Sadae Oda, 89, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Feb. 18, 2014

Horrific scenes at Hiroshima Station

“Peace means a world where there’s give-and-take”

She couldn’t stop crying as she watched the A-bombed wounded being carried into Bingotokaichi Station (today’s Miyoshi Station in the city of Miyoshi). “How did this happen?” she wondered. For Ms. Sadae Oda (nee Kamei), 89, the sorrow and horror she felt when she saw such scenes at the age of 20 are still seared into her mind. She confesses: “Almost 70 years have passed since then, and I want to forget it, but I can’t.”

Due to a dearth of male workers, a result of the war effort, Ms. Oda was working as a conductor on Japanese National Railway trains running on the Geibi and Fukuen Lines. At 9:45 p.m. on August 5, 1945, she boarded the last train departing from Hiroshima Station, located in present-day Minami Ward, and returned to Miyoshi. The next morning, while she was sleeping in a boarding house in front of Bingotokaichi Station, she was awakened by a flash through the curtains and a sound like fireworks exploding.

A short while later, the train engineer who had returned with her to Miyoshi the night before came to her room. “Hiroshima has been bombed, and Fukuya department store is in flames,” he told her. “We’ll run a shuttle to Yaga Station.” (Yaga Station is located in today’s Higashi Ward.) Ms. Oda then quickly tied up her hair and hurried to Bingotokaichi Station.

At the station, a train pulled in with nearly 100 passengers jammed into each car. They were in a sorry state as they emerged from the train, their hair disheveled, their clothes in tatters, some carried and lined up on the platform like luggage. When Ms. Oda asked where they wanted to go, at times she received no response at all.

On August 7, she manned a train to Hiroshima, her first trip to the city since the atomic bombing. Walking from Yaga Station to Hiroshima Station, in one spot she saw that the train tracks had warped up and down, like heaving waves. It was an astonishing sight. At Hiroshima Station, the end of platform 7, for the Geibi Line, was charred black. Ms. Oda was told that the bodies of the people who died on the platform were doused with oil and burned. Seeing this horrific transformation of the city, in just a single day, she wept on and on.

After the war, men returned from the battlefields and Ms. Oda left her job at the railway in November 1945. Her parents told her not to tell others that she had experienced the bombing, since she could face prejudice and discrimination. In 1949, when she got married, questions about this largely didn’t arise.

However, after giving birth to her first child in 1950, she felt so fatigued that she was unable to even stand. When she went to the hospital, she was diagnosed with swelling in her thyroid gland. Looking back at that time, she says, “Thinking about it now, it could have been connected to the atomic bombing.”

For her, says Ms. Oda, “Peace means a world where there’s give-and-take. If we’re only concerned about winning, then we always have to knock others down.” She wants young people to cherish their lives, saying, “Talking to each other is so important.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

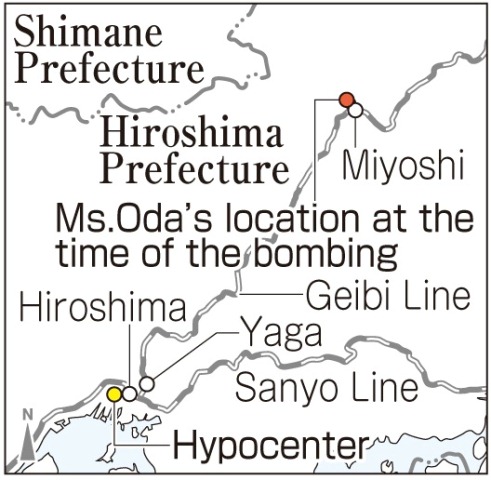

Geibi Line: Trains brought survivors north of the A-bombed city

The Geibi Line runs between Hiroshima Station (in Minami Ward) and Bicchukojiro (in the city of Niimi). It links the five cities of Hiroshima, Akitakata, Miyoshi, Shobara, and Niimi, with 44 stations and 159.1 kilometers of track.

The origins of the Geibi Line can be traced back to the Taisho period (1912-1926) when the Geibi Tetsudo, a private railway, began operating between Hiroshima and Bingoshobara (the city of Shobara). In the early Showa period (1926-1989), along with the opening of a line between Bingoshobara and Bicchukojiro by the Japanese National Railway, the early Geibi Line was nationalized and officially became the Geibi Line in 1937.

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, the Geibi Line ran a shuttle service from Yaga Station (in Higashi Ward), the station next to Hiroshima Station. According to such sources as the “Miyoshi City History” and the “Tojo Town History,” survivors of the A-bomb blast were brought by train to outlying stations in Mukaihara, Yoshidaguchi, Kotachi, Miyoshi, Shobara, Tojo, and other locations. The “Miyoshi City History” mentions the fact that, because it was well known that military and navy hospitals had been evacuated to several places in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture before the bombing, many victims headed for the northbound Geibi Line.

Trains to Hiroshima Station began running again on August 9, three days after the bombing.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Children suffer without mercy

Ms. Oda told us that she saw a girl’s shoe floating in the water in the moat surrounding Hiroshima Castle. I can’t forget this description, that a girl jumped into the moat seeking water and then when her lifeless body was pulled out, only her shoe was left. The atomic bomb made even little children suffer, without mercy, and again made me feel that nuclear weapons must be abolished. (Shiho Fujii, 12)

Wounds to the mind

When Ms. Oda was describing the terrible scenes she saw, she repeated, “For the longest time, I’ve wondered how such a thing could happen.” I realized again that the atomic bomb left not only injuries to the body, but wounds to the mind as well. However, although it’s probably very painful for her to recount her experience, she told us, “I feel more at peace after sharing my story with you.” I was pleased to hear those words. (Saaya Teranishi, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

On August 4, 1945, Ms. Oda came upon a mother holding baby girl in the train stopped at Bingotokaichi Station (today’s Miyoshi Station). The woman asked Ms. Oda if they could spend the night on the train because they had nowhere to stay. Spending the night on the train wasn’t permitted, though, so Ms. Oda brought the mother and baby to her boarding house in Miyoshi. The woman told her that they had come from the town of Takano (now Shobara City) and were headed to Hiroshima to meet her husband, who was a soldier.

At the time, only those holding the proper identification, such as military personnel, were able to ride the train, but Ms. Oda enabled them to board on August 5 and told the woman: “If you want to return home soon, let’s go back together tonight.” That night, she found them on the platform, but the woman said that her husband was away from his unit that day and would be coming back the next morning. Because she wanted to see her husband, she had decided to spend the night at the station instead of taking the return train. As a result, the mother and her baby died in the bombing.

With lingering regret, Ms. Oda said, “I should have taken them home, even if it meant forcing them to go.”

More fortunately, on August 5, she saw another woman with a three-year-old child and a baby on her back who had just missed the last train on the Geibi Line. The train had already begun to move, but she helped pull them up onto the train. The woman’s husband was killed in the bombing, but the mother and her two children managed to avoid the same fate.

After the war, once her children were grown, she began learning to make handicrafts using beads. At around the age of 40, she started teaching a class in this as well. She sold her handicrafts for many years, until about a year ago.

Ms. Oda told us, “I want to cherish each day, not take life for granted.” Her words were inspiring. (Rie Nii)

(Originally Published on January 27, 2014)

“Peace means a world where there’s give-and-take”

She couldn’t stop crying as she watched the A-bombed wounded being carried into Bingotokaichi Station (today’s Miyoshi Station in the city of Miyoshi). “How did this happen?” she wondered. For Ms. Sadae Oda (nee Kamei), 89, the sorrow and horror she felt when she saw such scenes at the age of 20 are still seared into her mind. She confesses: “Almost 70 years have passed since then, and I want to forget it, but I can’t.”

Due to a dearth of male workers, a result of the war effort, Ms. Oda was working as a conductor on Japanese National Railway trains running on the Geibi and Fukuen Lines. At 9:45 p.m. on August 5, 1945, she boarded the last train departing from Hiroshima Station, located in present-day Minami Ward, and returned to Miyoshi. The next morning, while she was sleeping in a boarding house in front of Bingotokaichi Station, she was awakened by a flash through the curtains and a sound like fireworks exploding.

A short while later, the train engineer who had returned with her to Miyoshi the night before came to her room. “Hiroshima has been bombed, and Fukuya department store is in flames,” he told her. “We’ll run a shuttle to Yaga Station.” (Yaga Station is located in today’s Higashi Ward.) Ms. Oda then quickly tied up her hair and hurried to Bingotokaichi Station.

At the station, a train pulled in with nearly 100 passengers jammed into each car. They were in a sorry state as they emerged from the train, their hair disheveled, their clothes in tatters, some carried and lined up on the platform like luggage. When Ms. Oda asked where they wanted to go, at times she received no response at all.

On August 7, she manned a train to Hiroshima, her first trip to the city since the atomic bombing. Walking from Yaga Station to Hiroshima Station, in one spot she saw that the train tracks had warped up and down, like heaving waves. It was an astonishing sight. At Hiroshima Station, the end of platform 7, for the Geibi Line, was charred black. Ms. Oda was told that the bodies of the people who died on the platform were doused with oil and burned. Seeing this horrific transformation of the city, in just a single day, she wept on and on.

After the war, men returned from the battlefields and Ms. Oda left her job at the railway in November 1945. Her parents told her not to tell others that she had experienced the bombing, since she could face prejudice and discrimination. In 1949, when she got married, questions about this largely didn’t arise.

However, after giving birth to her first child in 1950, she felt so fatigued that she was unable to even stand. When she went to the hospital, she was diagnosed with swelling in her thyroid gland. Looking back at that time, she says, “Thinking about it now, it could have been connected to the atomic bombing.”

For her, says Ms. Oda, “Peace means a world where there’s give-and-take. If we’re only concerned about winning, then we always have to knock others down.” She wants young people to cherish their lives, saying, “Talking to each other is so important.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Geibi Line: Trains brought survivors north of the A-bombed city

The Geibi Line runs between Hiroshima Station (in Minami Ward) and Bicchukojiro (in the city of Niimi). It links the five cities of Hiroshima, Akitakata, Miyoshi, Shobara, and Niimi, with 44 stations and 159.1 kilometers of track.

The origins of the Geibi Line can be traced back to the Taisho period (1912-1926) when the Geibi Tetsudo, a private railway, began operating between Hiroshima and Bingoshobara (the city of Shobara). In the early Showa period (1926-1989), along with the opening of a line between Bingoshobara and Bicchukojiro by the Japanese National Railway, the early Geibi Line was nationalized and officially became the Geibi Line in 1937.

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, the Geibi Line ran a shuttle service from Yaga Station (in Higashi Ward), the station next to Hiroshima Station. According to such sources as the “Miyoshi City History” and the “Tojo Town History,” survivors of the A-bomb blast were brought by train to outlying stations in Mukaihara, Yoshidaguchi, Kotachi, Miyoshi, Shobara, Tojo, and other locations. The “Miyoshi City History” mentions the fact that, because it was well known that military and navy hospitals had been evacuated to several places in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture before the bombing, many victims headed for the northbound Geibi Line.

Trains to Hiroshima Station began running again on August 9, three days after the bombing.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Children suffer without mercy

Ms. Oda told us that she saw a girl’s shoe floating in the water in the moat surrounding Hiroshima Castle. I can’t forget this description, that a girl jumped into the moat seeking water and then when her lifeless body was pulled out, only her shoe was left. The atomic bomb made even little children suffer, without mercy, and again made me feel that nuclear weapons must be abolished. (Shiho Fujii, 12)

Wounds to the mind

When Ms. Oda was describing the terrible scenes she saw, she repeated, “For the longest time, I’ve wondered how such a thing could happen.” I realized again that the atomic bomb left not only injuries to the body, but wounds to the mind as well. However, although it’s probably very painful for her to recount her experience, she told us, “I feel more at peace after sharing my story with you.” I was pleased to hear those words. (Saaya Teranishi, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

On August 4, 1945, Ms. Oda came upon a mother holding baby girl in the train stopped at Bingotokaichi Station (today’s Miyoshi Station). The woman asked Ms. Oda if they could spend the night on the train because they had nowhere to stay. Spending the night on the train wasn’t permitted, though, so Ms. Oda brought the mother and baby to her boarding house in Miyoshi. The woman told her that they had come from the town of Takano (now Shobara City) and were headed to Hiroshima to meet her husband, who was a soldier.

At the time, only those holding the proper identification, such as military personnel, were able to ride the train, but Ms. Oda enabled them to board on August 5 and told the woman: “If you want to return home soon, let’s go back together tonight.” That night, she found them on the platform, but the woman said that her husband was away from his unit that day and would be coming back the next morning. Because she wanted to see her husband, she had decided to spend the night at the station instead of taking the return train. As a result, the mother and her baby died in the bombing.

With lingering regret, Ms. Oda said, “I should have taken them home, even if it meant forcing them to go.”

More fortunately, on August 5, she saw another woman with a three-year-old child and a baby on her back who had just missed the last train on the Geibi Line. The train had already begun to move, but she helped pull them up onto the train. The woman’s husband was killed in the bombing, but the mother and her two children managed to avoid the same fate.

After the war, once her children were grown, she began learning to make handicrafts using beads. At around the age of 40, she started teaching a class in this as well. She sold her handicrafts for many years, until about a year ago.

Ms. Oda told us, “I want to cherish each day, not take life for granted.” Her words were inspiring. (Rie Nii)

(Originally Published on January 27, 2014)