History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 1, Article 2)

Aug. 1, 2012

News coverage of the atomic bombing

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

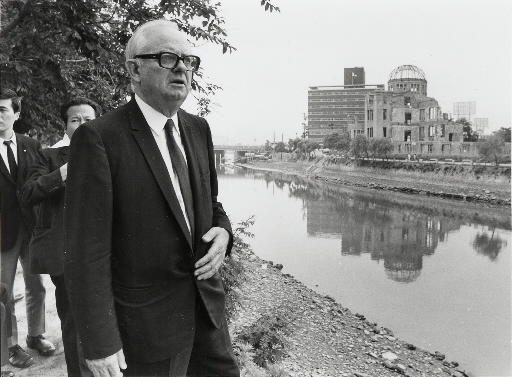

Note: This article was originally published in 1995. Since that time, the main subject of this article, Floyd Schmoe, passed away on April 20, 2001 at the age of 105. One of the houses that Mr. Schmoe built for A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima still exists today.

“Finally, like a sorcerer's apprentice, we may practice our magic without knowing how to stop it.”

In 1945, British playwright George Bernard Shaw, upon hearing the news that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima, made this critical remark in “The Times of London.”

In line with Mr. Shaw's prophecy, nearly 50 years has passed and the human race remains under the spell of the nuclear age, a time fraught with the danger of man's annihilation. The A-bombed city of Hiroshima, once blanketed in debris and the stench of death, has been reborn as a modern city with tall buildings standing side by side. The reconstruction of the city could be considered a ray of hope for the inhabitants of this nuclear age.

Hiroshima, I believe, has become the city it is today, a city of peace, through the support of people of conscience around the world, fellow human beings who were shocked by the inhumanity of the atomic bombing, along with the tireless efforts made by Hiroshima citizens.

As a first step in our reflections on the road that Hiroshima has traveled over the past 50 years, the Chugoku Shimbun will trace the news coverage that has conveyed the horrific reality of the atomic bombing as well as the people who took up the challenge of seeking ways to break the spell of the nuclear age through their relief efforts and aid activities for Hiroshima citizens.

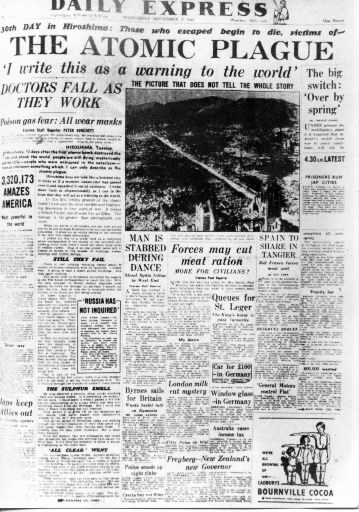

Report from Hiroshima: “a warning to the world”

“I write this as a warning to the world. In Hiroshima, 30 days after the first atomic bomb destroyed the city and shook the world, people are still dying, mysteriously and horribly—people who were uninjured in the cataclysm—from an unknown something which I can only describe as the atomic plague.”

On September 5, 1945, an article that led with these words appeared on the front page of The Daily Express, a British newspaper. It was dispatched from Japan by journalist Wilfred Burchett. Mr. Burchett's exposé, from the perspective of a reporter from an Allied nation setting foot in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, revealed the horror of radiation to the world.

Figures in religion and science, among others, had already spoken out in the aftermath of the bombing, condemning the atomic bomb as inhumane. One letter, sent by such critics to the San Francisco Chronicle, a U.S. newspaper, held that the United States could no longer brand others war criminals with the same impunity. However, these denunciations were based on ethical considerations, not a direct experience of the disaster zone. Mr. Burchett's report legitimized this criticism.

Mr. Burchett caught wind of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima while in Okinawa. He was standing in line in a mess hall for U.S. forces, waiting for a hamburger, when an excited voice on the radio announced that the United States had dropped a new type of bomb. According to his book, entitled “Hiroshima Today,” the instant an officer told him that it was an atomic bomb, he had in mind that if he covered Japan, Hiroshima would be the first site he would visit.

On September 2, when other reporters were rushing to cover the ceremony of Japan's surrender aboard the USS Missouri, Mr. Burchett was on a train bound for Hiroshima. Enduring openly hostile looks in the crowded passenger carriage, he arrived in Hiroshima the following morning.

In the city the stench of death hung in the air. People wandered through the ruins like ghosts, like they had lost their souls. At Hiroshima Teishin Hospital, Mr. Burchett heard a shocking story:

“Some people come down with A-bomb disease even when they simply enter the city after the bombing to look for the remains of family members. Those with severe symptoms of the disease are dying.”

In the rivers that run through the city, Mr. Burchett saw scores of fish floating upside-down, their white bellies exposed. Columns of smoke rose here and there from cremations of the dead. Sitting amid the debris, he tapped away on his typewriter.

His report on Hiroshima raised the ire of the military authorities of the Allied nations, who were concerned about growing calls for the “international control of atomic bombs.” On September 5, the day United Press (now, UPI) also reported that many people in Hiroshima were dying, one after another, due to radiation, the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) delivered an official statement that, as of September 6, 1945, no one in the city was suffering from radiation sickness. An article headlined “No Radioactivity in Hiroshima Ruin,” written by W.H. Lawrence, also appeared in The New York Times.

Mr. Lawrence was the only science journalist who was a witness to the A-bomb experiment at the Trinity Site in New Mexico. In fact, he arrived in Hiroshima by military plane, several hours after Mr. Burchett. However, Mr. Lawrence was focused on the might of the atomic bomb and he conducted no interviews with Hiroshima citizens nor did he gather information from hospitals in the city.

In the end, Mr. Burchett's report from Hiroshima, because of the very fact that it was an incisive piece which cut to the heart of the brutality of nuclear weapons, was engulfed in the shadowy tide of international politics and drowned out by the post-war euphoria celebrating the advent of peace. What's more, Mr. Burchett was forced into the hospital for health examinations of his own and, during his stay there, his camera, which contained images of the catastrophe that had befallen the city of Hiroshima, was stolen.

Hersey follows in Burchett's footsteps

The following year, in the late August of 1946, newsstands in New York bristled with excitement as customer after customer bought The New Yorker, a weekly magazine. Every page of that issue was devoted to a long article entitled “Hiroshima,” written by journalist John Hersey and based on interviews with six A-bomb survivors that he had conducted in Hiroshima in May.

For the first time, the voices of human beings who had been beneath the flash of the atomic bomb were being heard. The New Yorker sold out its run of 300,000 copies in a single day, and the article was reprinted in more than 100 newspapers. The Hiroshima “boom” lasted two years, and included a dramatization of Mr. Hersey's report by one television network. Albert Einstein is said to have stated that the report should not be called “popular”; rather, it raised a humanitarian issue. He apparently purchased 2,000 copies and gave them to his acquaintances.

According to an opinion poll conducted by the U.S. Gallup Organization in 1947, 38 percent of the respondents said that the development of the atomic bomb was “evil,” almost double the percentage, 17 percent, of those who gave the same answer in 1945. The “warning to the world” that Mr. Burchett had issued was finally reaching people's hearts through Mr. Hersey's effort.

With the Cold War between United States and the Soviet Union intensifying, news coverage of this kind, coupled with sympathy toward Hiroshima, stirred a slew of action expressing opposition to atomic bombs. Such action eventually produced momentum for the peace movement, ranging from the “No More Hiroshimas” campaign to the campaigns against atomic and hydrogen bombs.

Originator of the phrase “No More Hiroshimas”

Rutherford Poats, a special correspondent in Tokyo for the United Press (now, UPI), coined the phrase “No More Hiroshimas,” which has become a universal expression of warning for the nuclear age.

In March of 1948, Mr. Poats conducted an interview in Tokyo with Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto of the Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church, who was then making efforts to hold a world peace conference for religious leaders in Hiroshima. In his English translation, Mr. Poats rendered Reverend Tanimoto's Japanese words “I don't want to see the tragedy of Hiroshima recur anywhere else in the world” into “No More Hiroshimas,” and included this phrase in the text of a telegram. The phrase then appeared in newspapers in the United States, as well as in “The Pacific Stars and Stripes,” a newspaper for U.S. troops stationed in Japan.

Afterwards, Alfred Parker, a church custodian in the U.S. city of Oakland, California, began to use the expression as a slogan for the peace movement, and use of the phrase quickly spread across the world. In an interview with the Chugoku Shimbun, Mr. Poats said that he had altered the expression “No More Wars,” which was chanted in Europe following World War I.

Some believe that Mr. Burchett coined the phrase, and a number of books on the atomic bombing offer this explanation. But the expression “No More Hiroshimas” is not found in Mr. Burchett's initial report from Hiroshima. During a return visit to the city, Mr. Burchett himself denied this contention.

The fear of a barren Hiroshima

The fear that “nothing would grow in Hiroshima for the next 70 (or 75) years,” which spread across the city in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, had its origin in a statement made by Dr. Harold Jacobson, who was involved in the project to produce the atomic bomb. His remark appeared in the Washington Post on August 8, 1945.

Dr. Jacobson, however, retracted his own words on the day the newspaper article was published. According to Satoru Ubuki, associate professor at the Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, the FBI pressured Dr. Jacobson to make this retraction.

In Japan, several newspapers, including the August 23 edition of the Mainichi Shimbun, reported the notion that Hiroshima would be barren for seven decades as evidence of the atomic bomb's brutality, bringing the bottomless horror of the A-bomb damage to a wide audience.

An investigative team that was dispatched to Hiroshima in September by the GHQ and the Manhattan Project, which had built the atomic bomb, refuted the idea that the city would remain barren for the next 70 years. However, the GHQ exercised strict control over news coverage related to the A-bomb damage and ordered the Asahi Shimbun, on September 18, to suspend publication for 48 hours. On September 19 the GHQ then issued a press code on the Japanese media.

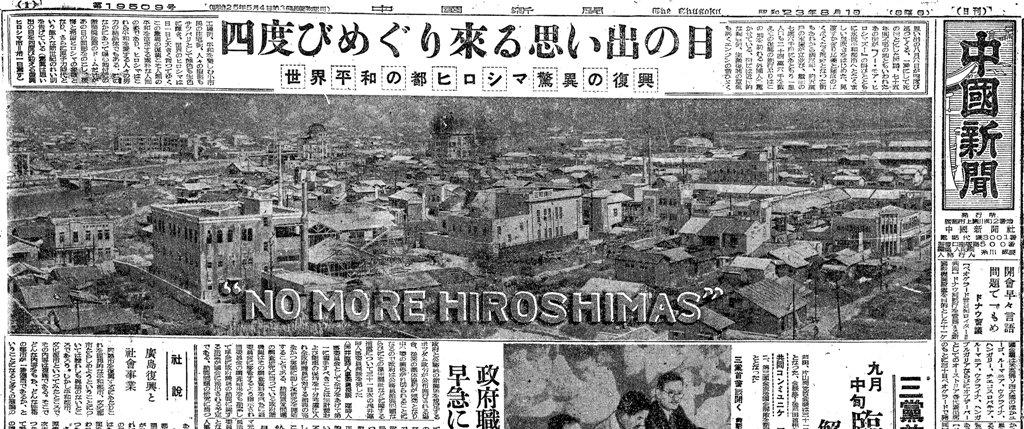

Article in the Chugoku Shimbun on August 1, 1948

NO MORE HIROSHIMAS

On August 1, 1948, three years after the atomic bombing, the front page of the Chugoku Shimbun trumpeted the English headline “NO MORE HIROSHIMAS” with a photo splashed across the full width of the page that depicted reconstruction work in Hiroshima. At that time, the “No More Hiroshimas Campaign”—a forerunner of the campaigns against atomic and hydrogen bombs—had just reached its peak, and the passion of Hiroshima citizens for reconstruction and their wishes for peace burst forth from the newspaper. Here is the English translation of that article:

August 6, stirring a host of memories of the atomic bombing, is looming for the fourth time. On August 6, 1945, Hiroshima was instantly transformed into a place of death. Despite warnings that the city would be barren for 75 years, Hiroshima has returned vigorously to life to become a city of lasting peace, led by the cry “No More Hiroshimas.”

A full three years have already passed since the city became a vast, desolate plain of ruins and weeds as far as the eye could see. About 50,000 houses now stand side by side, just shy of the 76,000 homes that existed before the war. The population numbers 246,000 and the state of progress in the city's reconstruction is a great surprise to foreign visitors.

Hiroshima now boasts modern shopping streets, an industrial zone with the high-spirited roars of engines announcing the revival of production, and residential areas with citizens savoring this time of peace. People are neatly dressed and their faces are bright with life, while Hiroshima, a city of peace for the world, grows larger day by day.

This astonishing rebirth is the fruit of humble human beings who desire peace for all humankind. Through their efforts, these peace-loving people have transformed Hiroshima into a city of peace. Only the dome of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, near the hypocenter, remains a reminder of the day of the atomic bombing. The ruins of this building have become a symbol of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, a symbol of remorse and yet hope, while signifying the dawn of the great new era of the atomic age.

(Originally published on January 22, 1995)