My Life: Interview with Makoto Kitanishi, political scientist, Part 10

Jul. 4, 2013

Schism

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Guilt-ridden over factional conflict

In 1963 the ban-the-bomb movement split as the result of the conflict between the Socialist and Communist parties. On August 5 of that year the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union signed a treaty banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere, in outer space and underwater.

China fiercely opposed the move to establish a test ban treaty. I also wavered, but I felt that China’s assertion that the treaty gave the three countries a monopoly on nuclear weapons made sense. On the other hand, Ichiro Moritaki, who was a member of the representative committee of the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Hiroshima Gensuikyo), praised the treaty because it got the U.S. and the Soviet Union to sit down at the same table. He felt it was the first step toward a total ban. The committee members from the General Council of Trade Unions even called for praising the treaty to be made a principle of the movement.

But the Hiroshima Gensuikyo wanted to preserve unity and not bring the conflict between the leaders of the Socialist and Communist parties into it. Mr. Moritaki and Mr. Sakuma collaborated on the draft of the keynote report for the 9th World Conference against Atomic & Hydrogen Bombs, which was held in 1963.

The biggest issue was “opposition to nuclear tests by any nation.” This was changed to the rather labored expression “any kind of nuclear test of any nation,” but language praising the partial test ban treaty was included. I wasn’t happy about it, but the start of the opening session was approaching and it was referred to as “a proposal by the Hiroshima Gensuikyo,” so I agreed to it.

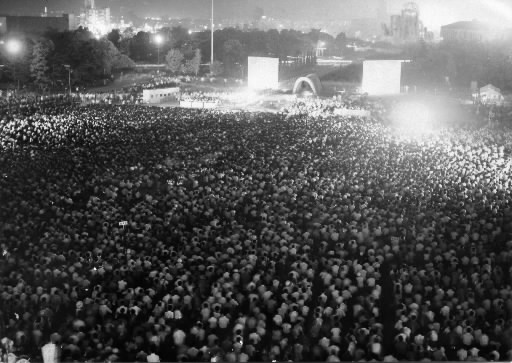

(Just after 8 p.m. on August 5) Mr. Moritaki began to present the keynote report in front of the memorial cenotaph. People started leaving in droves. The leadership of the General Council of Trade Unions had decided to boycott the conference without notifying the Hiroshima Gensuikyo. They couldn’t match the Communist Party in terms of their ability to mobilize the participants. They must have been afraid their assertions would be reversed at the conference.

The Hiroshima Gensuikyo had agreed to put on the 9th World Conference in hopes of maintaining unity, but after that they had to turn it back over to the Japan Gensuikyo. A decision was made in the wee hours of August 6, and at that point the conference essentially became a Communist Party faction event. The party leaders were triumphant, but I had tried to stay out of it and felt we should avoid a schism, so I drafted a resolution for the conference.

According to “The Ban-the-Bomb Movement” published in 1974 and written by Seiji Imabori, a professor at Hiroshima University, Mr. Kitanishi’s draft was substantially revised, and the resolution by the 9th World Conference was “dominated by anti-imperial and anti-U.S. sentiment.”

I concluded my resolution by saying, “We must not put unresolved issues on the back burner and discuss them patiently.” When I got home I had a high fever. My wife called a doctor, and I couldn’t attend the closing session. So my resolution was rewritten. I regretted that ordinary citizens were no longer involved in the movement, but I had also argued bitterly. I was a party to the schism, and I’m still ashamed and guilt-ridden about it.

(Originally published on April 20, 2013)

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Guilt-ridden over factional conflict

In 1963 the ban-the-bomb movement split as the result of the conflict between the Socialist and Communist parties. On August 5 of that year the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union signed a treaty banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere, in outer space and underwater.

China fiercely opposed the move to establish a test ban treaty. I also wavered, but I felt that China’s assertion that the treaty gave the three countries a monopoly on nuclear weapons made sense. On the other hand, Ichiro Moritaki, who was a member of the representative committee of the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Hiroshima Gensuikyo), praised the treaty because it got the U.S. and the Soviet Union to sit down at the same table. He felt it was the first step toward a total ban. The committee members from the General Council of Trade Unions even called for praising the treaty to be made a principle of the movement.

But the Hiroshima Gensuikyo wanted to preserve unity and not bring the conflict between the leaders of the Socialist and Communist parties into it. Mr. Moritaki and Mr. Sakuma collaborated on the draft of the keynote report for the 9th World Conference against Atomic & Hydrogen Bombs, which was held in 1963.

The biggest issue was “opposition to nuclear tests by any nation.” This was changed to the rather labored expression “any kind of nuclear test of any nation,” but language praising the partial test ban treaty was included. I wasn’t happy about it, but the start of the opening session was approaching and it was referred to as “a proposal by the Hiroshima Gensuikyo,” so I agreed to it.

(Just after 8 p.m. on August 5) Mr. Moritaki began to present the keynote report in front of the memorial cenotaph. People started leaving in droves. The leadership of the General Council of Trade Unions had decided to boycott the conference without notifying the Hiroshima Gensuikyo. They couldn’t match the Communist Party in terms of their ability to mobilize the participants. They must have been afraid their assertions would be reversed at the conference.

The Hiroshima Gensuikyo had agreed to put on the 9th World Conference in hopes of maintaining unity, but after that they had to turn it back over to the Japan Gensuikyo. A decision was made in the wee hours of August 6, and at that point the conference essentially became a Communist Party faction event. The party leaders were triumphant, but I had tried to stay out of it and felt we should avoid a schism, so I drafted a resolution for the conference.

According to “The Ban-the-Bomb Movement” published in 1974 and written by Seiji Imabori, a professor at Hiroshima University, Mr. Kitanishi’s draft was substantially revised, and the resolution by the 9th World Conference was “dominated by anti-imperial and anti-U.S. sentiment.”

I concluded my resolution by saying, “We must not put unresolved issues on the back burner and discuss them patiently.” When I got home I had a high fever. My wife called a doctor, and I couldn’t attend the closing session. So my resolution was rewritten. I regretted that ordinary citizens were no longer involved in the movement, but I had also argued bitterly. I was a party to the schism, and I’m still ashamed and guilt-ridden about it.

(Originally published on April 20, 2013)