Hisako Nakamura, 87, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, and Shizue Frazier, 82, Los Angeles, California

Jul. 23, 2013

Family of 10 survives the A-bombing

Sister marries American soldier, moves to U.S.

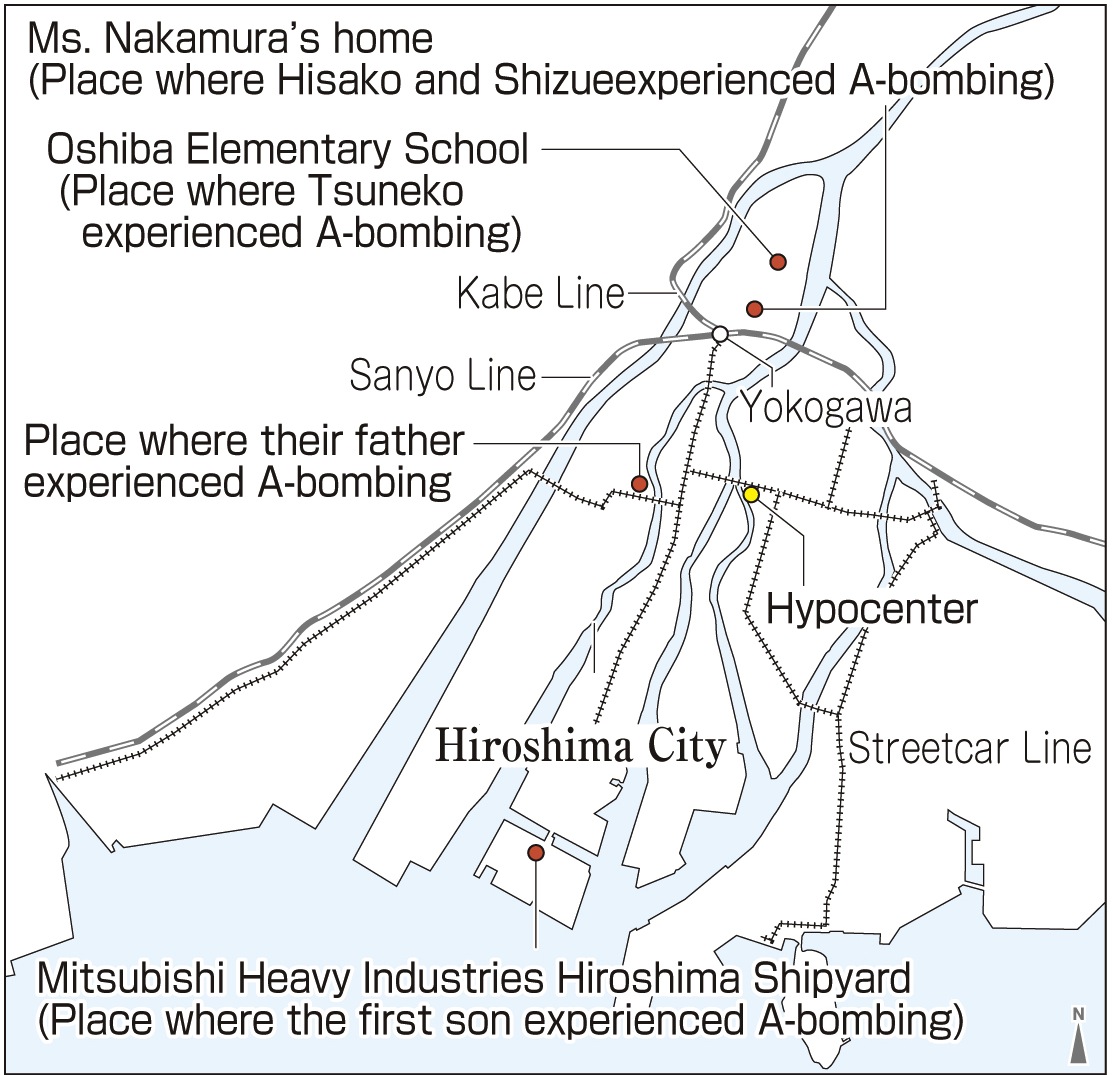

Hisako Nakamura, 87, was the first daughter and Shizue Frazier (nee Nakamura), 82, was the second daughter in a family of eight siblings. On the day of the atomic bombing, seven members of the ten-member family were at home in Misasahonmachi, about 2 kilometers from the hypocenter in today’s Nishi Ward. Including the three other members of the family who were away from home at the time, all ten managed to survive the blast. After the war, Shizue married an American soldier who was stationed at the U.S. military base in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture. She then began a new life in the United States.

Hisako was 19 when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She was set to leave home to commute to work at a branch of the Hiroshima Credit Union (now Hiroshima Shinkin Bank), which was located in the Sakancho district (part of present-day Naka Ward), about half a kilometer from the hypocenter. At the moment she saw the flash, their house began to collapse. Shizue, who was 14, had a stomachache that morning and had stayed home from school. Instead, she went out to find powdered milk for her mother and when she returned from Yokogawa (in Nishi Ward), she saw the bomb’s flash.

Shizue, however, was unable to find her twin sisters, just four months old, who were sleeping under a mosquito net. As fire approached the house, her mother tried to stop her search, telling her that the babies must already have perished when the house collapsed. In spite of her mother’s warning, she waded into the wreckage and spotted something white between a beam and a wall: one of the babies. Then, searching with Hisako, she found the other little girl.

But the bodies of the infants had grown rigid and their eyes only stared blankly. Their mother tore the hem of her kimono and soaked it in water. When she wiped their faces with the wet cloth, their eyes blinked. Looking back at that moment, Shizue smiled and said, “I still remember how happy my mother looked.”

With a nine-year-old brother and four-year-old sister, who both survived at home, the family hurried to Oshiba National School, about 2.4 kilometers from the hypocenter (in present-day Nishi Ward), to pick up 11-year-old Tsuneko. Tsuneko, the third-eldest sister, had been in the school yard for morning assembly when the bomb exploded, and suffered bad burns to her right arm and her legs.

Eight members of the family then fled for Kabe (in today’s Asakita Ward, north of the city center), where an aunt and her family were living. To get to Kabe, they rode in a truck and traveled on foot. At the time of the bombing, the father was on his way to work for the war effort in Koamicho (part of today’s Naka Ward, about 1 kilometer from the hypocenter) and the first son, 17 years old, was mobilized to work at Ebacho, about 4 kilometers from the hypocenter. Both walked home after the blast.

Around three days after the bombing, their father arrived in Kabe. Then, on August 10, the whole family, except for Tsuneko, who had suffered severe burns, and Hisako, who was caring for her, returned to near where their home had once stood, and began living in an air raid shelter. Tsuneko’s burns were treated with a home remedy of crumbled leaves, and she was able to join them around August 20.

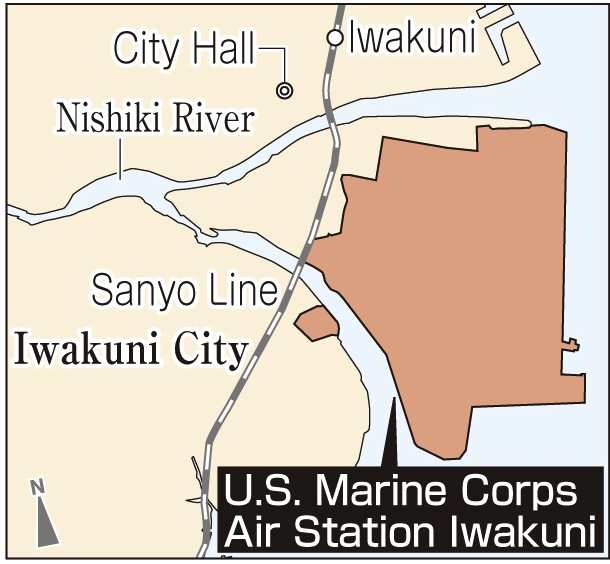

After the war, Shizue worked at the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni as a typist. At the age of 28, she married an American soldier and moved to the United States. Recalling the time, Hisako smiled and said, “Once Shizue had made up her mind to go, no one could stop her. There was nothing we could do.” Shizue said, “The war was fought between nations. It wasn’t a personal thing between individuals. I didn’t experience any discrimination.” When asked, Shizue has spoken about her experience of the atomic bombing. Many people have listened eagerly to her story, some of them telling her how terrible they feel about what happened.

“We don’t really understand politics,” Hisako and Shizue said, “but it’s good if our accounts of the atomic bombing can be helpful, even if just a little.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni: Airport for civilian aircraft, too

At the mouth of the Nishiki River, which flows through the city of Iwakuni, is the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni. Apart from Okinawa, this is the only U.S. Marine Corps air base in Japan. The Japanese Self Defense Force also uses part of the site.

The origins of the base go back to 1938 when the Japanese Imperial Army bought the land from residents and built Iwakuni Airport. The Iwakuni Naval Air Group was then established in July 1940.

One month after the end of World War II, in September 1945, the U.S. Marine Corps came to Iwakuni and was stationed at the base. Troops from the United Kingdom and Australia were subsequently posted at the base, too. When the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty went into effect in April 1952, the British and Australian soldiers withdrew and the base became a U.S. Air Force Base.

In July 1962, it was made a Marine Corps air station. During the Vietnam War, in the 1960s and 1970s, and the Gulf War in the early 1990s, soldiers and supplies were dispatched from Iwakuni for the battlefields.

Meanwhile, the citizens of Iwakuni have endured noise pollution and the risk of accidents. Thus, land was reclaimed to build a new airstrip on the far side of the city, the new airstrip opening in May 2010. From the Naval Air Facility Atsugi in Kanagawa Prefecture, about 60 bombers are expected to shift to the Iwakuni base.

Last December, the Iwakuni Kintaikyo Airport opened at the base, which also functions as an airport for civilian aircraft.

Teenagers’ Impressions

We have to join hands

“Even when nations are at odds, people can be friends,” the sisters told us. Proof of this is found in the fact that many Japanese who live in the A-bombed nation and Americans, from the country that dropped the bomb, later became friends or even married.

We shouldn’t forget our past mistakes, but joining hands is the important thing. (Rei Kamiyasu, 16)

Understand each other as individuals

Some American friends who heard Shizue’s account of the atomic bombing told her that they regretted what happened. I realized that war is a quarrel between nations which involves innocent people.

I think most Americans would like to be friends with the Japanese people. If we can understand each other as individuals, this might be a way of preventing war. (Mei Yoshimoto, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

The entire Nakamura family managed to survive the A-bomb attack. The father, Yaichi, was 45 at the time and he was working for the war effort in Koamicho. He was the only survivor among people present in the Koami district when the bomb exploded. Although he suffered from acute symptoms of radiation exposure, such as bleeding gums, hair loss, and purple spots on his skin, he was able to pull through thanks to his wife, Taeko, who cauterized the skin with moxa for three or four months. Following his recovery, Yaichi lived to the age of 81, finally dying of lung cancer. His wife died at 71, of lung cancer and pancreatic cancer. Their first son, Tamotsu, died of pancreatic cancer, too. The youngest sisters, twins, have had operations, respectively, for uterine cancer and thyroid cancer. Hisako and Shizue worry that these illnesses may have been induced by the atomic bombing.

Shizue was back in Japan for the first time in a year, and stayed at her parents’ house for around two months, where Hisako now lives. She said, “Here in Japan, with the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, I’m able to receive good physical examinations. I’m happy about that.” At the same time, she must face the fact that the long journey from the United States to Japan is getting hard for someone over the age of 80. “This might be my last visit to Hiroshima,” she said. In mid-June, she returned to the United States with the words, “I’m Japanese, but I’ve lived in the U.S. for a long time and it’s my second home now.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

(Originally published on June 24, 2013)

Sister marries American soldier, moves to U.S.

Hisako Nakamura, 87, was the first daughter and Shizue Frazier (nee Nakamura), 82, was the second daughter in a family of eight siblings. On the day of the atomic bombing, seven members of the ten-member family were at home in Misasahonmachi, about 2 kilometers from the hypocenter in today’s Nishi Ward. Including the three other members of the family who were away from home at the time, all ten managed to survive the blast. After the war, Shizue married an American soldier who was stationed at the U.S. military base in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture. She then began a new life in the United States.

Hisako was 19 when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She was set to leave home to commute to work at a branch of the Hiroshima Credit Union (now Hiroshima Shinkin Bank), which was located in the Sakancho district (part of present-day Naka Ward), about half a kilometer from the hypocenter. At the moment she saw the flash, their house began to collapse. Shizue, who was 14, had a stomachache that morning and had stayed home from school. Instead, she went out to find powdered milk for her mother and when she returned from Yokogawa (in Nishi Ward), she saw the bomb’s flash.

Shizue, however, was unable to find her twin sisters, just four months old, who were sleeping under a mosquito net. As fire approached the house, her mother tried to stop her search, telling her that the babies must already have perished when the house collapsed. In spite of her mother’s warning, she waded into the wreckage and spotted something white between a beam and a wall: one of the babies. Then, searching with Hisako, she found the other little girl.

But the bodies of the infants had grown rigid and their eyes only stared blankly. Their mother tore the hem of her kimono and soaked it in water. When she wiped their faces with the wet cloth, their eyes blinked. Looking back at that moment, Shizue smiled and said, “I still remember how happy my mother looked.”

With a nine-year-old brother and four-year-old sister, who both survived at home, the family hurried to Oshiba National School, about 2.4 kilometers from the hypocenter (in present-day Nishi Ward), to pick up 11-year-old Tsuneko. Tsuneko, the third-eldest sister, had been in the school yard for morning assembly when the bomb exploded, and suffered bad burns to her right arm and her legs.

Eight members of the family then fled for Kabe (in today’s Asakita Ward, north of the city center), where an aunt and her family were living. To get to Kabe, they rode in a truck and traveled on foot. At the time of the bombing, the father was on his way to work for the war effort in Koamicho (part of today’s Naka Ward, about 1 kilometer from the hypocenter) and the first son, 17 years old, was mobilized to work at Ebacho, about 4 kilometers from the hypocenter. Both walked home after the blast.

Around three days after the bombing, their father arrived in Kabe. Then, on August 10, the whole family, except for Tsuneko, who had suffered severe burns, and Hisako, who was caring for her, returned to near where their home had once stood, and began living in an air raid shelter. Tsuneko’s burns were treated with a home remedy of crumbled leaves, and she was able to join them around August 20.

After the war, Shizue worked at the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni as a typist. At the age of 28, she married an American soldier and moved to the United States. Recalling the time, Hisako smiled and said, “Once Shizue had made up her mind to go, no one could stop her. There was nothing we could do.” Shizue said, “The war was fought between nations. It wasn’t a personal thing between individuals. I didn’t experience any discrimination.” When asked, Shizue has spoken about her experience of the atomic bombing. Many people have listened eagerly to her story, some of them telling her how terrible they feel about what happened.

“We don’t really understand politics,” Hisako and Shizue said, “but it’s good if our accounts of the atomic bombing can be helpful, even if just a little.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni: Airport for civilian aircraft, too

At the mouth of the Nishiki River, which flows through the city of Iwakuni, is the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni. Apart from Okinawa, this is the only U.S. Marine Corps air base in Japan. The Japanese Self Defense Force also uses part of the site.

The origins of the base go back to 1938 when the Japanese Imperial Army bought the land from residents and built Iwakuni Airport. The Iwakuni Naval Air Group was then established in July 1940.

One month after the end of World War II, in September 1945, the U.S. Marine Corps came to Iwakuni and was stationed at the base. Troops from the United Kingdom and Australia were subsequently posted at the base, too. When the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty went into effect in April 1952, the British and Australian soldiers withdrew and the base became a U.S. Air Force Base.

In July 1962, it was made a Marine Corps air station. During the Vietnam War, in the 1960s and 1970s, and the Gulf War in the early 1990s, soldiers and supplies were dispatched from Iwakuni for the battlefields.

Meanwhile, the citizens of Iwakuni have endured noise pollution and the risk of accidents. Thus, land was reclaimed to build a new airstrip on the far side of the city, the new airstrip opening in May 2010. From the Naval Air Facility Atsugi in Kanagawa Prefecture, about 60 bombers are expected to shift to the Iwakuni base.

Last December, the Iwakuni Kintaikyo Airport opened at the base, which also functions as an airport for civilian aircraft.

Teenagers’ Impressions

We have to join hands

“Even when nations are at odds, people can be friends,” the sisters told us. Proof of this is found in the fact that many Japanese who live in the A-bombed nation and Americans, from the country that dropped the bomb, later became friends or even married.

We shouldn’t forget our past mistakes, but joining hands is the important thing. (Rei Kamiyasu, 16)

Understand each other as individuals

Some American friends who heard Shizue’s account of the atomic bombing told her that they regretted what happened. I realized that war is a quarrel between nations which involves innocent people.

I think most Americans would like to be friends with the Japanese people. If we can understand each other as individuals, this might be a way of preventing war. (Mei Yoshimoto, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

The entire Nakamura family managed to survive the A-bomb attack. The father, Yaichi, was 45 at the time and he was working for the war effort in Koamicho. He was the only survivor among people present in the Koami district when the bomb exploded. Although he suffered from acute symptoms of radiation exposure, such as bleeding gums, hair loss, and purple spots on his skin, he was able to pull through thanks to his wife, Taeko, who cauterized the skin with moxa for three or four months. Following his recovery, Yaichi lived to the age of 81, finally dying of lung cancer. His wife died at 71, of lung cancer and pancreatic cancer. Their first son, Tamotsu, died of pancreatic cancer, too. The youngest sisters, twins, have had operations, respectively, for uterine cancer and thyroid cancer. Hisako and Shizue worry that these illnesses may have been induced by the atomic bombing.

Shizue was back in Japan for the first time in a year, and stayed at her parents’ house for around two months, where Hisako now lives. She said, “Here in Japan, with the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, I’m able to receive good physical examinations. I’m happy about that.” At the same time, she must face the fact that the long journey from the United States to Japan is getting hard for someone over the age of 80. “This might be my last visit to Hiroshima,” she said. In mid-June, she returned to the United States with the words, “I’m Japanese, but I’ve lived in the U.S. for a long time and it’s my second home now.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

(Originally published on June 24, 2013)