Sumiko Ogata, 80, Hatsukaichi City

Aug. 1, 2012

A body scarred, a life of pain and anxiety

Black rain brought on vomiting by the river

Bleeding gums, hair loss, purple spots spreading on the skin: these were the symptoms suffered by a 13-year-old girl, symptoms that chilled her with the horror of A-bomb death. Even today, when Sumiko Ogata (nee Miyoshi), 80, thinks back to that day, her eyes fill with tears and her voice trembles.

Back then, Ms. Ogata was in her second year at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School. As one of the many students mobilized for the war effort, she was spending her days helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the Zakoba district, part of present-day Naka Ward. But on August 6, the day of the atomic bombing, she was feeling poorly and so she stayed home in Nishishin-machi.

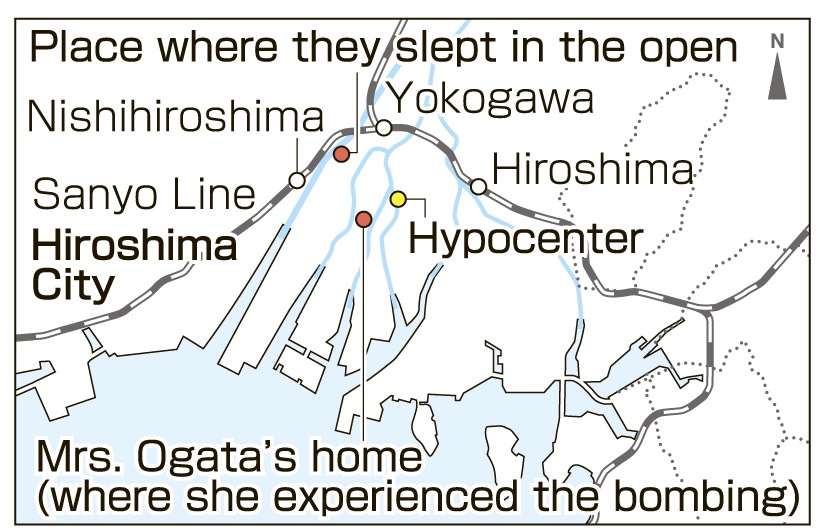

The area where her house sat was located just 700 meters from the hypocenter. When the bomb exploded with a roar, she was knocked unconscious. Coming to, she found herself beneath a chest of drawers. With all her might, she managed to crawl out. Then, along with her aunt, Akiko Sera, then 32, who had been living with her family, she helped her younger brothers Yoshiaki, 4, and Hiroaki, 3, who were pinned under the wreckage of their home. She and her aunt carried the boys on their backs, hiking to an evacuation site in the Yamate district, now part of Nishi Ward. Her father was not at home as he was off fighting on the front lines.

When they reached the Yamate River, at the entrance to the Yamate district, they didn’t have the strength to continue walking. So they sat down to rest and, after a while, the black rain began to fall like an evening shower. Ms. Ogata then suffered from vomiting and diarrhea and wasn’t able to leave the river bank. They stayed by the river until the next morning.

On August 7, they were reunited with Ms. Ogata’s mother, Masano, then 38, who had gone to the village of Sagotani, in present-day Saeki Ward, to see her son Kuniaki, 11. Kuniaki was evacuated there with other schoolchildren before the bombing took place. Masano went to Sagotani on August 5. The family slept outside by the river for about a week, and then traveled to the village of Gono (now, the town of Yoshida), located north of Hiroshima Prefecture, to seek medical treatment and the chance to regain their strength. This was the evacuation site of Masano’s aunt and uncle.

Ms. Ogata and Akiko both came down with purplish spots on their skin, their hair fell out in handfuls, and their gums bled. Ms. Ogata, suffering a persistently high fever, finally fell unconscious. When she awoke, in early September, she learned that Akiko was dead.

Ms. Ogata then experienced terrible pain, with pus oozing from wounds to her back and her right arm. “It was frightening because I wasn’t sure where all that pus was coming from,” she said, recalling that time. At the hospital, a large amount of pus was removed from her left buttocks to her groin, but afterward, that part of her body became hollowed out. Even today, pain prevents her from sitting with her legs out to one side. She bears a scar on her arm as well.

Ms. Ogata got married at the age of 22. Her constitution is weak, though, and she has been hospitalized many times. Although A-bomb survivors often suffered from discrimination when it came time to seek a marriage partner, her father-in-law, an A-bomb survivor himself, dismissed such fears and the marriage was arranged. She feels happy to have borne a son and a daughter, but, at the same time, has always been anxious about her exposure to the atomic bombing possibly affecting her children in some way.

More than 300 of her schoolmates who were laboring in the Zakoba district and at other sites on August 6 lost their lives in the atomic blast. Starting five years ago, she has been visiting her alma mater to relate her account of the atomic bombing to today’s students. “I have to speak out, for my friends,” she said.(Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight: Evacuation of children from the city

Sheltered in the countryside to escape air raids

With the war intensifying, and air raids feared, elementary school children from the third to the sixth grades were evacuated from urban areas in Japan and taken in their school groups to temples and community centers in the countryside.

The guidelines for these evacuations were issued by the Japanese government in June 1944 and schools in the city of Hiroshima began evacuating children in April 1945.

According to a report citing evacuations from Hiroshima, roughly 9,000 children from 36 of the 41 elementary schools in the city were evacuated to outlying areas, including Saeki Ward and the city of Miyoshi.

Removed from their families, the children felt homesick. When one child began crying at bedtime, the tears of other children, held back for a time, began to flow, too. The result was a chorus of sobbing. Some children even tried to flee and return home. The situation was compounded by the hunger the children suffered due to a lack of food.

Some of the children who survived ended up losing their entire family to the atomic bomb.

Teenagers' Impressions

Having appreciation for our abundance

Ms. Ogata told us that if the war had ended a month later, they all would have died of hunger. Because of the shortage of food at that time, their meals consisted of only about 5 or 10 soy beans. I thought about how much abundance we have now, being able to eat three good meals a day as well as having snacks between meals. We shouldn’t take all this for granted and I want to keep this sense of appreciation in mind. (Saya Teranishi, 15)

Desire for nuclear abolition has been strengthened

It was nice to hear that she feels happy now with her family. At the same time, I felt sorry about her undergoing an operation for thyroid cancer five years ago. The war came to an end 66 years ago, but she still continues to suffer from the damage caused by the bomb’s radiation. When she said, “Abolishing nuclear weapons is the most important thing for making the world a peaceful place,” it strengthened my own wish for nuclear abolition. (Mizuki Yada, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Looking back at the days of war, Ms. Ogata said, “It was a tense time.” If people expressed any sort of opposition to the war, such as “I hate war” or “I hope the war ends soon,” they could face arrest by the military police. Ms. Ogata still recalls an incident that occurred at the beginning of 1945. After two Americans, who had been working as English teachers at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School, returned to their homeland, their desks and books were burned in the middle of the school ground. “I didn’t understand everything, but I enjoyed the English lessons,” she said. “I appreciated their teaching, but then all their things were burned, so I didn’t know what to think.”

The Great East Japan Earthquake struck the nation on March 11, 2011. As she followed news reports on the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, she grew concerned about the potential harm to the children of Fukushima from radiation. Recalling her own operation for thyroid cancer five years ago, she said, “It’s frightening not knowing how and when radiation might cause harm to the body.” She now believes that both nuclear weapons and nuclear energy must be abolished. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on March 12, 2012)