My Life: Interview with Makoto Kitanishi, political scientist, Part 2

Jul. 4, 2013

Growing up in Hakata

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Rebellion against militaristic education

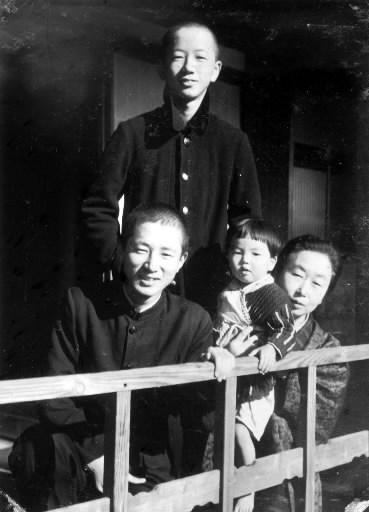

Mr. Kitanishi’s father, Tsurutaro, and his mother, Toyoko, were from Wakayama Prefecture. He was the youngest of three children, with an older sister and brother.

My father was teaching elementary school in Wakayama when he took a licensing examination and became a teacher at Kyoto No. 2 Junior High School. Then he taught at Osaka School of Foreign Languages (now the School of Foreign Studies at Osaka University). I was born in Kyoto, but we moved to Osaka before I turned 2, and I went to Takaishi Elementary School on the Nankai Line. But when I was in the third grade we moved to Fukuoka.

After my father supported a student strike in opposition to the education at the School of Foreign Languages, he didn’t get along with the principal, so he took a job at Fukuoka Prefectural College for Women (now Fukuoka Women’s University). He specialized in Japanese literature and did research on the “Okagami” tale of the Middle Ages and Edo period literature.

According to a publication issued by Osaka University’s School of Foreign Studies to mark its 70th anniversary, at the time of the Manchurian Incident in 1931, the school’s students staged a strike to oust the principal, and the first principal voluntarily retired in 1933. The times took on more of a wartime tenor.

Our house in Fukuoka was in what is now Hakata Ward, near Sumiyoshi Shrine. My mother was an “education mama,” and I attended Haruyoshi Elementary School, which was outside my school zone, because a lot of kids from that school went on to junior high school. Unlike in Osaka, for our morning assembly we had to face east and worship the emperor. I would fart on purpose and make my friends laugh. I gradually started being rebellious like that.

When I entered Fukuoka Junior High School (now Fukuoka High School), I was beaten by the teachers all the time, no matter whether my behavior was good or bad. It was drummed into us that “good Japanese die for the emperor.” The teachers stopped wearing suits and began wearing military-style national uniforms. I suppose it was the trend of the times, but when we got a principal who had graduated from Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now Hiroshima University), the education became even more militaristic.

My father talked pacifism at home, but he was an authoritarian. He never made my brother, who was three years older, split firewood or start the fire for the bath. I had to do all that. I felt like I was not the younger brother but the “lower brother,” and I resented it.

Those sorts of things built up, and I started to think about avoiding authority and the military. I spent one week drilling with the 24th Fukuoka Regiment. It was, as Hiroshi Noma wrote, truly a “zone of emptiness.” If someone didn’t fold his blanket properly, everyone was beaten. And a private first class would have them put their faces up to him as he lay on his bed, and then he’d hit them with a leather slipper.

When I went to see my brother, who had been drafted, his face was swollen. He said to me, “Rebellious guys like you will get killed before they’re sent to the front.” I thought seriously about how to stay out of the army.

(Originally published on April 10, 2013)

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Rebellion against militaristic education

Mr. Kitanishi’s father, Tsurutaro, and his mother, Toyoko, were from Wakayama Prefecture. He was the youngest of three children, with an older sister and brother.

My father was teaching elementary school in Wakayama when he took a licensing examination and became a teacher at Kyoto No. 2 Junior High School. Then he taught at Osaka School of Foreign Languages (now the School of Foreign Studies at Osaka University). I was born in Kyoto, but we moved to Osaka before I turned 2, and I went to Takaishi Elementary School on the Nankai Line. But when I was in the third grade we moved to Fukuoka.

After my father supported a student strike in opposition to the education at the School of Foreign Languages, he didn’t get along with the principal, so he took a job at Fukuoka Prefectural College for Women (now Fukuoka Women’s University). He specialized in Japanese literature and did research on the “Okagami” tale of the Middle Ages and Edo period literature.

According to a publication issued by Osaka University’s School of Foreign Studies to mark its 70th anniversary, at the time of the Manchurian Incident in 1931, the school’s students staged a strike to oust the principal, and the first principal voluntarily retired in 1933. The times took on more of a wartime tenor.

Our house in Fukuoka was in what is now Hakata Ward, near Sumiyoshi Shrine. My mother was an “education mama,” and I attended Haruyoshi Elementary School, which was outside my school zone, because a lot of kids from that school went on to junior high school. Unlike in Osaka, for our morning assembly we had to face east and worship the emperor. I would fart on purpose and make my friends laugh. I gradually started being rebellious like that.

When I entered Fukuoka Junior High School (now Fukuoka High School), I was beaten by the teachers all the time, no matter whether my behavior was good or bad. It was drummed into us that “good Japanese die for the emperor.” The teachers stopped wearing suits and began wearing military-style national uniforms. I suppose it was the trend of the times, but when we got a principal who had graduated from Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now Hiroshima University), the education became even more militaristic.

My father talked pacifism at home, but he was an authoritarian. He never made my brother, who was three years older, split firewood or start the fire for the bath. I had to do all that. I felt like I was not the younger brother but the “lower brother,” and I resented it.

Those sorts of things built up, and I started to think about avoiding authority and the military. I spent one week drilling with the 24th Fukuoka Regiment. It was, as Hiroshi Noma wrote, truly a “zone of emptiness.” If someone didn’t fold his blanket properly, everyone was beaten. And a private first class would have them put their faces up to him as he lay on his bed, and then he’d hit them with a leather slipper.

When I went to see my brother, who had been drafted, his face was swollen. He said to me, “Rebellious guys like you will get killed before they’re sent to the front.” I thought seriously about how to stay out of the army.

(Originally published on April 10, 2013)