History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 1, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

Relief efforts and assistance activities

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995. Since that time, the main subject of this article, Floyd Schmoe, passed away on April 20, 2001 at the age of 105. One of the houses that Mr. Schmoe built for A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima still exists today.

“Finally, like a sorcerer's apprentice, we may practice our magic without knowing how to stop it.”

In 1945, British playwright George Bernard Shaw, upon hearing the news that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima, made this critical remark in “The Times of London.”

In line with Mr. Shaw's prophecy, nearly 50 years has passed and the human race remains under the spell of the nuclear age, a time fraught with the danger of man's annihilation. The A-bombed city of Hiroshima, once blanketed in debris and the stench of death, has been reborn as a modern city with tall buildings standing side by side. The reconstruction of the city could be considered a ray of hope for the inhabitants of this nuclear age.

Hiroshima, I believe, has become the city it is today, a city of peace, through the support of people of conscience around the world, fellow human beings who were shocked by the inhumanity of the atomic bombing, along with the tireless efforts made by Hiroshima citizens.

As a first step in our reflections on the road that Hiroshima has traveled over the past 50 years, the Chugoku Shimbun will trace the news coverage that has conveyed the horrific reality of the atomic bombing as well as the people who took up the challenge of seeking ways to break the spell of the nuclear age through their relief efforts and aid activities for Hiroshima citizens.

Houses quietly built in the razed city of Hiroshima

A one-story house, an uncommon structure these days, stands in the Eba district in downtown Hiroshima. The cracked walls and blackened pillars reveal the passage of time. This house is the only one that still exists among the 20 “Hiroshima Houses” that were built in three locations in the city over a span of four years, starting in 1949, by an American forestry scientist and his supporters.

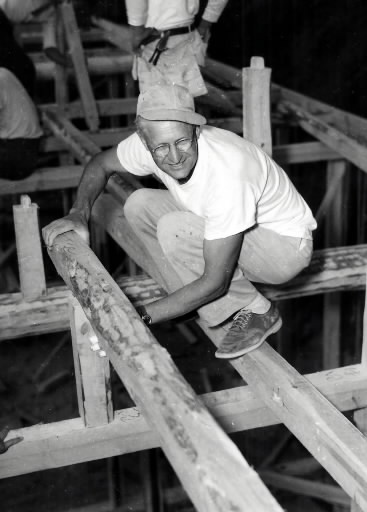

The scientist's name is Floyd Schmoe. Mr. Schmoe is a Quaker, a tradition which believes in providing service to others based on a strict commitment to pacifism. He was a conscientious objector during World War I, refusing to take up arms. During World War II, he devoted his time to fighting discrimination against minorities, including efforts to oppose the forced internment of Japanese-Americans. After Hiroshima was reduced to ashes in the atomic bombing, Mr. Schmoe traveled across the ocean to Japan and quietly built houses for A-bomb survivors. Fifty-four years old at the time, he described his efforts as a way to ease his own heartache over the tragedy.

Mr. Schmoe once said that the very moment he heard the news of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, while at the office of an organization of peace volunteers in Seattle, Washington, he felt as if the bomb had been dropped on him. He was shocked that human beings had sunk to such a base level. His pangs of conscience sparked fear for humanity's future.

Aki Kurose, 69, a second-generation Japanese-American and a resident of Seattle, worked with Mr. Schmoe at the organization of peace volunteers. Ms. Kurose said that Mr. Schmoe's gentle countenance was replaced by a mournful expression and that he said, over and over, how ashamed he was of the attack. He quickly sent a telegram of protest to the president of the United States. Ms. Kurose added that Mr. Schmoe was so livid that she felt unable to approach him at the time.

That very day Mr. Schmoe decided to build houses in Japan as a volunteer, harking back to his experience taking part in relief efforts for refugees in Europe. He traveled across the United States, calling for donations of at least one dollar. Along the way, Mr. Schmoe encountered a five-year-old boy who offered to donate his allowance, saying that he would give up buying candy for a year. To earn his travel expenses for the trip to Japan, Mr. Schmoe worked part-time and his wife, Ruth, worked for a cannery.

On August 4, 1949, Mr. Schmoe stepped onto a platform at Hiroshima station with 4,000 dollars that had been raised through the goodwill of sympathetic donors. Baggage in his third-class carriage was being casually tossed out the window of the train, quickly creating a mound of baggage on the platform. Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai and others ran up to Mr. Schmoe from some distance away, wiping sweat from their brows. The welcoming party had been waiting for the second-class carriage because people of the time took it for granted that Americans rode second-class.

The group led by Mr. Schmoe included Emery Andrews, a clergyman; Daisy Davis, a university lecturer; and Ruth Jenkins, an elementary school teacher. The four members of this group, who shook hands with the fully-attired mayor, were in clothes slightly dirtied with dust due to the long journey. Shy smiles passed over their faces as a camera flashed.

The group settled in Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church and served as volunteers at Hiroshimakinen Hospital while waiting for the construction work to begin. One day, Mr. Schmoe took Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto's oldest daughter Koko, then 4, to Hiroshima Castle and the pair climbed to the top of a stone wall. Below them sprawled shacks in the glow of evening. Mr. Schmoe felt touched by the strength shown by the survivors of the bombing, now rising from the ashes. He was holding Koko in his arms and he gave her a squeeze.

Koko is now active in peace efforts from the city of Suita in Osaka Prefecture. Recalling that moment with Mr. Schmoe, she said: “The warmth of his body may have helped define my life from that point on.” Just prior to the Gulf War, she flew to Baghdad to make a direct appeal to Saddam Hussein, then the Iraqi president, to avoid war.

On the 12th day after their arrival in Hiroshima, the group began to build houses. Under the blazing sun, they loaded lumber onto a two-wheeled cart and traveled to the Minami area, about two kilometers from the church. The procession, which included student volunteers from Tokyo and Hiroshima, drew the attention of residents. Mr. Schmoe winked at people who gave the group suspicious looks. The mood then softened and children paraded behind them with glee.

In “Japan Journey,” the book Mr. Schmoe wrote about his experience, there is a passage which describes three bright boys who were about 12 years old and worked alongside him. One of the boys was Yukihiko Ikeda, 57, former director general of the Defense Agency and a member of the House of Representatives from Hiroshima’s second constituency. Mr. Ikeda recalled: “We ate watermelon together at home. When I asked him how Americans ate watermelons, he said, ‘Like this,’ and took a big bite. He was someone who could easily steal your heart.”

About two months later, four houses were finished. A stone lantern inscribed with the words “That There May Be Peace” was placed in the garden. The number of people who hoped to live in the houses grew to as many as 3,800. On October 1, a ceremony was held to hand over the houses to the selected residents. At the request of Mr. Schmoe, the name of the houses, as printed on the invitations, was changed from “Minami Schmoe Housing” to “Minami Peace Housing.”

Standing before Mayor Hamai and others, Mr. Schmoe spoke calmly, saying that the houses were a visible expression of love. The heartache he had felt since the atomic bombing was finally eased, he said.

Mr. Schmoe visited Hiroshima several times after that and built a total of 20 houses and meeting places. More than 500 families lived in these houses. Afterwards, too, he continued to manifest his belief in the importance of peace actions, leading him to build more houses in South Korea after the ceasefire of the Korean War and in the Middle East.

Striving quietly to build homes for former “enemies” in a former “enemy country,” Mr. Schmoe etched a precious love for humanity in the devastated city of Hiroshima, giving great hope to the citizens of Hiroshima as they devoted themselves to the task of reconstructing the city. To honor his exceptional support, the City of Hiroshima presented Mr. Schmoe with the title of Honorary Citizen of Hiroshima in 1983.

Today, Mr. Schmoe is in good health in the city of Seattle. His remaining years are being spent in the home of his daughter Ruthanna. As long as his health permits, he will continue to pay visits to the peace park that he has built there. The park, which he constructed with the prize money he received when he was given the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize in 1988, features a bronze statue of Sadako Sasaki holding a paper crane, like the one standing in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, and a stone lantern with traces of the atomic bombing that was presented to him by Mayor Hamai.

Mr. Schmoe, a humanist and a forestry scientist who has long cared deeply about the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, will turn 100 this year. The last “Hiroshima House,” evidence of the humanity he lavished on Hiroshima, is slated to be demolished in the near future in line with future plans for the city.

Brief history: Goodwill from abroad supports reconstruction

Assistance from abroad also supported the reconstruction of Hiroshima. On September 8, 1945, in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, Dr. Marcel Junod, head of the Japan delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross, entered Hiroshima with 15 tons of medical supplies. It is said that these medical supplies were distributed to hospitals and first-aid stations that had run out of medicine, enabling the lives of tens of thousands to be saved.

In his memoir, Dr. Junod wrote that the tragic deaths of scores of people, passing away in severe pain, was not a catastrophe of Hiroshima and Nagasaki alone and that each one of us might suffer such a fate. Amid the debris, which he equated with the disaster that once befell Pompeii, Italy, Dr. Junod touched the truth that human beings cannot coexist with nuclear weapons.

Full-scale assistance activities for Hiroshima began in 1947 when “Hiroshima,” a report by John Hersey, was widely read. Such stories as Catholic soldiers stationed in five prefectures of the Chugoku region donating 60,000 dollars and a boy who handed 15 cents he had earned through delivering newspapers to someone traveling to Japan made a deep impression on Hiroshima residents.

Among the international community, people of Japanese descent who lived overseas were especially eager to extend a helping hand, as a large number of them were originally from Hiroshima. An organization promoting assistance for the reconstruction of Hiroshima, whose core membership consisted of people from Hiroshima in a Los Angeles-based association, donated more than 3,000 dollars to the Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry in 1948, as their first donation, despite facing hardships resulting from their forced internment during the war. Then, in 1950, this group donated 5 million yen, in Japanese currency, to the City of Hiroshima. Another group in Hawaii launched a fundraising campaign in 1948 and the following year donated 112,000 dollars to the City of Hiroshima and Hiroshima Prefecture.

Groups of people originally from Hiroshima Prefecture who were living in Brazil, Peru, and Argentina, among other nations, sent a series of donations from 1947 to 1951. These donations were used to develop welfare facilities, including homes for senior citizens and housing for fatherless families, as well as to provide for war orphans. The Hiroshima Children's Library, a round building with glass walls that was designed by Kenzo Tange, an associate professor at the University of Tokyo, and built with donations from Los Angeles, drew attention as a symbol of goodwill.

Religious figures, quick to raise their voices to protest the inhumanity of the atomic bombs, also stood tall in helping to provide the city with assistance. One example of these efforts was the construction of the Memorial Cathedral for World Peace in the Nobori-cho section of downtown Hiroshima. The project was proposed by Father Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle, an A-bomb survivor who served at a Catholic church in Nobori-cho.

The cathedral, completed in 1954, cost 80 million yen to construct, with 60 million yen of this amount collected overseas. In addition, the cathedral received a variety of gifts from abroad, including a pipe organ from the City of Cologne in the former West Germany, four church bells from Bochum, a tabernacle from the City of Bonn, a baptistery from the City of Aachen, the bronze front doors from the City of Dusseldorf, and the main altar, made of marble, from Belgium. A message from Pope John Paul, praising the cathedral as a symbol of the path toward peace, was conveyed at the ceremony to inaugurate the new church.

The history of Hiroshima's reconstruction was also shaped by the large number of international residents who used their personal funds to support the relief efforts. These included Norman Cousins, the editor-in-chief of the U.S. “Saturday Review of Literature,” who made earnest efforts for the “moral adoption campaign” involving A-bomb orphans and the campaign which brought “A-bomb maidens” to the United States for medical treatment, as well as Ira and Edita Morris, both writers, who built the “Hiroshima House of Rest” for A-bomb survivors.

(Originally published on January 22, 1995)