Kayoko Yamashita, 77, Saka, Hiroshima Prefecture

Dec. 5, 2012

Sought shelter under a stove with younger sister

After the bombing, slept on the riverbank, saw bodies in the water

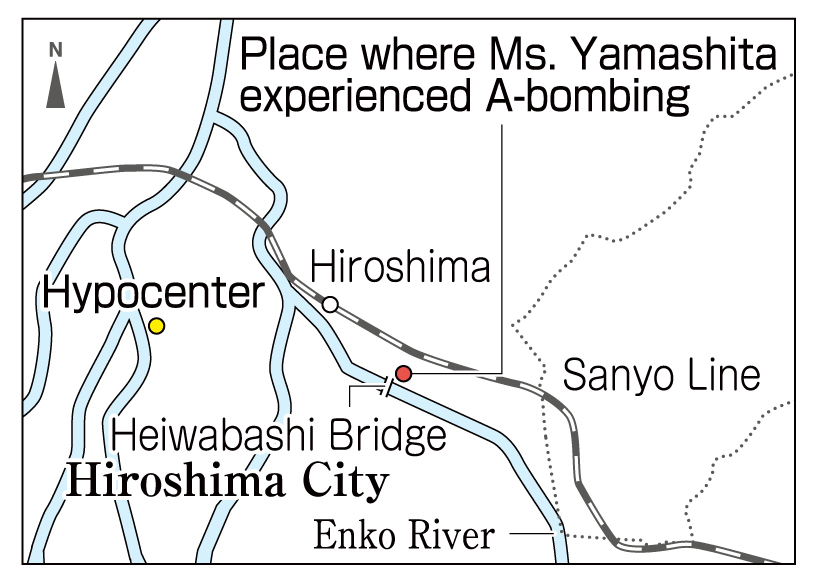

When the atomic bomb exploded, Kayoko Yamashita (nee Munemasa), who was nine years old at the time, held her three-year-old sister Mitsuko and hid under a cooking stove. They were roughly 3 kilometers from the hypocenter and managed to avoid serious injury.

Ms. Yamashita lived in Minamikaniyacho (part of present-day Minami Ward). She would cross the Enko River to attend Hijiyama National School (today’s Hijiyama Elementary School in Minami Ward), but near the end of the war, she went to a classroom at a temple near her home, instead of school. She wasn’t evacuated to the countryside, like many other children, because her family had decided: “If we die, we’ll die together as a family.”

The morning of August 6, 1945 began typically enough. Ms. Yamashita, along with her six-year-old sister Sachiko and 10 to 15 other children, were in front of her house, set to walk to the temple. But at 8:15 someone called out, “Look! It’s a B-29!” There was no air-raid siren, though, as was usually the case. Still, the children fled in different directions, seeking shelter in the neighborhood.

Ms. Yamashita picked up Mitsuko, who had just wandered over, and ran into a nearby house, where they dove under the stove. Suddenly there was darkness all around them. When the light gradually returned, she saw that the room was in such disarray that she could hardly find a place to put their feet and they had difficulty escaping.

Her mother, Itsuno, had been asked by a neighbor to switch their work shifts for the war effort, so she was lying down at home when the A-bomb exploded. After the blast, while bleeding from the glass fragments of a wall clock that had pierced her back and bottom, she went to search for Ms. Yamashita, shouting, “Kayoko! Kayoko!” In a state of shock, she was leading two of Sachiko’s friends by the hand. Sachiko had fled to the back door of their house, and a falling tile from the roof struck her head.

With the walls of the house crumbled, they could no longer live there. For about a week, they slept out in the open air on the bank of the Enko River. They saw scores of bodies floating on the water.

After the war, Ms. Yamashita met her husband, Naofumi, 77, while working at the same company. Her mother-in-law was opposed to the marriage, because Ms. Yamashita was an A-bomb survivor, but they overcame such objections and were wed in December 1959.

A few years later, her mother-in-law obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivors Certificate because she had provided aid to the injured in Sakacho, Hiroshima Prefecture in the aftermath of the bombing. “She got the certificate even though she continually criticized me for being a survivor,” Ms. Yamashita recalled. “It was very upsetting.”

She was blessed with one son and two daughters, but in 1990, her first daughter, Sayuri, now 50, developed leukemia. The thought “It’s because she’s the child of an A-bomb survivor” went through her mind. After receiving chemotherapy, Sayuri experienced a full recovery, but three years ago, she was diagnosed with lung cancer and underwent surgery.

Ms. Yamashita herself has suffered cataracts and the removal of a cancerous growth in her thyroid. She must also contend with an incurable condition which causes muscle pain.

“My health is poor,” Ms. Yamashita said, “but I appreciate our life today, where we can get the things we want.” At the same time, she feels there is too much indulgence and so she tries to be frugal. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Volunteer Army Corps: engaged in creating fire lanes and defending the public

The Volunteer Army Corps consisted of groups that were formed in residential communities, or working places, near the end of World War II. They were mainly engaged in efforts to dismantle buildings to create fire lanes in the event of air raids, and defend the public. The corps was made up of men, ages 12 to 65, and women, ages 12 to 45.

In practice, students in junior high schools and girls’ high schools were mobilized for work. Males older than junior high school age were drafted into the military. The corps also included many men and women older than 40. Nominally, it was known as the “volunteer labor service.”

The effort to mobilize the nation’s citizens was launched with the National Mobilization Law, which was legislated in 1938, one year after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The decision to organize the Volunteer Army Corps was made by the government in March 1945.

According to research conducted in 2010 by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the number of people in the Volunteer Army Corps in the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, both those in residential communities and work places, totaled 11,633. Of this number, 4,632 were killed in the atomic bombing.

Teenagers’ Impressions

There should be more opportunities to learn about the A-bombing

It was the first time for Ms. Yamashita to talk about her experience of the atomic bombing to people who weren’t family members. Because the number of A-bomb survivors is decreasing, she decided to share her story with young people who are interested in hearing about her experience.

There might be some survivors who want to hand down their accounts, but they don’t have the opportunity to tell other people. In order to learn about the atomic bombing from many perspectives, we should increase the opportunities for A-bomb survivors to share their stories in newspapers and on TV. (Yuka Ichimura, 16)

The tiniest thing determined one’s fate

I was amazed when I heard that Ms. Yamashita managed to survive because she fled into a nearby house right after spotting the B-29 bomber.

She was only nine years old at the time, but she was so observant and was able to assess the danger and act. Her story made me realize, once again, that the tiniest thing back then could make the difference between life and death. (Miyu Sakata, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Ms. Yamashita told us not only about the suffering caused by the atomic bombing, but also about the hardships of life during and after the war. There was little food to eat, and she felt terribly hungry. She recalled trips to Ninoshima Island and Etajima Island to go food shopping with a big rucksack on her back. In those days, sweet potatoes and pumpkins were the staple foods so now she doesn’t want to eat them. After the war, her family was so poor that she hardly attended junior high; instead, she worked at a cannery and had a job weeding.

After such experiences, the world today seems extravagant to her. “Throwing away rice, cooked or uncooked, is unforgivable,” she said. “It can be made into rice porridge and eaten.” She was strict in teaching her children not to be wasteful. She hopes children today will appreciate their food as well. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on November 13, 2012)

After the bombing, slept on the riverbank, saw bodies in the water

When the atomic bomb exploded, Kayoko Yamashita (nee Munemasa), who was nine years old at the time, held her three-year-old sister Mitsuko and hid under a cooking stove. They were roughly 3 kilometers from the hypocenter and managed to avoid serious injury.

Ms. Yamashita lived in Minamikaniyacho (part of present-day Minami Ward). She would cross the Enko River to attend Hijiyama National School (today’s Hijiyama Elementary School in Minami Ward), but near the end of the war, she went to a classroom at a temple near her home, instead of school. She wasn’t evacuated to the countryside, like many other children, because her family had decided: “If we die, we’ll die together as a family.”

The morning of August 6, 1945 began typically enough. Ms. Yamashita, along with her six-year-old sister Sachiko and 10 to 15 other children, were in front of her house, set to walk to the temple. But at 8:15 someone called out, “Look! It’s a B-29!” There was no air-raid siren, though, as was usually the case. Still, the children fled in different directions, seeking shelter in the neighborhood.

Ms. Yamashita picked up Mitsuko, who had just wandered over, and ran into a nearby house, where they dove under the stove. Suddenly there was darkness all around them. When the light gradually returned, she saw that the room was in such disarray that she could hardly find a place to put their feet and they had difficulty escaping.

Her mother, Itsuno, had been asked by a neighbor to switch their work shifts for the war effort, so she was lying down at home when the A-bomb exploded. After the blast, while bleeding from the glass fragments of a wall clock that had pierced her back and bottom, she went to search for Ms. Yamashita, shouting, “Kayoko! Kayoko!” In a state of shock, she was leading two of Sachiko’s friends by the hand. Sachiko had fled to the back door of their house, and a falling tile from the roof struck her head.

With the walls of the house crumbled, they could no longer live there. For about a week, they slept out in the open air on the bank of the Enko River. They saw scores of bodies floating on the water.

After the war, Ms. Yamashita met her husband, Naofumi, 77, while working at the same company. Her mother-in-law was opposed to the marriage, because Ms. Yamashita was an A-bomb survivor, but they overcame such objections and were wed in December 1959.

A few years later, her mother-in-law obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivors Certificate because she had provided aid to the injured in Sakacho, Hiroshima Prefecture in the aftermath of the bombing. “She got the certificate even though she continually criticized me for being a survivor,” Ms. Yamashita recalled. “It was very upsetting.”

She was blessed with one son and two daughters, but in 1990, her first daughter, Sayuri, now 50, developed leukemia. The thought “It’s because she’s the child of an A-bomb survivor” went through her mind. After receiving chemotherapy, Sayuri experienced a full recovery, but three years ago, she was diagnosed with lung cancer and underwent surgery.

Ms. Yamashita herself has suffered cataracts and the removal of a cancerous growth in her thyroid. She must also contend with an incurable condition which causes muscle pain.

“My health is poor,” Ms. Yamashita said, “but I appreciate our life today, where we can get the things we want.” At the same time, she feels there is too much indulgence and so she tries to be frugal. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Volunteer Army Corps: engaged in creating fire lanes and defending the public

The Volunteer Army Corps consisted of groups that were formed in residential communities, or working places, near the end of World War II. They were mainly engaged in efforts to dismantle buildings to create fire lanes in the event of air raids, and defend the public. The corps was made up of men, ages 12 to 65, and women, ages 12 to 45.

In practice, students in junior high schools and girls’ high schools were mobilized for work. Males older than junior high school age were drafted into the military. The corps also included many men and women older than 40. Nominally, it was known as the “volunteer labor service.”

The effort to mobilize the nation’s citizens was launched with the National Mobilization Law, which was legislated in 1938, one year after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The decision to organize the Volunteer Army Corps was made by the government in March 1945.

According to research conducted in 2010 by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the number of people in the Volunteer Army Corps in the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, both those in residential communities and work places, totaled 11,633. Of this number, 4,632 were killed in the atomic bombing.

Teenagers’ Impressions

There should be more opportunities to learn about the A-bombing

It was the first time for Ms. Yamashita to talk about her experience of the atomic bombing to people who weren’t family members. Because the number of A-bomb survivors is decreasing, she decided to share her story with young people who are interested in hearing about her experience.

There might be some survivors who want to hand down their accounts, but they don’t have the opportunity to tell other people. In order to learn about the atomic bombing from many perspectives, we should increase the opportunities for A-bomb survivors to share their stories in newspapers and on TV. (Yuka Ichimura, 16)

The tiniest thing determined one’s fate

I was amazed when I heard that Ms. Yamashita managed to survive because she fled into a nearby house right after spotting the B-29 bomber.

She was only nine years old at the time, but she was so observant and was able to assess the danger and act. Her story made me realize, once again, that the tiniest thing back then could make the difference between life and death. (Miyu Sakata, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Ms. Yamashita told us not only about the suffering caused by the atomic bombing, but also about the hardships of life during and after the war. There was little food to eat, and she felt terribly hungry. She recalled trips to Ninoshima Island and Etajima Island to go food shopping with a big rucksack on her back. In those days, sweet potatoes and pumpkins were the staple foods so now she doesn’t want to eat them. After the war, her family was so poor that she hardly attended junior high; instead, she worked at a cannery and had a job weeding.

After such experiences, the world today seems extravagant to her. “Throwing away rice, cooked or uncooked, is unforgivable,” she said. “It can be made into rice porridge and eaten.” She was strict in teaching her children not to be wasteful. She hopes children today will appreciate their food as well. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on November 13, 2012)