Kunihiko Hashimoto, 80, Minami Ward, Hiroshima

Aug. 1, 2012

Delving into the fates of A-bombed schoolmates

Shock dulls pain of glass fragments in head and cheek

“I want to devote myself to working for peace so my friends won’t have died in vain.” Every August, Kunihiko Hashimoto, 80, attends the memorial service for the atomic bombing held at Midorimachi Junior High School (formerly, Hiroshima Municipal Third National School) and reaffirms his resolve. At the time of the bombing, Mr. Hashimoto was 13 years old and in his second year at this school. Many of his schoolmates perished in the blast that day.

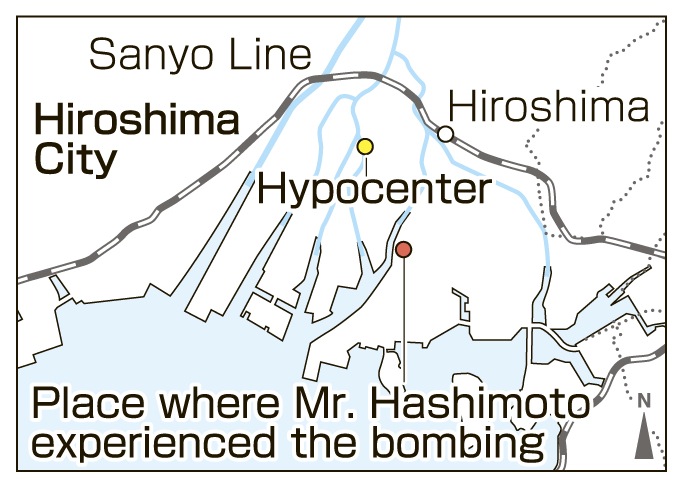

On August 6, 1945, 209 students from the school, both first- and second-year students were mobilized to help dismantle buildings in the Zakoba part of town, in present-day Naka Ward, to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. When the bomb exploded, they were just one kilometer from the hypocenter, and 143 students died.

Only the day before, on August 5, Mr. Hashimoto happened to be working at the same location. But his teacher told them, “Tomorrow, another class will take over the work here.” As a result, he managed to survive.

On August 6, the factory where he was normally mobilized to work was closed. And so Mr. Hashimoto was at home in Minamimachi, about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. When a whitish-blue flash of light poured through the windows, he instantly hit the floor.

When he opened his eyes, he saw that the roof of the house had been blown off and the windows were shattered. He left the house, calling for his mother Ko, then 36, and found her nearby.

His mother’s head was bleeding, but she focused on her son, removing bits of broken glass from Mr. Hashimoto’s head, right cheek, and right leg. He doesn’t recall feeling much pain, though, probably because he was in shock.

At the time of the bombing, his father Fumiichi, 38, was a streetcar operator and he experienced the blast near the terminal of the Eba line, in present-day Funairikawaguchi-cho. He suffered burns to his chest and both arms, and arrived home that evening. Although his burns eventually healed, his health was never the same and he became too weak to work a steady job.

As a result, Mr. Hashimoto and his sister Hatsune, two years older, were forced to work to help support the family. “But I didn’t want others to pass me by,” so he went to night school at the same time and was able to graduate from junior college at the age of 31.

In 1979, his mother developed leukemia and she passed away in 1985. She was 76.

All the while, Mr. Hashimoto felt indebted to his schoolmates for the fact that he survived. After his retirement in 1997, he began delving into the A-bomb fates of these students and relating his own A-bomb account at schools and community centers.

When he speaks to teenagers, he urges them to “Make the most of today. Set your own goals and work hard to move toward them.”

Mr. Hashimoto hopes that people who didn’t experience the atomic bombing directly will still speak out on the issue. “Be a messenger of peace,” he said, “and try to convey what happened to as many people as you can.”(Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight: Hiroshima Municipal Third National School

Student register prompts investigation

Midorimachi Junior High School adopted this name in 1949. The school was originally established in 1939 and known as the Hiroshima Municipal Third National School starting in 1941. The school offered a two-year course of studies for students who had completed six years of compulsory elementary-level education.

According to Midorimachi Junior High School, the school once had a large enrollment of 1,100 students, but after evacuations to the countryside took place during the war, the number declined to 310 students by 1945.

A record of the damage suffered by the school as a result of the atomic bombing indicates that the death toll included 143 students involved in dismantling buildings in the Zakoba area and nine students who were working at a power company in Tatemachi.

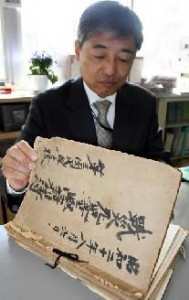

After a school register containing a list of victims was found in the school office, the school made an effort to learn what happened to the school community amid the atomic bombing. The student council took the lead in listening to the accounts of surviving students and teachers, and a booklet entitled “Blank School Register” was produced in 1980. The booklet is now used as a supplemental reader for peace education classes at the school.

Teenagers' Impressions

I want to listen to the A-bomb accounts of many survivors

He thanked us for listening to his story. But I felt that I’m the one who should be thanking him for telling us his account when there were so many things he didn’t really want to remember. We are the last generation with the chance to hear the experiences of the bombing directly from the survivors. I intend to listen to the A-bomb accounts of as many people as possible, and hand them down to the next generation. (Kanna Inoue, 16)

We have a responsibility to learn about and convey the bombing

I was most impressed by his words: “I may not want to do it, but I have a duty to convey my experience of the atomic bombing to other people.” And it’s our responsibility to do our best to take in these experiences, learn more about the bombing, and convey this information to others. I feel encouraged by the fact that Mr. Hashimoto has done his best despite his hardships, and I’m motivated to work hard toward my goals, too. (Kana Kumagai, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

We paid a visit to Midorimachi Junior High School with Mr. Hashimoto. On the grounds of the school, where the monument to the victims of the bombing now stands, we saw students of the tennis team cheerfully practicing after school.

The monument to the dead was erected by the families of the victims in 1946, the year after the bombing. Japan was under occupation by the Allied Forces during this time, which meant that voices speaking about the A-bomb damage were muffled. Some people visited the monument to offer flowers, but no ceremonies were held in front of the monument back then.

Eventually the monument became buried. The circumstances are not clear, but when a new gymnasium was constructed on the grounds, the monument, which should have been moved, was apparently left in place and covered over with earth. In 1971, teachers of the school dug it out.

Each summer, Midorimachi Junior High School holds a memorial service for the A-bomb victims. In 1980, the school produced a booklet entitled “Blank School Register” after researching the damage that had been suffered by the school community, known at the time as the Hiroshima Municipal Third National School. The school is now actively engaged in peace education.

Mr. Hashimoto has felt guilt over having survived. Watching the students on the school grounds, he said, “I feel comforted by the children’s lively voices.” He added that he deeply appreciates the fact that the memorial service is held every year and he entrusts these children, who will be the leaders of tomorrow, with peace in the future. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on March 26, 2012)