Kiyoshi Nakata, 83, Akitakata City, Hiroshima

Dec. 25, 2012

Searched for his aunt and other relatives for three days

Horrific scene of bodies along the road burned in his memory

Kiyoshi Nakata, 83, carries some photographs with him along with his A-bomb Survivor Certificate. One photo shows an aunt, Misano Mukai, and her daughter, Yoshiko, the relatives he was living with when the atomic bomb was dropped. Another photo is of an uncle, Kaoru Nishimura. Including these three, Mr. Nakata lost a total of six relatives in the atomic bombing.

In March 1944, Mr. Nakata graduated from the upper course of Yaehigashi National School (present-day Yaehigashi Elementary School), located in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, and began working at the Kure Naval Arsenal as an apprentice. “I was told to make a choice between going to Manchuria [today’s northeastern China] with a group of pioneers to work the land there or working in a munitions factory, so I decided to work at the Kure Naval Arsenal,” he recalled. He wasn’t able to continue his education at higher levels.

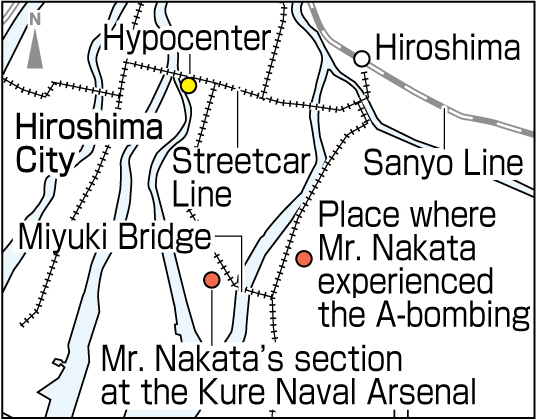

He was assigned to the section working on “electrical experiments” in February 1945. His workplace was on the grounds of the Hiroshima Municipal Second Technical School, located in Sendamachi (part of present-day Naka Ward), so he commuted from his aunt’s house in Danbarashinmachi (now part of Minami Ward).

On August 6, he had finished working the night shift and, at around 8 a.m., left for home by bicycle. He had just crossed the Miyuki Bridge and was cycling through Minamimachi (in today’s Minami Ward), at a place about 2 kilometers from the hypocenter, when suddenly he saw a powerful flash. Wondering if the source could be sparks from a passing streetcar, when he looked back, everything went black. He has no memory of what occurred next. When consciousness returned, he found himself on the ground with his bicycle. But thanks to his “air-raid hood” and steel helmet, he wasn’t injured.

When he arrived home, he discovered that the second story had collapsed. His aunt, her husband, and Yoshiko weren’t there. That day his uncle was scheduled to enter the 11th infantry regiment (in today’s Naka Ward) and so members of his aunt’s family and his uncle’s family, six people in all, had gone to see him off.

For three days, Mr. Nakata searched for his aunt and uncle and other relatives. In the city center, at the Kamiyacho intersection, he came across a charred streetcar and its passengers. Along the roads he saw many more bodies, of soldiers and ordinary citizens. “Even today,” he said, “I can’t forget the horror of those scenes.” At night, he slept in the open, in a grape field in Shinonomecho (part of present-day Minami Ward).

He was unable to locate his six relatives. After the war, he found their names in the register of A-bomb victims that was made by the City of Hiroshima. The register indicates that they were brought to Ninoshima Island, where they died. He was relieved at finally gleaning this information about their fate.

In 1946, he became an apprentice to a carpenter and was involved in architecture in the city of Hiroshima, until nearly the age of 70. Later, he and his wife Shigeko, 83, moved to the city of Akitakata, Shigeko’s hometown. He now cares for apple trees and plum trees while battling angina, numbness in his legs, and a painful spinal cord.

“We shouldn’t put all our emphasis on academic ability,” he said. “I want young people to know about the marvels of manufacturing, too, and make efforts to realize a society without disparity.” For a peaceful world, these are his hopes. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Kure Naval Arsenal: Advanced technology produced the battleship Yamato

The origins of the Kure Naval Arsenal as a naval base date back to 1889 when the Kure Naval District was established in the city of Kure. The arsenal was founded in 1903 when the two undertakings of building ships and manufacturing arms were combined.

After the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the Kure Naval Arsenal built Japan’s first large warship. Because the arsenal boasted advanced technology, it received an order from France to build a destroyer for that nation.

In 1937, when the Sino-Japanese War started, the arsenal began building the biggest battleship of all, dubbed Yamato. Completed on December 16, 1941, just after war in the Pacific broke out, the caliber of the warship’s main guns was 46 centimeters. The arsenal also produced manned torpedoes, called “Kaiten,” a kind of suicide vessel piloted by one man that was designed to attack enemy ships.

During the war, junior high school students and other female students were mobilized to work there. In an Allied air raid that took place on June 22, 1945, the Kure Naval Arsenal was targeted and the area where arms were manufactured was completely destroyed.

After the war, the arsenal was no longer used for a military purpose. Instead, the plants were turned into factories for such companies as IHI Marine United and Nisshin Steel.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I’m glad I can follow my own path

After he graduated, Mr. Nakata was faced with going to Manchuria [today, the northeastern part of China] or working at the Kure Naval Arsenal. I’m so glad that today I have the opportunity to follow my own path in life.

Mr. Nakata told us, “I want people to know about this dreadful thing that happened.” In order to make the world a more peaceful place, we should listen more to the voices of the atomic bomb survivors. (Yuri Ryokai, 15)

I was sad to hear of his anxiety over missing relatives

I was surprised when Mr. Nakata said that English was used in the section where he was working at the Kure Naval Arsenal. I had heard that the use of English was forbidden during the war.

Many of his relatives went missing after the atomic bombing. He felt anxious, he said, because he didn’t know if they were alive or dead until the register of A-bomb victims was released to the public. That made me feel sad. (Miyu Sakata, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

“If someone was absent from work for three days without leave, he was put in handcuffs and charged with desertion, then paraded in front of the other workers.” “During one meal, a worker brought some food to a supervisor, but was falsely accused of an insult and beaten then and there.” “We were forced to do push-ups for 30 minutes or an hour in the hallway of our dormitory.” Such stories sound incredible today, but these are Mr. Nakata’s memories of the time he was working at the Kure Naval Arsenal. The fact that these memories of military life during the war are fading, along with the memories of the atomic bombing, is unfortunate. All of us born after the war should listen and learn from the experiences of those who endured that time in history. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on December 11, 2012)

Horrific scene of bodies along the road burned in his memory

Kiyoshi Nakata, 83, carries some photographs with him along with his A-bomb Survivor Certificate. One photo shows an aunt, Misano Mukai, and her daughter, Yoshiko, the relatives he was living with when the atomic bomb was dropped. Another photo is of an uncle, Kaoru Nishimura. Including these three, Mr. Nakata lost a total of six relatives in the atomic bombing.

In March 1944, Mr. Nakata graduated from the upper course of Yaehigashi National School (present-day Yaehigashi Elementary School), located in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, and began working at the Kure Naval Arsenal as an apprentice. “I was told to make a choice between going to Manchuria [today’s northeastern China] with a group of pioneers to work the land there or working in a munitions factory, so I decided to work at the Kure Naval Arsenal,” he recalled. He wasn’t able to continue his education at higher levels.

He was assigned to the section working on “electrical experiments” in February 1945. His workplace was on the grounds of the Hiroshima Municipal Second Technical School, located in Sendamachi (part of present-day Naka Ward), so he commuted from his aunt’s house in Danbarashinmachi (now part of Minami Ward).

On August 6, he had finished working the night shift and, at around 8 a.m., left for home by bicycle. He had just crossed the Miyuki Bridge and was cycling through Minamimachi (in today’s Minami Ward), at a place about 2 kilometers from the hypocenter, when suddenly he saw a powerful flash. Wondering if the source could be sparks from a passing streetcar, when he looked back, everything went black. He has no memory of what occurred next. When consciousness returned, he found himself on the ground with his bicycle. But thanks to his “air-raid hood” and steel helmet, he wasn’t injured.

When he arrived home, he discovered that the second story had collapsed. His aunt, her husband, and Yoshiko weren’t there. That day his uncle was scheduled to enter the 11th infantry regiment (in today’s Naka Ward) and so members of his aunt’s family and his uncle’s family, six people in all, had gone to see him off.

For three days, Mr. Nakata searched for his aunt and uncle and other relatives. In the city center, at the Kamiyacho intersection, he came across a charred streetcar and its passengers. Along the roads he saw many more bodies, of soldiers and ordinary citizens. “Even today,” he said, “I can’t forget the horror of those scenes.” At night, he slept in the open, in a grape field in Shinonomecho (part of present-day Minami Ward).

He was unable to locate his six relatives. After the war, he found their names in the register of A-bomb victims that was made by the City of Hiroshima. The register indicates that they were brought to Ninoshima Island, where they died. He was relieved at finally gleaning this information about their fate.

In 1946, he became an apprentice to a carpenter and was involved in architecture in the city of Hiroshima, until nearly the age of 70. Later, he and his wife Shigeko, 83, moved to the city of Akitakata, Shigeko’s hometown. He now cares for apple trees and plum trees while battling angina, numbness in his legs, and a painful spinal cord.

“We shouldn’t put all our emphasis on academic ability,” he said. “I want young people to know about the marvels of manufacturing, too, and make efforts to realize a society without disparity.” For a peaceful world, these are his hopes. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Kure Naval Arsenal: Advanced technology produced the battleship Yamato

The origins of the Kure Naval Arsenal as a naval base date back to 1889 when the Kure Naval District was established in the city of Kure. The arsenal was founded in 1903 when the two undertakings of building ships and manufacturing arms were combined.

After the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the Kure Naval Arsenal built Japan’s first large warship. Because the arsenal boasted advanced technology, it received an order from France to build a destroyer for that nation.

In 1937, when the Sino-Japanese War started, the arsenal began building the biggest battleship of all, dubbed Yamato. Completed on December 16, 1941, just after war in the Pacific broke out, the caliber of the warship’s main guns was 46 centimeters. The arsenal also produced manned torpedoes, called “Kaiten,” a kind of suicide vessel piloted by one man that was designed to attack enemy ships.

During the war, junior high school students and other female students were mobilized to work there. In an Allied air raid that took place on June 22, 1945, the Kure Naval Arsenal was targeted and the area where arms were manufactured was completely destroyed.

After the war, the arsenal was no longer used for a military purpose. Instead, the plants were turned into factories for such companies as IHI Marine United and Nisshin Steel.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I’m glad I can follow my own path

After he graduated, Mr. Nakata was faced with going to Manchuria [today, the northeastern part of China] or working at the Kure Naval Arsenal. I’m so glad that today I have the opportunity to follow my own path in life.

Mr. Nakata told us, “I want people to know about this dreadful thing that happened.” In order to make the world a more peaceful place, we should listen more to the voices of the atomic bomb survivors. (Yuri Ryokai, 15)

I was sad to hear of his anxiety over missing relatives

I was surprised when Mr. Nakata said that English was used in the section where he was working at the Kure Naval Arsenal. I had heard that the use of English was forbidden during the war.

Many of his relatives went missing after the atomic bombing. He felt anxious, he said, because he didn’t know if they were alive or dead until the register of A-bomb victims was released to the public. That made me feel sad. (Miyu Sakata, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

“If someone was absent from work for three days without leave, he was put in handcuffs and charged with desertion, then paraded in front of the other workers.” “During one meal, a worker brought some food to a supervisor, but was falsely accused of an insult and beaten then and there.” “We were forced to do push-ups for 30 minutes or an hour in the hallway of our dormitory.” Such stories sound incredible today, but these are Mr. Nakata’s memories of the time he was working at the Kure Naval Arsenal. The fact that these memories of military life during the war are fading, along with the memories of the atomic bombing, is unfortunate. All of us born after the war should listen and learn from the experiences of those who endured that time in history. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on December 11, 2012)