History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 4, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

Medical Care in the Early Aftermath of the Bombing I

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

“I will follow that system of regimen which, according to my ability and judgment, I consider for the benefit of my patients.” Hippocrates, the legendary doctor of ancient Greece, made this oath to himself. I don’t believe I’m the only one who is deeply moved, linking this oath, which has been handed down from generation to generation as the finest of medical ethics, to the doctors and nurses who have dedicated themselves to relief efforts in the aftermath of the Great Hanshin Earthquake.

The same thing also occurred in Hiroshima 50 years ago. Despite their own suffering, a large number of doctors stayed true to this oath through the aftermath of the atomic bombing, a calamity confronting human beings for the first time in history, and would later fall ill themselves, sometimes fatally. Even the taboo involving A-bomb-related issues during the period of occupation did not deprive doctors of the passion with which they sought to learn the truth of unknown A-bomb diseases.

The Chugoku Shimbun now looks at the “oath” of the A-bomb doctors, concentrating on the “Tsuzuki Group of the Department of Surgery at the University of Tokyo,” which played a leading role in A-bomb-related medicine early on, and “doctors in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima,” who have strived to treat the aftereffects of the atomic bombing under circumstances that could be called a vacuum of medical care.

Shadow of radiation over white blood cells: Dr. Tsuzuki is first to recognize A-bomb disease

I passed through the Red Gate of the University of Tokyo. The main building of the Faculty of Medicine stands in front of a row of gingko trees. On the third floor of the grand, brick building, I “encountered” Midori Naka, a Japanese stage actress of the Shingeki style, or the Western-style drama that was newly developed in modern Japan.

I opened a heavy iron door and whiffed the sweet smell of medicinal alcohol. Before me was a line of 2,000 specimens. In one corner was a sign that read “Specimens of A-bomb diseases.” Thirty-eight tissue samples that were remarkable in their indication of A-bomb-induced damage were preserved in glass containers. Among them were tissue samples from Ms. Naka’s lung and bone marrow.

Ms. Naka was an actress in the traveling troupe “Sakura-tai,” or “Cherry Blossom Unit.” She was dispatched to the city of Hiroshima in June of 1945 by the Japan Federation of Movement Theater, which was established under wartime regulations. She experienced the atomic bombing in a dormitory in the Horikawa area, about 750 meters from the hypocenter, and died 18 days later.

Ms. Naka’s purple lung tissue was seven centimeters wide and three centimeters long. The center of the tissue was a blackened color. The description read: “Tissue shows an extensive hemorrhage.” This must have been the cause of the pain in her chest, which began after she suffered the atomic bombing and continued until her death. The bone marrow sample was taken from her thighbone and breastbone. It has turned a faint yellow, which is said to be an indication of aplastic anaemia.

Ms. Naka’s specimens were identified as “T・1,” which means she was the first patient with A-bomb disease on whom the University of Tokyo conducted an autopsy. Requesting that autopsy was Professor Masao Tsuzuki. At the time, he was the only expert with the ability to make adequate judgments involving A-bomb diseases. In other words, Ms. Naka was, in a sense, “the starting point for A-bomb-related medicine.” In view of the clinical course of her illness and the autopsy that was performed on her remains, she is officially recognized as having suffered the first case of A-bomb disease in human history.

Ms. Naka was a member of the inaugural class at the Puroto Dramatic Workshop, an institute of left-wing drama that opened at the Tsukiji Little Theater. “She could not help but love drama. She was far from beautiful, but she had a big heart. She was like a big sister to those around her,” recalled Seiji Ikeda, 82, a resident of Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo, who stayed with the Sakura-tai until the end of July 1945.

On the day of the atomic bombing, Ms. Naka was washing the dishes, as it was her turn to cook. The moment she felt the flash, she became trapped under the wreckage of the building. In desperation, she crawled out of the wreckage and then fled to the Kyobashi River. There, she suffered from severe vomiting and pain in her chest. Her clothes were gone by that point; she found herself dressed only in her underwear. Though she was received at a first-aid station in the Ujina area, the aid station was thronged with the injured and she was given no treatment.

The A-bomb survivors she saw from the corners of her eyes, groaning in pain and passing away, made Ms. Naka foresee her own death. Three days after the atomic bombing, when she heard that the first train since the blast would depart Hiroshima, she cloaked her injured body with a tattered futon sheet (some say it was a blanket) and ran toward the city of rubble, where fires still burned here and there.

She had no idea that fellow Sakura-tai members were already dead or were dying at that very moment, among them the splendid actor Sadao Maruyama from the Tsukiji Little Theater; Keiko Sonoi, the former star of the Takarazuka Revue Company; and Kyoko Habara from the city of Fukuyama in Hiroshima Prefecture, who belonged to the Nikkatsu Corporation.

“I’ve made it home, surviving the incident in Hiroshima. I’ll now perform in a play again.” On August 10, Ms. Naka, who managed to reach Tokyo, where her mother had been waiting for her, sent a postcard with this message to her friend. The sentiments of her message were suffused with her joy at having fled the living hell of Hiroshima. Still, the “incident” that she had survived inexorably took hold of Ms. Naka’s body.

On the morning of August 16, the day following the end of the war, Rei Ota, 72, then a junior in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Tokyo and now a doctor and resident of Setagaya Ward, Tokyo, saw Ms. Naka staggering near the medical department’s Tatsuokamon Gate. “I’ve come from Hiroshima,” Ms. Naka told him. Dr. Ota understood immediately. Just the day before, he had attended Professor Tsuzuki’s lecture on atomic bombs.

Dr. Tsuzuki was an expert on radiation and he had studied oncology and radiology at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States. About 20 years before the atomic bombing, he attended an academic meeting in the United States and reported on the results of a test in which he applied X-rays to the body of a rabbit. Dr. Tsuzuki said that his talk was met with a tepid response, with such comments as “It’s highly unlikely that the human body will be exposed to such a massive dose of radiation at one time.”

Peering through a microscope, Ms. Naka’s doctor, Yoshio Shimizu, now 72 and a resident of the town of Kurosaki in Niigata Prefecture, tilted his head. Ms. Naka’s white blood cell count stood at 400, only one-tenth the usual number. With a smile, Dr. Tsuzuki ordered the white blood cell count to be measured again, saying, “It’s not that I’m doubting you.” But no matter how many times Dr. Shimizu measured Ms. Naka’s white blood cells, the results were the same. Upon hearing the report, the color drained from Dr. Tsuzuki’s face. The next day, Ms. Naka’s hair began to fall out.

On August 22, Dr. Tsuzuki, who became convinced that the damage to Ms. Naka’s health had been caused by radiation as he observed the clinical course of her illness, visited the Army Medical College and proposed sending an investigative team to Hiroshima. As Dr. Tsuzuki expected, there was a succession of cases in Hiroshima in which people who had been injured in the bombing were stricken with the same symptoms as Ms. Naka and then died, a development that bewildered and horrified doctors.

Ms. Naka was in such agony that her writhing could not even be contained by the hospital’s whole team of nurses. But on August 24 she had grown oddly calm. When Dr. Shimizu told her that he would go to lunch, she made a smile and said, “Yes, go ahead.” But when he was away, a nurse called to tell him that Ms. Naka had taken a sudden turn for the worse.

Dr. Shimizu, who now operates a private hospital in the suburbs of Niigata City, said in a choked voice: “I can only call to mind Ms. Naka’s smile at the time.” Ms. Naka passed away at the age of 35. One hour later, with unprecedented speed, a pathologic autopsy began. On a list of hospitalized patients, the identification of her condition, “abrasions covering the body,” was crossed out in pencil and altered to read “wounds and lacerations to extremities, and A-bomb disease.” With Ms. Naka the last casualty, all nine members of the Sakura-tai perished as victims of the atomic bombing.

On August 30, Dr. Tsuzuki arrived in Hiroshima, leading an investigative team. “Yesterday I examined a rabbit exposed to radiation, and today I’m forced to do the same thing on human beings.” Dr. Marcel Junod of the International Committee of the Red Cross, who had come to Hiroshima with medical supplies, said that he was shocked to see Dr. Tsuzuki speaking in a pained voice with the brain of an A-bomb victim in his hands. Dr. Tsuzuki, astonished by a catastrophe that was greater than he had expected, spearheaded the start of A-bomb-related medicine, holding a lecture on A-bomb diseases on September 3 for the first time in the world and presenting treatment measures for A-bomb survivors.

In the aftermath of the war, the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) issued a press code and sought to monopolize the research being conducted on the A-bomb damage. The pathological specimens taken from Ms. Naka were, with the exception of certain portions, transferred to the United States. And in 1947, Dr. Tsuzuki was punished for his efforts by being removed from public office on the grounds that he once served as a naval surgeon at the rank of major general.

I visited Hagie Ezu, 84, in a quiet residential area in the city of Kamakura in Kanagawa Prefecture. Ms. Ezu, the author of “Sakuratai Zenmetsu” (“The Annihilation of the Sakura Unit”), took part in the dramatic workshop, alongside Ms. Naka. “I believe that her lasting opposition to war led her to unconsciously turn to the Tsuzuki Group of the Department of Surgery,” Ms. Ezu said. Going to the University of Tokyo Hospital from Ogikubo was unthinkable at the time.”

Ms. Ezu showed me a photo of Ms. Naka playing the part of Geisha Osen at the Tsukiji Little Theater, a role for which Ms. Naka earned positive reviews. Midori Naka was a Shingeki-style actress who left this world without having had the chance to perform a leading part. However, since the day of the atomic bombing, she has continued to play the heroine of a human tragedy.

As August 6 approaches, doctor displays photo with a wish for peace

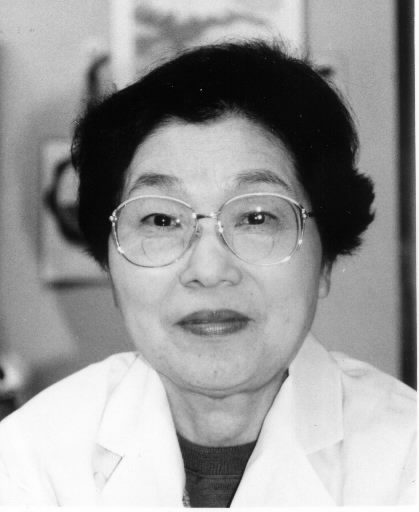

As August 6 approaches, Hagie Ota, 73, a resident of Higashi Ward, Hiroshima, displays a photo in the waiting room of her clinic. In the photo, a young woman, without a white doctor’s coat, is treating a boy. Few people notice that the woman is Dr. Ota.

The photo was taken in October 1945, in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, by Shunkichi Kikuchi, a member of the Japan Film Corporation’s production crew for A-bomb documentary films. The setting was a first-aid station that had been set up at Fukuromachi Elementary School. The photo was returned from the United States in 1968. “The hair band was a piece of colored cloth that had been given to be used as a bandage,” Dr. Ota said. “Please look at the desk. There’s only ointment. I picked up that washbasin in the ruins of the fire.”

Dr. Ota, who had graduated from a women’s medical school earlier than originally planned and was working for the current Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital, experienced the atomic bombing in the garden of her house, which had a clinic and was situated two kilometers from the hypocenter. Her home was completely destroyed. The feeling that she was suffocating, due to falling plaster, roused her back to awareness. Waves of people suffering from burns were surging toward her. Dr. Ota unconsciously joined the crowd, too. Then she thought, “I’m a doctor. I mustn’t flee.”

At a private home, near a shrine, she gave aid to the injured who had flocked there. A military doctor with whom she gave emergency medical treatment died the next morning. From August 10, though suffering herself from headache and nausea, she provided medical treatment at a first-aid station in Furuta. But she could do nothing more than apply Mercurochrome and zinc oxide oil to people’s burns with an ink brush that became stained with pus. Sorrow came over her as it seemed all she could was check the pulse of the survivors and watch them pass away, one after the other.

Ultimately, Dr. Ota was involved in medical relief activities in connection with the bombing for two years. At that time, Hiroshima was not a place to make use of her specialty, ophthalmology. “Since that day, I have been in poor health,” she said. “I even felt regret over joining the relief efforts. But when I saw this photo, I felt as if I had demonstrated my responsibility as a doctor... I now display this photo as an expression of my small wish for peace.”

Occasionally, someone will look at the photo and say: “Doctor, this is you.” At such times, she makes a point of sharing her story.

[Reference] “Warrior without Weapons” by Marcel Junod

(Originally published on February 12, 1995)