History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 3, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law

by Yoshifumi Fukushima, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

The path leading to the reconstruction of the city of Hiroshima, which had been devastated by the atomic bomb, involved long days of seeking the financial resources and the mental support needed for the task. During this period of hardship, the “Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law” offered a ray of hope both materially and psychologically. The law, which pledges “the pursuit of genuine and lasting peace” and guarantees that the central government shoulder a portion of the funds for reconstruction, has served as the foundation for the city's revival. While subsequent post-war generations have been increasingly unaware of the existence of this law, the eyes of the man who drafted the law remain fixed on Hiroshima.

One of the major projects in the reconstruction of the city was the effort to redevelop the Motomachi district. The so-called “A-bomb slum,” a residential area that was formerly crowded with homes, now boasts multistory apartment buildings. However, a new urban problem, the aging of the population in this downtown area, is growing at a quickening pace.

There were fervent efforts behind the enactment of the law which enabled Hiroshima to be reborn into a city of peace. Following this, the shadow of an aging population grew to loom over the major reconstruction project that was intended to move Hiroshima beyond the post-war era. The Chugoku Shimbun will examine the background of the city’s reconstruction.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Plan imbued with quest for lasting peace

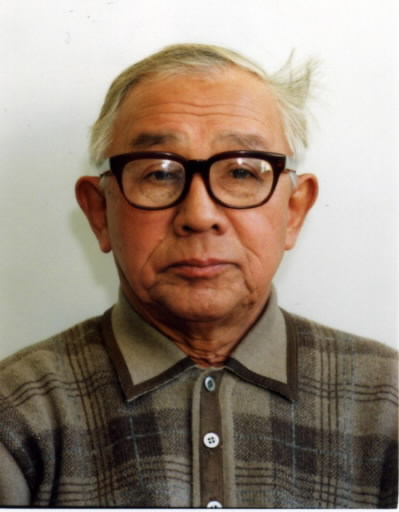

Tadashi Teramitsu drafts bill of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law

Tadashi Teramitsu sat up all night writing the first draft of a new law, completing the draft in one sitting. On that winter morning, as the first light of day began to color the window of his official residence, the original shape of the law, comprised of a preamble and nine provisions, was formed. It was a draft of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, which served as the foundation for the reconstruction of Hiroshima following the atomic bombing. “I thought I had to do something about Hiroshima,” said Mr. Teramitsu, 86, who lives in a quiet residential area in Setagaya Ward, Tokyo, as he calmly recounted the days of 46 years ago.

On February 13, 1949, Tsukasa Nitoguri, chair of the Hiroshima City Council, visited Mr. Teramitsu's office, accompanied by an Upper House member. Mr. Teramitsu was then director general of the Proceedings Department of the Upper House. Mr. Nitoguri told him: “Four years have passed since the atomic bombing. Though we have continued to petition the Diet for assistance with the reconstruction of Hiroshima, the government won't act even when our petitions are accepted. I would really be grateful for your guidance.” Mr. Nitoguri, who was meeting Mr. Teramitsu for the first time, bowed his head.

In the wake of the devastation of the atomic bombing, the City of Hiroshima had been petitioning the Diet for funds to move forward with its reconstruction efforts, as well as campaigning to acquire former military sites from the Japanese government, but it was having little success. The city's prospects for the future seemed bleak. Mr. Teramitsu, a native of Hiroshima who was familiar with Diet proceedings and knowledgeable about the law, caught the attention of the A-bombed city. Mr. Teramitsu replied: “A petition may make you feel better, but it's ineffective. The only way forward is to create a law which incorporates the intentions of Hiroshima citizens and binds the hands of the government.” Mr. Teramitsu knew that, in line with the new Constitution and Diet law in the post-war period, a special law for local autonomies could be created through a proposal put forward by parliamentarians.

The next day, Mr. Teramitsu received a formal commission from a Diet Member representing Hiroshima Prefecture, among others, to prepare a draft. However, there were difficult obstacles. Hiroshima was, of course, the first city in history to be attacked with an atomic bomb, but preserving a balance of support between Hiroshima and other parts of the country damaged in the war was a delicate point. Moreover, the United States had dropped the atomic bomb and the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) would not permit legislation that focused on the reconstruction of Hiroshima. At the time, all bills needed prior approval from the GHQ before they were submitted to the Diet.

Mr. Teramitsu thought: “Then, let us pursue the reconstruction of Hiroshima with a loftier aim, beyond the idea of mere 'reconstruction.'” The idea led him to the expression “peace for all time,” which was included in Japan's new Constitution. With advice from the Legislative Bureau of the House of Councilors, Mr. Teramitsu polished the draft again and again over a period of roughly three months, producing five drafts.

Mr. Teramitsu was a graduate of the former Hiroshima High School and then attended the University of Tokyo. He joined the Ministry of Justice and became a career bureaucrat. Though he had had little contact with his hometown, he was unable to forget the scene in front of Hiroshima station after stepping off an overnight train three months after the atomic bombing. There were no buildings in sight and the stench of death still hung in the air. The utter destruction of the area, which allowed an unbroken view as far away as Ninoshima Island, staggered him. This experience fueled his desire to prepare a bill to aid Hiroshima.

The draft consisted of seven provisions. The first article states, “It shall be the object of the present law to provide for the construction of the city of Hiroshima as a peace memorial city to symbolize the human ideal of sincere pursuit of genuine and lasting peace.” Mr. Teramitsu stressed, “This is the essence of the law.” His thoughts behind this legislation were: “The law will not only enable Hiroshima to recover from the war damage, but it will promote the idea of 'lasting peace,' on which all human beings have fixed their minds. The central government will cooperate fully in the 'creation' of a city of peace, and the citizens of Hiroshima will also exert themselves to that end.” The draft of the law clearly captured the aims that the city had sought in its petitioning of the government and the contents proved persuasive to the eyes of the GHQ.

When the final draft of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law was completed, Nagasaki sought to join Hiroshima and receive benefits under the law. As history unfolded, however, the law for Hiroshima preserved its uniqueness, leading Nagasaki to create the Nagasaki International Cultural City Construction Law. After a number of twists and turns, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, a special law, was passed at the Lower House on May 10, 1949 and on May 11 at the Upper House. On July 7, the law was put to a referendum, the first referendum held in Japan. The law was then promulgated on August 6, four years after the atomic bombing, with the approval of 91 percent of the voters who had cast a total of approximately 78,000 votes. Only six months had passed since Mr. Teramitsu began to draft the law. Compared to the speed of the campaign seeking the reconstruction of the city up to that point, the law was enacted in a flash.

At the end of November of 1994, a folder of documents was handed to parliamentarians at the Diet. It was a report describing the progress of projects that were underway in 14 cities nationwide under the City Construction Special Acts, including the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law. The prime minister is obliged to report on these projects to the Diet once a year. This demonstrates that the law is still in effect now, even after the City of Hiroshima has become an ordinance-designated city.

For post-war Hiroshima, which lacked independent sources of revenue, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction law took on great significance in that the law enabled the city to obtain funds for the reconstruction effort. For five years, starting in the fiscal year of 1950, the city received a subsidy of about 920 million yen from the central government, mainly for peace memorial facilities and land readjustment. Though the amount of the subsidy did not cover the total cost of the city's reconstruction projects, it still brought enormous benefits to the city. Under the law, 19 government-owned plots of land with a total area of 34 hectares were reallocated to the city as land for public use. The late Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai compared this law to a “mallet of luck.”

However, no land has been reallocated for the past 28 years, since the reallocation of the site for the municipal high school in 1967, because Hiroshima's finances have grown stronger and the city is now solvent. The “Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Plan” remains the name for city planning efforts and progress in this regard is still reported to the Diet. However, Hiroshima is granted no preferential treatment and the formula for financial assistance is the same as it is for other cities. Arguments to abolish the law have even been made three times in a Diet debate on administrative and financial reform.

“This law may be about to die now,” Mr. Teramitsu said. “But I don't want to let it die.” It is a law that went as far as a referendum in order to go into effect. Although the city may have realized the goal of reconstruction, Mr. Teramitsu has become concerned with respect to the extent the spirit of the law is being pursued. “Now that we have endured the difficult times, I hope that people will grasp and reflect again on the basic principle of the law,” he said.

Mr. Teramitsu, who works as a university lecturer while also practicing law, never fails to speak about the basis of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law when he lectures on the Constitution.

“Hiroshima is not simply a city of remembrance, a city to view traces of the atomic bombing,” Mr. Teramitsu said. “If the city can be a place that inspires thoughts of peace in people when they come here, that would be wonderful.” He wonders, though, if the city is fulfilling this mission. In 1970, the city, in the basic concept it laid out, formulated the idea of presenting Hiroshima as an “international city of peace culture.” Mr. Teramitsu finds it “regrettable,” as Hiroshima is still the only “city of lasting peace” in the world.

In 1989, on the 40th anniversary of the enactment of the law, Mr. Teramitsu gave a talk in Hiroshima and said to the audience: “As long as the law exists, I hope that the citizens of this city of one million people will live with the awareness and the pride that they are residents of a place that is a symbol of lasting peace.”

The late Tsukasa Nitoguri, former chair of the Hiroshima City Council, met privately with Douglas MacArthur to pursue enactment of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law

“I imagine that my father's actions, including his private meeting with Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur, may have made some contribution toward the enactment of the law,” said Akira Nitoguri, 77, the oldest son of Tsukasa Nitoguri, the former chair of the Hiroshima City Council. Akira, a company official residing in Minato Ward, Tokyo, was a university student in Tokyo at the time and he recalls his father visiting there to support Hiroshima's reconstruction efforts.

In February of 1949, Mr. Nitoguri met with Douglas MacArthur, then Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. A year earlier, Mr. Nitoguri had shared his enthusiasm for the “reconstruction of the city of peace” with Brigadier General Crawford Sams of the GHQ, who visited Hiroshima to handle the matter of determining a site for the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC). It was through Mr. Sams' superior that a meeting was arranged between Mr. Nitoguri and Mr. MacArthur. Akira said, “I heard that the commander only said that he thought it was a good idea and my father should work hard to advance the project. But I believe that Mr. MacArthur's approval was one factor that helped move the government to act.”

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law was realized thanks to a combination of Hiroshima's appeal to the GHQ, including the effort made by Mr. Nitoguri, and the actions of Mr. Teramitsu and others. Mr. Nitoguri once took part in a roundtable discussion and shared his feelings in connection with the tireless efforts he made to help reconstruct the city of Hiroshima, saying: “Images of the A-bomb victims fortified my mind in the campaign for reconstruction. Because of the catastrophic scenes seared into my memory, I was able to sustain my energy for the campaign.”

Chimata Fujimoto, aide to Hiroshima mayor, writes objective for proposal

On May 10, 1949, an explanation of the aim of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law was provided at a plenary session of the Lower House. Chimata Fujimoto, 78, a resident of Asaminami Ward who worked for the Hiroshima mayor’s office then and wrote the description of the proposal's objective, looked back on those days and said: “I did my very best.”

At the time, a group of people involved in the city's reconstruction effort were in Tokyo to promote the campaign. They were staying at a Tokyo inn, huddled together in close quarters. For more than a month, Mr. Fujimoto worked on articulating the objective of the law, writing until late at night in the office of an Upper House member, a representative of the Japan Socialist Party from Hiroshima. If he pursued this work at the inn, he felt, he would trouble the others.

In reality, members of the Upper House were more eager to submit the bill for the law than Lower House members. Partly because Lower House members were busy due to the general election, Upper House members obtained prior approval from the GHQ. On May 9, one day before the Lower House side submitted a bill of the same kind to its chamber, Upper House members submitted their own bill with 102 proponents. The Lower House side then quickly gathered 15 proponents and submitted a bill with the same contents the following day. The Lower House skipped committee deliberations and approved the bill that day. On May 11, the Upper House approved the bill which came from the Lower House. The bill proposed by the Upper House was scrapped.

It was a “me first” fight between the Lower House and the Upper House over the enactment of the law, but the objective of the proposal, which had been written by Mr. Fujimoto, was read aloud at the Lower House. “A parliamentarian came to pick up the draft a few days before the plenary session,” he recalled. “It seemed like he had barely looked at it before he stood up in the House to read it.”

(Originally published on February 5, 1995)