Hideo Kimura, 77, and Masae Kimura, 73, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Oct. 5, 2012

Handing down A-bomb sorrows to grandson in Fukushima

A-bomb accounts shared for first time after nuclear accident

Every August 6, Masae Kimura (nee Hiromoto), 73, and her husband, Hideo, 77, visit Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the heart of the city. It was at this location that both lost family members in the atomic bombing. When war is waged, they say, innocent children and civilians become victims. “We want a peaceful world,” the couple says.

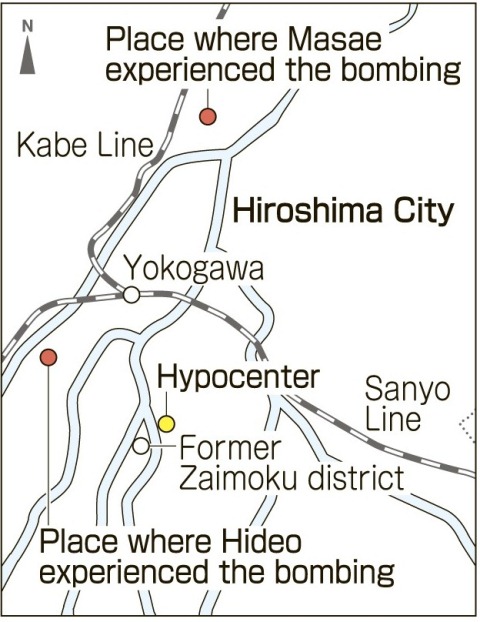

Masae was 6 years old on August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped. Her father died in battle in 1944, and her mother and paternal grandfather ran the family’s barber shop in the Zaimoku-cho district (now part of Nakajima-cho in Naka Ward), close to the hypocenter.

Two years earlier, at the age of 4, Masae was evacuated to her maternal grandparents’ home in Gion-cho (part of present-day Asaminami Ward). On the morning of the bombing, she was in the schoolyard of Nagatsuka National School (now Nagatsuka Elementary School), about 4.1 kilometers from the hypocenter. She recalls how the windows of the school building were shattered by the blast, scattering glass everywhere.

The day before the bombing, her mother, grandfather, and two-year-old sister visited the house in Gion-cho, and they had dinner together. But it would be the last time they were together as a family. Back in Zaimoku-cho the next morning, all three died in the blast.

Two days later, her maternal grandparents showed her boxes containing the bones of her mother, her sister, and her grandfather. She was told that her sister’s body hadn’t been completely burned, and that soldiers helped cremate her remains. “I think it was because my mother risked her own life trying to save my sister,” Masae said.

After the atomic bombing, Masae grew up with her maternal grandparents. When she reflects on her mother’s feelings, having to die while leaving her daughter behind, she can’t help shedding tears.

For his part, Hideo was 10 years old at the time, and he experienced the A-bombing alongside a temporary school building on the grounds of Misasa National School (present-day Misasa Elementary School). The school was located near his home in Nakahiro-cho (part of today’s Nishi Ward), about 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. While standing outside the school building, waiting for the school day to begin, he noticed an airplane overhead. Suddenly, there was a great flash, and he dashed into a ditch for cover. Then he heard a huge boom.

Because he was sheltered in the shadow of the wall, he wasn’t burned or injured. Returning to his home, now ablaze, he found his mother and two elder sisters nearby, and they fled toward a mountain together. Later, they sought refuge at Honkawa National School (now Honkawa Elementary School in Naka Ward). There, Hideo helped cremate the remains of A-bomb victims.

Another elder sister, however, was working at the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (today’s A-bomb Dome) when the atomic bomb exploded. Her body was never found. Instead, Hideo and his family carried home earth from beside the building and have preserved it in her memory.

Hideo and Masae met at the same workplace and married in 1962. One of their grandchildren is now studying at Fukushima University in the city of Fukushima. After the critical accident at the nuclear power plant in that area, they shared their experiences of the atomic bombing with their grandson for the first time.

“Nuclear power plants are horrible things,” Hideo said. “They can be used to produce nuclear weapons. We need alternatives to nuclear energy.” Expressing her hopes, Masae said, “I would like the younger generations to think carefully so the experience suffered by Hiroshima will never be repeated.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

The Zaimoku-cho district: Stone monument raised for the victims

The Zaimoku-cho district was once a part of today’s Nakajima area. Zaimoku-cho lay from the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims to Peace Memorial Museum and the southern side of Peace Fountain. The name Zaimoku-cho was used until 1965, when the city’s address system was revamped.

In English, “zaimoku” means “timber,” and this designation for the district is said to have originated from the fact that the area was home to many lumber dealers. According to Hiroshima City Hall, however, the number of lumber dealers declined around the beginning of the Showa period, which meant there were few lumber dealers left in the district at the time of the atomic bombing.

The Zaimoku-cho district was a lively area, featuring the Seigan Temple, known for its massive main gate, and shops selling rice, vegetables, meat, noodles, and sweets. The barber shop run by Masae Kimura’s mother and grandfather moved here from the neighboring Nakajima-shinmachi district, part of their evacuation effort prior to the bombing. However, the atomic bomb annihilated this area.

Some residents of the Zaimoku-cho district, who survived by being away from the area that day, were forced to move by the early 1950s when Peace Memorial Park was being constructed.

In 1957, former residents of the Zaimoku-cho district erected a stone monument to remember their old neighborhood and offer prayers for the A-bomb victims. The monument, inscribed with the words “Site of the Zaimoku-cho District,” continues to stand silently in Peace Memorial Park.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I won’t forget her tears When Mrs. Kimura was sharing her account of the atomic bombing, and thought about her mother, who died that day, she began to cry. That’s something I won’t forget. It must have been so sad to lose her family like that when she was little; I imagine she felt really lonely. I want to appreciate my everyday life, with my parents always by my side, and us enjoying our meals together. (Risa Murakoshi, 16)

I was shocked by what he experienced at the age of 10

When I first heard how Mr. Kimura, at the age of 10, was helping to cremate the bodies of the A-bomb victims, I was shocked to learn that young children had to do such things. Both Mr. Kimura and Mrs. Kimura told us their experiences because they hope we won’t “let the truth of the atomic bombing fade away.” I appreciate that and I feel it’s my mission to convey what they told me to my friends of the younger generation. (Junichi Akiyama, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

“It was as if they went home to die,” said Masae Kimura. Her mother and younger sister had returned from the place of Masae’s evacuation in Gion-cho (part of today’s Asaminami Ward) to their home early in the morning of August 6. As her mother was running a barber shop, she had to be there to do her work.

Then, at 8:15 that morning, the lives of her mother and sister were stolen away in an instant. At the site of the charred barber shop, an ashtray from the shop was found. For more than 67 years Masae has carefully preserved that ashtray as a memento of her family.

At the end of this past August, she tried retracing the path walked by her mother and sister from Gion-cho to Zaimoku-cho that day. “If they had returned home a bit later, they might have survived,” she said. Reflecting on the cruelty of fate, her eyes filled with tears. In today’s Peace Memorial Park, the place where her mother and sister died, she sprinkled water in their memory.

Along with former classmates, she has recorded her sorrows in writing: the loss of her family and her experience of the bombing. She plans to share this written account with her grandson studying at Fukushima University, asking that he share it with his friends at the university. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on September 24, 2012)

A-bomb accounts shared for first time after nuclear accident

Every August 6, Masae Kimura (nee Hiromoto), 73, and her husband, Hideo, 77, visit Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the heart of the city. It was at this location that both lost family members in the atomic bombing. When war is waged, they say, innocent children and civilians become victims. “We want a peaceful world,” the couple says.

Masae was 6 years old on August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped. Her father died in battle in 1944, and her mother and paternal grandfather ran the family’s barber shop in the Zaimoku-cho district (now part of Nakajima-cho in Naka Ward), close to the hypocenter.

Two years earlier, at the age of 4, Masae was evacuated to her maternal grandparents’ home in Gion-cho (part of present-day Asaminami Ward). On the morning of the bombing, she was in the schoolyard of Nagatsuka National School (now Nagatsuka Elementary School), about 4.1 kilometers from the hypocenter. She recalls how the windows of the school building were shattered by the blast, scattering glass everywhere.

The day before the bombing, her mother, grandfather, and two-year-old sister visited the house in Gion-cho, and they had dinner together. But it would be the last time they were together as a family. Back in Zaimoku-cho the next morning, all three died in the blast.

Two days later, her maternal grandparents showed her boxes containing the bones of her mother, her sister, and her grandfather. She was told that her sister’s body hadn’t been completely burned, and that soldiers helped cremate her remains. “I think it was because my mother risked her own life trying to save my sister,” Masae said.

After the atomic bombing, Masae grew up with her maternal grandparents. When she reflects on her mother’s feelings, having to die while leaving her daughter behind, she can’t help shedding tears.

For his part, Hideo was 10 years old at the time, and he experienced the A-bombing alongside a temporary school building on the grounds of Misasa National School (present-day Misasa Elementary School). The school was located near his home in Nakahiro-cho (part of today’s Nishi Ward), about 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. While standing outside the school building, waiting for the school day to begin, he noticed an airplane overhead. Suddenly, there was a great flash, and he dashed into a ditch for cover. Then he heard a huge boom.

Because he was sheltered in the shadow of the wall, he wasn’t burned or injured. Returning to his home, now ablaze, he found his mother and two elder sisters nearby, and they fled toward a mountain together. Later, they sought refuge at Honkawa National School (now Honkawa Elementary School in Naka Ward). There, Hideo helped cremate the remains of A-bomb victims.

Another elder sister, however, was working at the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (today’s A-bomb Dome) when the atomic bomb exploded. Her body was never found. Instead, Hideo and his family carried home earth from beside the building and have preserved it in her memory.

Hideo and Masae met at the same workplace and married in 1962. One of their grandchildren is now studying at Fukushima University in the city of Fukushima. After the critical accident at the nuclear power plant in that area, they shared their experiences of the atomic bombing with their grandson for the first time.

“Nuclear power plants are horrible things,” Hideo said. “They can be used to produce nuclear weapons. We need alternatives to nuclear energy.” Expressing her hopes, Masae said, “I would like the younger generations to think carefully so the experience suffered by Hiroshima will never be repeated.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

The Zaimoku-cho district: Stone monument raised for the victims

The Zaimoku-cho district was once a part of today’s Nakajima area. Zaimoku-cho lay from the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims to Peace Memorial Museum and the southern side of Peace Fountain. The name Zaimoku-cho was used until 1965, when the city’s address system was revamped.

In English, “zaimoku” means “timber,” and this designation for the district is said to have originated from the fact that the area was home to many lumber dealers. According to Hiroshima City Hall, however, the number of lumber dealers declined around the beginning of the Showa period, which meant there were few lumber dealers left in the district at the time of the atomic bombing.

The Zaimoku-cho district was a lively area, featuring the Seigan Temple, known for its massive main gate, and shops selling rice, vegetables, meat, noodles, and sweets. The barber shop run by Masae Kimura’s mother and grandfather moved here from the neighboring Nakajima-shinmachi district, part of their evacuation effort prior to the bombing. However, the atomic bomb annihilated this area.

Some residents of the Zaimoku-cho district, who survived by being away from the area that day, were forced to move by the early 1950s when Peace Memorial Park was being constructed.

In 1957, former residents of the Zaimoku-cho district erected a stone monument to remember their old neighborhood and offer prayers for the A-bomb victims. The monument, inscribed with the words “Site of the Zaimoku-cho District,” continues to stand silently in Peace Memorial Park.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I won’t forget her tears When Mrs. Kimura was sharing her account of the atomic bombing, and thought about her mother, who died that day, she began to cry. That’s something I won’t forget. It must have been so sad to lose her family like that when she was little; I imagine she felt really lonely. I want to appreciate my everyday life, with my parents always by my side, and us enjoying our meals together. (Risa Murakoshi, 16)

I was shocked by what he experienced at the age of 10

When I first heard how Mr. Kimura, at the age of 10, was helping to cremate the bodies of the A-bomb victims, I was shocked to learn that young children had to do such things. Both Mr. Kimura and Mrs. Kimura told us their experiences because they hope we won’t “let the truth of the atomic bombing fade away.” I appreciate that and I feel it’s my mission to convey what they told me to my friends of the younger generation. (Junichi Akiyama, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

“It was as if they went home to die,” said Masae Kimura. Her mother and younger sister had returned from the place of Masae’s evacuation in Gion-cho (part of today’s Asaminami Ward) to their home early in the morning of August 6. As her mother was running a barber shop, she had to be there to do her work.

Then, at 8:15 that morning, the lives of her mother and sister were stolen away in an instant. At the site of the charred barber shop, an ashtray from the shop was found. For more than 67 years Masae has carefully preserved that ashtray as a memento of her family.

At the end of this past August, she tried retracing the path walked by her mother and sister from Gion-cho to Zaimoku-cho that day. “If they had returned home a bit later, they might have survived,” she said. Reflecting on the cruelty of fate, her eyes filled with tears. In today’s Peace Memorial Park, the place where her mother and sister died, she sprinkled water in their memory.

Along with former classmates, she has recorded her sorrows in writing: the loss of her family and her experience of the bombing. She plans to share this written account with her grandson studying at Fukushima University, asking that he share it with his friends at the university. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on September 24, 2012)