Terue Toda, 81, Hatsukaichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture

Oct. 15, 2013

Feeling regret that she couldn’t save friends

Finally saw her responsibility to speak out

For Terue Toda (nee Hiura), 81, the atomic bombing was a memory she didn’t want others to bring up. She has lived for 68 years since the bombing, blaming herself for the loss of friends who were with her that day.

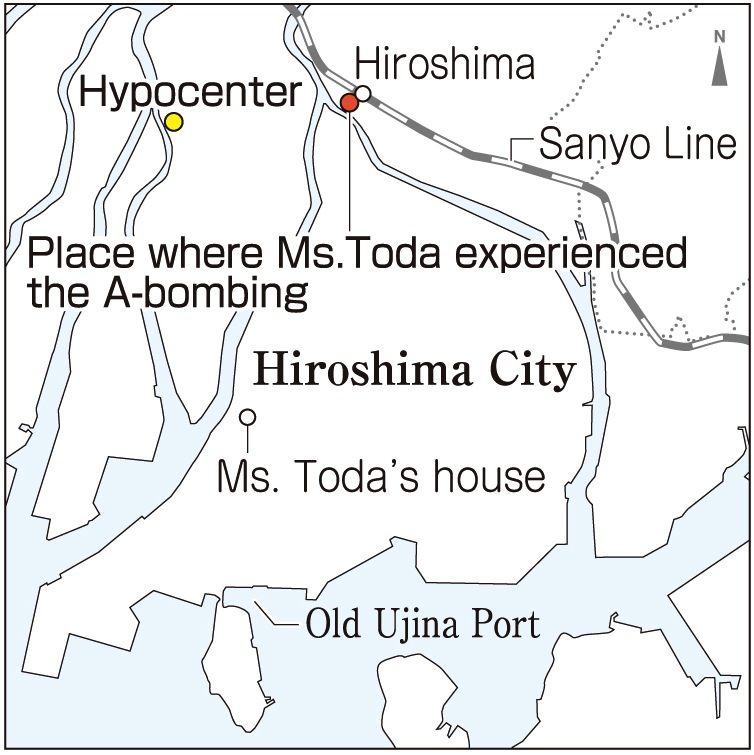

Ms. Toda was born in Ujina-cho, part of present-day Minami Ward. The old Ujina Port, where many soldiers sailed away to war, was located near her house, and she often went there to see them off. As she watched the soldiers march by, their eyes fixed forward, she found them frightening. With two older brothers dying in battle, her childhood was engulfed by the war.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Toda was 13 years old and a second-year student at the Third National School (now, Midorimachi Junior High School). Since the spring of 1945, she had been receiving training to undertake work with the National Railway which involved communications. Girls of this age were being called from in and out of the city to replace men who had become soldiers.

On the morning of August 6, Ms. Toda went to a meeting spot near Hiroshima Station, in today’s Minami Ward, to wait for all the students to assemble. The location was about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. While they were waiting, a friend was braiding Ms. Toda’s hair. Then someone shouted, “Look! B-29 bombers!” At that instant, Ms. Toda saw a flash and lost consciousness as she was blown through the air by the blast.

She came to at the sound of voices crying and shouting things like “Help me, mother!” and “It’s so hot!” She then crept out from under the wreckage of the building. The friend who had been braiding her hair was on the ground, stretched out and facing the sky, her eyes open. Other friends were groaning from under the debris. But she was just a child and had no strength to help them escape. In desperation, she fled from the approaching fire.

Around 7 o’clock that evening she finally arrived home in Ujina-cho. Her house was wrecked, so she and her mother, who had also survived, were forced to sleep out in the open air for some time. During this period she suffered from symptoms of acute radiation sickness, including vomiting, diarrhea, and hair loss.

After the war, she graduated from Kokutaiji High School, located in Naka Ward. She then took a clerical job at Funairi High School, also in Naka Ward, and became a preschool teacher because she wanted to help children in need. At the age of 27, she got married and raised three daughters while working in clerical jobs at an elementary school and junior high school.

After keeping her memories of the atomic bombing shut away in her mind, around 20 years ago she began to talk about her experience. While taking part in the activities of the Young Women’s Christian Association, she saw a recitation play on the atomic bombing by members of the YWCA of Kumamoto. Stunned by the performance, she thought, “It’s irresponsible that I, an A-bomb survivor, am not speaking out about the atomic bombing. I want to find the courage to convey the importance of peace.”

Since then, she has been sharing her experience of the bombing with students visiting Hiroshima on school trips. She appeals to students: “Everyone’s life is meaningful. I want you to cherish your life as long as you live. And I want you to cherish the lives of others, too.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Ujina Port: Dispatching soldiers and supplies

The construction of Ujina Port, located in the southern part of the city, was begun in 1884 by then Hiroshima Governor Sadaaki Senda (1836-1908). He felt that a good port should be created to help develop the city of Hiroshima.

Despite a number of difficulties, which included local opposition over damage to oyster and seaweed production, and a destructive storm which hit the embankment, the port was completed in 1889. While the port was being built, it is said that Mr. Senda covered the shortfall for the costs from his own pocket.

The port played an important role in several wars. When the First Sino-Japanese War broke out in August 1894, soldiers and supplies were dispatched to the front lines from the Ujina Port. That same month, a railway from the port to Hiroshima Station, the Ujina Line, was constructed in only 17 days. (The Ujina Line was discontinued in 1986.) Later, many soldiers left for battle from this port during the Russo-Japanese War and World War II.

In 1932, the name of the port was changed to Hiroshima Port. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, many wounded were taken from the port to a temporary relief station on Ninoshima Island, part of present-day Minami Ward.

Today’s passenger terminal is located west of the original building.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Make a world without war

The remains of Ms. Toda’s two brothers, who died in battle, were never returned to the family. Instead, her mother received only a wooden box, which she embraced in tears. I’ve never had such a sad experience, but I imagine it was really hard for her to go on. When I grow up, I want to help make a world without war, where conflicts can be resolved by talking them out. (Kota Ueda,10)

Create peace around us

Ms. Toda regrets leaving her friends that day when she fled. However, it’s because of survivors like her, who could overcome the deaths of loved ones and the discrimination of being an A-bomb survivor, and work together, that the city of Hiroshima was successfully rebuilt. In order to create a peaceful world, the next step is to end the conflict around us. (Nanase Shode,14)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

I took a walk around the Ujina-cho district (part of today’s Minami Ward), where Ms. Toda was born and raised. The experience taught me a lot about Hiroshima’s history as a military city.

Yoshinori Masuda, 75, formerly a principal at Ujina Elementary School, is well versed in the history of Ujina. As he guided me around the old Ujina Port area, Mr. Masuda told me, “Many soldiers went off to war from here and never returned to step on Japanese soil again.” In Ujina Wharf Park, we saw the remains of the old military pier.

Along the old Ujina Line (now defunct), which linked the old Ujina Port and its dispatches of soldiers to Hiroshima’s main train station, were a number of military facilities.

The remains of an army food depot, which stored food for soldiers and military horses, can be seen near Ujina Wharf Park. Sengyo Temple, an A-bombed building, was a site where the remains of soldiers who died in the war were returned to their bereaved families.

The fact that Hiroshima was an important military city at the time is one reason it was attacked with the atomic bomb. Mr. Masuda explained, “Ujina lifted the development of Hiroshima when the war broke out. On the other hand, Hiroshima suffered the destruction of the atomic bomb because of it. I hope people will visit Hiroshima and learn about the history of the city.” (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on September 23, 2013)

Finally saw her responsibility to speak out

For Terue Toda (nee Hiura), 81, the atomic bombing was a memory she didn’t want others to bring up. She has lived for 68 years since the bombing, blaming herself for the loss of friends who were with her that day.

Ms. Toda was born in Ujina-cho, part of present-day Minami Ward. The old Ujina Port, where many soldiers sailed away to war, was located near her house, and she often went there to see them off. As she watched the soldiers march by, their eyes fixed forward, she found them frightening. With two older brothers dying in battle, her childhood was engulfed by the war.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Toda was 13 years old and a second-year student at the Third National School (now, Midorimachi Junior High School). Since the spring of 1945, she had been receiving training to undertake work with the National Railway which involved communications. Girls of this age were being called from in and out of the city to replace men who had become soldiers.

On the morning of August 6, Ms. Toda went to a meeting spot near Hiroshima Station, in today’s Minami Ward, to wait for all the students to assemble. The location was about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. While they were waiting, a friend was braiding Ms. Toda’s hair. Then someone shouted, “Look! B-29 bombers!” At that instant, Ms. Toda saw a flash and lost consciousness as she was blown through the air by the blast.

She came to at the sound of voices crying and shouting things like “Help me, mother!” and “It’s so hot!” She then crept out from under the wreckage of the building. The friend who had been braiding her hair was on the ground, stretched out and facing the sky, her eyes open. Other friends were groaning from under the debris. But she was just a child and had no strength to help them escape. In desperation, she fled from the approaching fire.

Around 7 o’clock that evening she finally arrived home in Ujina-cho. Her house was wrecked, so she and her mother, who had also survived, were forced to sleep out in the open air for some time. During this period she suffered from symptoms of acute radiation sickness, including vomiting, diarrhea, and hair loss.

After the war, she graduated from Kokutaiji High School, located in Naka Ward. She then took a clerical job at Funairi High School, also in Naka Ward, and became a preschool teacher because she wanted to help children in need. At the age of 27, she got married and raised three daughters while working in clerical jobs at an elementary school and junior high school.

After keeping her memories of the atomic bombing shut away in her mind, around 20 years ago she began to talk about her experience. While taking part in the activities of the Young Women’s Christian Association, she saw a recitation play on the atomic bombing by members of the YWCA of Kumamoto. Stunned by the performance, she thought, “It’s irresponsible that I, an A-bomb survivor, am not speaking out about the atomic bombing. I want to find the courage to convey the importance of peace.”

Since then, she has been sharing her experience of the bombing with students visiting Hiroshima on school trips. She appeals to students: “Everyone’s life is meaningful. I want you to cherish your life as long as you live. And I want you to cherish the lives of others, too.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Ujina Port: Dispatching soldiers and supplies

The construction of Ujina Port, located in the southern part of the city, was begun in 1884 by then Hiroshima Governor Sadaaki Senda (1836-1908). He felt that a good port should be created to help develop the city of Hiroshima.

Despite a number of difficulties, which included local opposition over damage to oyster and seaweed production, and a destructive storm which hit the embankment, the port was completed in 1889. While the port was being built, it is said that Mr. Senda covered the shortfall for the costs from his own pocket.

The port played an important role in several wars. When the First Sino-Japanese War broke out in August 1894, soldiers and supplies were dispatched to the front lines from the Ujina Port. That same month, a railway from the port to Hiroshima Station, the Ujina Line, was constructed in only 17 days. (The Ujina Line was discontinued in 1986.) Later, many soldiers left for battle from this port during the Russo-Japanese War and World War II.

In 1932, the name of the port was changed to Hiroshima Port. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, many wounded were taken from the port to a temporary relief station on Ninoshima Island, part of present-day Minami Ward.

Today’s passenger terminal is located west of the original building.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Make a world without war

The remains of Ms. Toda’s two brothers, who died in battle, were never returned to the family. Instead, her mother received only a wooden box, which she embraced in tears. I’ve never had such a sad experience, but I imagine it was really hard for her to go on. When I grow up, I want to help make a world without war, where conflicts can be resolved by talking them out. (Kota Ueda,10)

Create peace around us

Ms. Toda regrets leaving her friends that day when she fled. However, it’s because of survivors like her, who could overcome the deaths of loved ones and the discrimination of being an A-bomb survivor, and work together, that the city of Hiroshima was successfully rebuilt. In order to create a peaceful world, the next step is to end the conflict around us. (Nanase Shode,14)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

I took a walk around the Ujina-cho district (part of today’s Minami Ward), where Ms. Toda was born and raised. The experience taught me a lot about Hiroshima’s history as a military city.

Yoshinori Masuda, 75, formerly a principal at Ujina Elementary School, is well versed in the history of Ujina. As he guided me around the old Ujina Port area, Mr. Masuda told me, “Many soldiers went off to war from here and never returned to step on Japanese soil again.” In Ujina Wharf Park, we saw the remains of the old military pier.

Along the old Ujina Line (now defunct), which linked the old Ujina Port and its dispatches of soldiers to Hiroshima’s main train station, were a number of military facilities.

The remains of an army food depot, which stored food for soldiers and military horses, can be seen near Ujina Wharf Park. Sengyo Temple, an A-bombed building, was a site where the remains of soldiers who died in the war were returned to their bereaved families.

The fact that Hiroshima was an important military city at the time is one reason it was attacked with the atomic bomb. Mr. Masuda explained, “Ujina lifted the development of Hiroshima when the war broke out. On the other hand, Hiroshima suffered the destruction of the atomic bomb because of it. I hope people will visit Hiroshima and learn about the history of the city.” (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on September 23, 2013)