhance everyone’s security.

We all recognize the distinctive features of the political and security realities in Northeast Asia and the obstacles that stand in the way. The experience of Tlatelolco, or for that matter that of the other regions which successfully established nuclear weapon free zones, cannot be transplanted elsewhere. Nuclear weapon free zones are indeed a very effective measure of non-proliferation. To truly make a difference in today’s world, however, they must be more than that: they must represent a concrete and meaningful step towards nuclear disarmament. I sincerely wish that with patience, realism and constructive spirit, the countries in this region will achieve that objective in a not too distant future.

The whole text of the keynote speech is here.

Hiromichi Umebayashi

A Good Opportunity for Discussing Denuclearization

Efforts aimed at creating a nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia have evolved from merely discussing its feasibility or its framework to the actual means of achieving this goal.

In 1996, I proposed the “three-plus-three vision.” This proposal envisions creating a nuclear weapon-free zone comprised of Japan, South Korea, and North Korea. At the same time, the nuclear weapon states in the region, namely the United States, China, and Russia, would pledge not to attack or threaten these nations with nuclear weapons. The objectives of this idea included discouraging a nuclear arms race, encouraging Japan and South Korea to leave the U.S. “nuclear umbrella,” and advancing the larger goal of eliminating nuclear weapons entirely.

Then came the framework known as the six-party talks, which became the basis for dialogue between these nations. Meanwhile, though, there were grave developments, including North Korea’s two nuclear experiments and a pronouncement that it now possessed nuclear weapons.

Last November, Morton Halperin, a former senior U.S. official, proposed a “comprehensive peace security agreement” to provide a breakthrough for the stalled six-party talks.

The proposal is a significant step in that it seeks to craft a treaty that will resolve the relevant issues in a comprehensive manner, rather than dealing with such issues separately, such as bringing the Korean War to an official end or making a mutual declaration of “no hostile intent.”

This is a good opportunity. With fresh momentum, we can strengthen the interest in a nuclear weapon-free zone for Northeast Asia by discussing Mr. Halperin’s proposal and taking a comprehensive approach to the region’s problems. It is a promising time.

Presentation

Keisaburo Toyonaga

Providing Support to A-bomb Survivors Overseas

I have been engaged in providing support to A-bomb survivors residing outside Japan, particularly in South Korea, for about 40 years. My first opportunity to visit South Korea was back in 1971, and I learned that the A-bomb survivors there were being neglected by the Japanese and South Korean governments.

“The Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims” was formed at the end of 1971. In 1978, a branch of the organization was established in Hiroshima. Since 1989, I have visited South Korea every year to interact with A-bomb survivors and record their experiences. We also began receiving such requests as helping them find people who witnessed their experience of the bombing, because witnesses are needed to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, and arranging accommodations for them when they visited Hiroshima. I believe that efforts like this can lead to building trust between people.

It’s true that some people in Asia feel that “the atomic bombings hastened their liberation.” But in order to realize a nuclear-free world, it’s important to convey to them the reality of the bombings through A-bomb exhibitions. At the same time, such exhibitions should show remorse over the fact that Hiroshima was a military city.

Profiles

Sergio Duarte

Born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1934. Concluded his study at the Brazilian Diplomatic Academy of Ministry of External Relations. From 1985, served as Ambassador of Brazil in a number of nations, including Nicaragua, Canada, China, and Croatia. Served as president of the 2005 NPT Review Conference Review Conference. Served as United Nations High Representative for Disarmament Affairs from 2007 to February 2012. Specializes in international law, public law, and disarmament diplomacy.

Hiromichi Umebayashi

Born in Hyogo Prefecture in 1937. Earned a Ph.D. in applied physics from the University of Tokyo Graduate School. Served in various posts, including as a university lecturer, before founding Peace Depot, a citizens’ think tank on nuclear and peace issues, in 1998. Became the first director of the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) at Nagasaki University, a body established in April 2012. Serves as the East Asia Coordinator of Parliamentarians for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (PNND).

Cheon Seongwhun

Born in Suwon City, South Korea in 1962. Graduated from the University of Waterloo in Canada with a Ph.D. in Management Science. Specializes in National Security and issues involving the Korean Peninsula. Has served as a policy advisor for the Ministry of National Defense, the Ministry of Unification, and the Crisis Management Office for the Presidential Office.

Hisako Iizuka

Born in Tokyo in 1964. Graduated from the Graduate School of Law, Keio University. Taught at International Christian University from 2008 to 2010, and at Tokiwa University from 2010 to 2011. Specializes in Contemporary Chinese Political Issues.

Yumi Kanazaki

Born in Noshiro, Akita Prefecture in 1970. Joined The Chugoku Shimbun in 1995. Mainly covers the atomic bombing and peace issues. Covered the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference in 2010, and has written feature series on nuclear issues, the realignment of U.S. forces, and other subjects.

Kazumi Mizumoto

Born in Hiroshima in 1957. Graduated from the University of Tokyo with a degree in law in 1981. Graduated from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University in the United States with a Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy in 1989. Specializes in international law, international relations, and nuclear arms reduction.

Keisaburo Toyonaga

Born in Yokohama in 1936. Moved to Hiroshima, his parents’ hometown, in 1939. Exposed to radiation when he entered the hypocenter area in August 1945, searching for his mother and brother. Graduated from Hiroshima University in 1961, then became a Japanese language teacher. Continues to be engaged in supporting A-bomb survivors residing outside Japan, mainly in South Korea.

This feature article was written by Rie Nii, Masaki Kadowaki, Kei Kinugawa, and Sakiko Masuda.

(Originally published on July 31, 2012)