Heitaro Hamada, 82, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Feb. 18, 2013

Shares painful memories of sisters and classmates

Feels a duty not to let these memories fade

Heitaro Hamada, 82, who was a third-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School, located in Naka Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing, lost two sisters and many classmates in the blast. Feeling regret over the fact that they perished, but he survived, he avoided sharing his memories of the bombing for a long time.

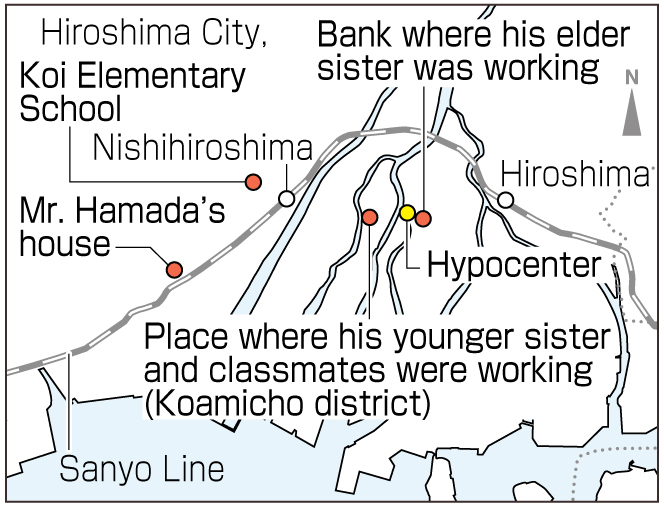

At the start of August 1945, he finally returned to school after suffering from a lung-related illness. But on August 6 he had a high fever and so he missed his mobilized work assignment, which involved dismantling houses to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. He was at home in Furuta (part of present-day Nishi Ward), about 5 kilometers from the hypocenter, when he experienced a great flash and loud boom. The accompanying blast shattered all the windows in his house.

His younger sister, Takako, was 12 years old, in her first year at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School located in Minami Ward). That morning she was helping to dismantle buildings in the Koamicho area (part of today’s Naka Ward). When Mr. Hamada learned from his neighbor that Takako had been brought to Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School in Nishi Ward), he borrowed a two-wheel cart and hurried to the school.

Shouting his sister’s name, he searched for her there. A girl in bare feet then tottered toward him. Her face was swollen and her eyes were mere slits, like threads. He recognized the striped pattern on her ragged monpe (old-fashioned Japanese-style work pants for women).

“Takako?” he said. The girl nodded. His younger sister had suffered severe burns. As they headed for home, she cried out as the cart traveled over the bumpy road: “It hurts! It hurts!” She died, pleading for water, at around 5:00 the following morning, August 7.

His older sister, Teruyo, was 21 years at the time. She was working at a bank in Sarugakucho (in present-day Naka Ward), near the hypocenter. Seven charred bodies were found at that location, but Teruyo could not be identified. Instead of her remains, an A-bombed roof tile—his mother picked it up from the site, he believes—was placed at the family’s Buddhist altar.

Forty-two of Mr. Hamada’s classmates, helping to dismantle houses in the Koamicho district, were killed in the blast. When he ran into surviving members of their families, he would feel sorrow and pain.

Because his father had already died of illness before the atomic bombing, Mr. Hamada and his mother were now on their own. He went on to study at the Hiroshima School of Secondary Education (now Hiroshima University), and became a junior high social studies teacher. Feeling guilty for having survived the blast, he didn’t reveal his A-bomb experience to his students. Finally, after his retirement, when he had passed the age of 70, he began to open up about his past. A teacher friend had told him: “If you don’t share your story on behalf of the victims, their souls won’t rest in peace.”

Mr. Hamada researched the fates of his former classmates and published a book last summer. He felt this was his duty as a survivor, to help prevent the memory of the atomic bombing from fading away.

Appealing to young people, he said, “Please learn about why the atomic bomb was dropped. I hope you will think seriously about what should be done to end war and abolish nuclear weapons.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

The first collection of written accounts on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima was published on August 1, 1946. The title of the book is Izumi: Mitamano maeni sasaguru (Fountain: Offers Made to the Spirits of the Dead).

Thirty-nine students from First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (today’s Kokutaiji High School) and First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School) contributed their accounts to help comfort the souls of third-year students in classroom 35, and other students, who perished in the bombing. Heitaro Hamada, 82, a resident of Nishi Ward, was a third-year student at the time and helped edit the book.

Students of both schools were mobilized to work at the same factory, which produced airplane parts. The students from classroom 35, however, were helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane and were killed in the blast.

The collection of accounts was mimeographed on rough paper. It is a B5-sized book and consists of 67 pages. It expresses such sentiments as “I feel so sad that I lost my friends” and “What does the world know about this?”

Satoru Ubuki, 66, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who has researched the history of the atomic bombing, said, “The book is an expression of mourning, but it also shows the will of the contributors to convey the damage caused by the atomic bombing soon after the war ended.”

The collection of accounts has been preserved at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. A reproduction of the book can be viewed and read there.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to convey the horror of war

Mr. Hamada lost his sisters and classmates when he was the same age as I am now. I think his sadness is probably greater than I can imagine. War steals away our loved ones and can never be excused. I want to hear as many accounts as I can from A-bomb survivors and people who suffered air raids during the war, and convey the horror of war to others. (Takeshi Iwata, 14)

I won’t forget what Mr. Hamada told us

Mr. Hamada lost most of his classmates in the atomic bombing and felt guilt and anguish over having survived. The fact that he could overcome this pain to tell us his story, I’d like to honor that. I won’t forget how he told us to stand up to help prevent war, and I’ll do what I can to live up to these words. (Shoko Kitayama, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

On display in Mr. Hamada’s house are many photos taken at mountains around the world. Mr. Hamada enjoys mountain climbing and has been to mountains in Europe, North America, South America, and Oceania.

During these travels, he has shared his A-bomb experience with the people he encountered. He has been to China more than 20 times, and because he can speak Chinese, he describes his experience in their language and tells them, “I hate war. I hope the world will always be at peace.”

Japan and China share a sad history, with the former Japanese army invading China. However, he has met many Chinese people who view both the Chinese and the people of Hiroshima as victims of war.

For today’s youth, Mr. Hamada offers this message: “Try traveling outside Japan more. You can learn more about the world and also discover the good things about Japan.” (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on January 28, 2013)

Feels a duty not to let these memories fade

Heitaro Hamada, 82, who was a third-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School, located in Naka Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing, lost two sisters and many classmates in the blast. Feeling regret over the fact that they perished, but he survived, he avoided sharing his memories of the bombing for a long time.

At the start of August 1945, he finally returned to school after suffering from a lung-related illness. But on August 6 he had a high fever and so he missed his mobilized work assignment, which involved dismantling houses to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. He was at home in Furuta (part of present-day Nishi Ward), about 5 kilometers from the hypocenter, when he experienced a great flash and loud boom. The accompanying blast shattered all the windows in his house.

His younger sister, Takako, was 12 years old, in her first year at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School located in Minami Ward). That morning she was helping to dismantle buildings in the Koamicho area (part of today’s Naka Ward). When Mr. Hamada learned from his neighbor that Takako had been brought to Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School in Nishi Ward), he borrowed a two-wheel cart and hurried to the school.

Shouting his sister’s name, he searched for her there. A girl in bare feet then tottered toward him. Her face was swollen and her eyes were mere slits, like threads. He recognized the striped pattern on her ragged monpe (old-fashioned Japanese-style work pants for women).

“Takako?” he said. The girl nodded. His younger sister had suffered severe burns. As they headed for home, she cried out as the cart traveled over the bumpy road: “It hurts! It hurts!” She died, pleading for water, at around 5:00 the following morning, August 7.

His older sister, Teruyo, was 21 years at the time. She was working at a bank in Sarugakucho (in present-day Naka Ward), near the hypocenter. Seven charred bodies were found at that location, but Teruyo could not be identified. Instead of her remains, an A-bombed roof tile—his mother picked it up from the site, he believes—was placed at the family’s Buddhist altar.

Forty-two of Mr. Hamada’s classmates, helping to dismantle houses in the Koamicho district, were killed in the blast. When he ran into surviving members of their families, he would feel sorrow and pain.

Because his father had already died of illness before the atomic bombing, Mr. Hamada and his mother were now on their own. He went on to study at the Hiroshima School of Secondary Education (now Hiroshima University), and became a junior high social studies teacher. Feeling guilty for having survived the blast, he didn’t reveal his A-bomb experience to his students. Finally, after his retirement, when he had passed the age of 70, he began to open up about his past. A teacher friend had told him: “If you don’t share your story on behalf of the victims, their souls won’t rest in peace.”

Mr. Hamada researched the fates of his former classmates and published a book last summer. He felt this was his duty as a survivor, to help prevent the memory of the atomic bombing from fading away.

Appealing to young people, he said, “Please learn about why the atomic bomb was dropped. I hope you will think seriously about what should be done to end war and abolish nuclear weapons.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight: Hiroshima’s first collection of A-bomb accounts

The first collection of written accounts on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima was published on August 1, 1946. The title of the book is Izumi: Mitamano maeni sasaguru (Fountain: Offers Made to the Spirits of the Dead).

Thirty-nine students from First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (today’s Kokutaiji High School) and First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School) contributed their accounts to help comfort the souls of third-year students in classroom 35, and other students, who perished in the bombing. Heitaro Hamada, 82, a resident of Nishi Ward, was a third-year student at the time and helped edit the book.

Students of both schools were mobilized to work at the same factory, which produced airplane parts. The students from classroom 35, however, were helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane and were killed in the blast.

The collection of accounts was mimeographed on rough paper. It is a B5-sized book and consists of 67 pages. It expresses such sentiments as “I feel so sad that I lost my friends” and “What does the world know about this?”

Satoru Ubuki, 66, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who has researched the history of the atomic bombing, said, “The book is an expression of mourning, but it also shows the will of the contributors to convey the damage caused by the atomic bombing soon after the war ended.”

The collection of accounts has been preserved at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. A reproduction of the book can be viewed and read there.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to convey the horror of war

Mr. Hamada lost his sisters and classmates when he was the same age as I am now. I think his sadness is probably greater than I can imagine. War steals away our loved ones and can never be excused. I want to hear as many accounts as I can from A-bomb survivors and people who suffered air raids during the war, and convey the horror of war to others. (Takeshi Iwata, 14)

I won’t forget what Mr. Hamada told us

Mr. Hamada lost most of his classmates in the atomic bombing and felt guilt and anguish over having survived. The fact that he could overcome this pain to tell us his story, I’d like to honor that. I won’t forget how he told us to stand up to help prevent war, and I’ll do what I can to live up to these words. (Shoko Kitayama, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

On display in Mr. Hamada’s house are many photos taken at mountains around the world. Mr. Hamada enjoys mountain climbing and has been to mountains in Europe, North America, South America, and Oceania.

During these travels, he has shared his A-bomb experience with the people he encountered. He has been to China more than 20 times, and because he can speak Chinese, he describes his experience in their language and tells them, “I hate war. I hope the world will always be at peace.”

Japan and China share a sad history, with the former Japanese army invading China. However, he has met many Chinese people who view both the Chinese and the people of Hiroshima as victims of war.

For today’s youth, Mr. Hamada offers this message: “Try traveling outside Japan more. You can learn more about the world and also discover the good things about Japan.” (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on January 28, 2013)