History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 5, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

The Early Days of the A-bomb Survivors’ Movement

by Yoshifumi Fukushima, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

There is no catch-phrase on a poster created five years ago by the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations, a nationwide organization of A-bomb survivors, for the 45th anniversary of the atomic bombing. With the heading “Juyonsai no Tsume,” (“Fingernails of a 14-year-old”), the story of a death due to the atomic bombing, written in both Japanese and English, fills up the poster.

The story involves a boy, a middle school student at the time, who suffered severe burns in the blast. He begs his mother for water, but his mother steels her heart and refuses, afraid that the water will harm him, as it seems to have harmed other victims. When the boy rubs his arms, the skin peels away and his fingernails drop off. Unable to bear his thirst, he sucks at the fluid oozing from his fingertips. The next day, this 14-year-old boy dies.

The A-bomb survivors’ movement was originally sparked by a rage that had no outlet, and that movement has been sustained to this day. In the beginning, suffering from poverty and radiation-induced health concerns, the A-bomb survivors called for medical treatment and support for their livelihoods. They did not ask for charity. The movement has championed their opposition to nuclear arms, which deprived them of their health, their livelihoods, even their humanity. At the same time, the movement has involved a struggle in which the survivors have questioned where the responsibility lies for their loss.

The Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations, which organized the A-bomb survivors’ movement, remained unified even in the face of a split in its campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, and continued to point to the nation’s responsibility in calling for enhancements to the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law. Now, though, the organization faces the new problem of an aging membership. The silent cry from the poster with the story of the 14-year-old boy is: “No more hibakusha.” That cry will linger until the day nuclear weapons are eliminated from the earth.

Kiyoshi Kikkawa, “Atomic bomb victim No. 1,” shows keloid scars as warning

Keloid scars were raised on his back, giving the impression of pine cones. In the auditorium of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, a team of American journalists and scientists surrounded this male in-patient, their cameras flashing in surprise.

A voice said: “Kiyoshi Kikkawa, Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1.” It was April 30, 1947, two years after the atomic bombing. Since that moment, Kiyoshi Kikkawa became known as “Genbaku Ichigo,” or “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1.” Whenever visitors came to Hiroshima from other parts of Japan or from overseas, Mr. Kikkawa would show his back at their request, despite sometimes being called a “heiwaya,” or “peacemonger.”

“I remember my husband returning to his hospital room and murmuring that it made him sad,” said Mr. Kikkawa’s wife Ikimi, 73, a resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima. When the hospital first asked him to show his back, he reacted sharply: “I’m in pain because of the atomic bomb, dropped by the United States. Why should I show them my body, too?” But Ikimi said that her husband contained his indignation and humiliation, then went out to face the flashbulbs.

“He was crying inside when he exposed his keloids,” Ikimi said. “I think he did it because he wanted to send a warning so that the suffering of the A-bomb survivors would not be repeated.” A photo of her husband, who passed away nine years ago in January 1986, gazed down at Ikimi from the wall.

Mr. Kikkawa was exposed to the flash of the atomic bomb the moment he entered his home in the Hakushima district. He had just come off the night shift at the Hiroden Streetcar Company, helping to make preparations against aerial attacks. The skin on his back and his elbows, both severely burned, hung from his body in tatters. For more than two months, he and his wife, who also suffered burns, were given treatment at a temple in the Kabe area. While he was there, victims of the bombing were being cremated on a nearby riverbank, day and night. As summer turned to fall, his wife, who had regained some mobility, took to boiling the stalks and leaves of sweet potatoes in an empty can, enabling them to survive.

At the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, where Mr. Kikkawa was hospitalized in February of 1946, straw mats hung over the windows, still blown out from the blast, and snow lay in the hospital rooms that winter. After the couple sold some timber from mountainous land that Ikimi owned, and Mr. Kikkawa began receiving public assistance, he proceeded to undergo 16 operations, including a skin graft operation, during the more than five years he spent in the hospital. When he asked for a different kind of medicine, the hospital brushed him off, telling him, “Expensive medicines aren’t available for welfare recipients.” Even at the hospital, he was dogged by the miseries of poverty.

In the spring of 1951, the couple slept out in the open, with a small trunk for their possessions, in an area crammed with shacks near today’s Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. They had nowhere to go after Mr. Kikkawa was discharged from the hospital after he called for improvements in the hospital’s living environment. Finally, the couple managed to rent a room at an acquaintance’s house and Mr. Kikkawa hunted for a job, but to no avail. A-bomb survivors, who tired easily and often needed to take a day off after exerting themselves, were even chastised as having a “lazy disease.”

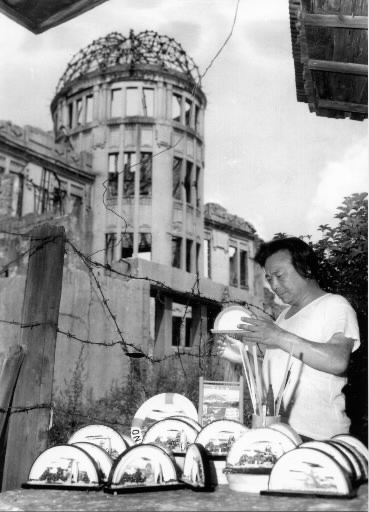

Worn out from his job search, Mr. Kikkawa would often stop by the A-bomb Dome in the evening and look up at the ruined building. A bicycle dealer approached him one night and said, “Why don’t you open a souvenir stand by the dome?” On the first day he opened his stand, Mr. Kikkawa set out two boxes and began to sell picture postcards, among other things, which had been prepared by the bicycle dealer. He brought in 250 yen, equivalent to the daily wage of a day laborer. With this money the couple bought rice and vegetables, and was able to enjoy a hearty meal for the first time since the atomic bombing.

Japan was still under U.S. occupation at the time. The previous year, the City of Hiroshima was unable to hold its annual peace festival as a consequence of U.S. sensitivities when the Korean War broke out. The offensive against communists was growing increasingly severe. Despite the fact that a large number of A-bomb survivors were suffering from radiation sickness and poverty, the occupying forces kept a strict eye on surveys and records which depicted the reality of the atomic bombings. Under such conditions, Mr. Kikkawa began to make visits on foot to other survivors.

“My husband always said, ‘A-bomb survivors are in a vulnerable position. Though the City of Hiroshima is putting its energy into reconstruction, A-bomb survivors are being left behind. If this is the reality of the situation, then two people have more power than one. We have to join hands,’” Ikimi recalled. Mr. Kikkawa did not even take the streetcar. He wore out his shoes visiting the homes of A-bomb survivors and asking about their living conditions.

At the end of August 1951, about 30 A-bomb survivors, Mr. Kikkawa among them, formed the “Rehabilitation Group for A-bomb Survivors.” The group would gather at a small warehouse they rented by the moat surrounding Hiroshima Castle. It was the first organization of its kind for A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima and served as a forum for discussing the problems of daily life and economic independence faced by the A-bomb survivors. They met three times a month, in the evening, and a police officer from the Hiroshima Nishi police station (now, the Hiroshima Chuo Police Station) had them under constant surveillance. “The next morning, we were always asked about what we discussed the previous night,” Mr. Kikkawa said. The owner of the warehouse, who thought they were involved in illegal activities, no longer would allow them to use the building.

The following August, Mr. Kikkawa established the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association, a new organization for survivors, along with poet Sankichi Toge and others, who often visited his souvenir stand. Roughly 50 A-bomb survivors attended the group’s first gathering at Chion Hall. As its agenda, the group decided to pursue such things as assistance for medical treatment, aid to the poor, and peace efforts. Though ill-defined, these aims would serve as the starting point for the pillars of the subsequent A-bomb survivors’ movement, including reimbursement of medical expenses by the central government, free medical checkups, and surveys of the actual conditions of the A-bomb survivors.

The late Ken Kawate, secretary general of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association, and then a student of Hiroshima University, wrote about the function of the group in his memoir: “The association was more of a call to create an organization for A-bomb survivors. But its establishment was also part of the struggle of the survivors, who continued to suffer with no formal organization and no one to turn to for help, to stand up in solidarity.”

In April 1952, the peace treaty between Japan and the United States went into force. The post-war occupation of the past seven years was over and moves to probe the reality of the atomic bombings began in earnest.

The efforts by Mr. Kikkawa and others eventually prompted the establishment of other organizations of A-bomb survivors. Various groups of A-bomb survivors they came together, which led to the formation of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations in May 1956 and the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers in August of the same year. Three months after the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organization was established, the Hiroshima Prefectural Conference of A-bomb Sufferers, which was held in the city of Hiroshima, issued a declaration: “Now, having gained the confidence to go on with our lives, we will lead the efforts of the A-bomb survivors with courage and determination.” This was in the 11th summer following the atomic bombing.

Mr. Kikkawa, however, stood outside the nucleus of the new, growing organizations of A-bomb survivors. After a stroke led to a struggle of over eight years with poor health, he died nine years ago at the age of 74. He had spent 12 years of his life denouncing the atomic bombing and revealing his keloid scars to tourists and students visiting Hiroshima on school trips, among others, beside the A-bomb Dome. He was even accused of “capitalizing on the atomic bombing.” Recalling her husband, Ikimi said: “He often wished his body could be restored to the way it had been before the blast. I guess the defiant way he lived, sticking to his own guns, were misunderstood in a way. But his arguments were always cries from the bottom of his heart.”

Mr. Kikkawa once told his wife, “I’ll be involved in the peace movement for the rest of my life. Prepare yourself for that.” However, four months before he passed away, he said to her: “You’ve done your best. From this point on, live a more easy life.” The couple had no children. After her husband’s death, Ikimi began to speak out about her A-bomb experience. She shares her story at the former site of their souvenir stand, in the shadow of the A-bomb Dome. This is the spot where the couple’s tears once flowed.

Tokyo District Court proclaims illegality of atomic bombings in lawsuit ruling

“The atomic bombings were a violation of international law.” The ruling by the Tokyo District Court on December 7, 1963, in connection with a lawsuit filed over the atomic bombings, was a landmark decision that provided significant support for the A-bomb survivors’ movement, which had been seeking a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs, as well as relief measures for damage caused by the blasts.

The suit was brought by five A-bomb survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, seeking redress from the central government for A-bomb damage. However, the higher aim of the late Shoichi Okamoto, the first attorney for the plaintiffs and a member of the Osaka Bar Association, was to argue the illegality of the atomic bombings.

At the Tokyo Tribunal of War Criminals, where judgments were passed on Japanese military figures, Mr. Okamoto had presented a brief for Akira Muto, the former major general at the Military Affairs Bureau of the Army Ministry. With the Allied Powers showing no signs of regret over the atomic bombings, Mr. Okamoto made up his mind to file the lawsuit.

“Mr. Okamoto visited A-bomb survivors, who were mired in poverty and suffering from prejudice, and persuaded them to join the lawsuit,” recalled Yasuhiro Matsui, 62, a lawyer from the city of Mihara in Hiroshima Prefecture who succeeded Mr. Okamoto as the plaintiffs’ attorney. Mr. Okamoto died suddenly of illness at the age of 67, three years after the lawsuit was filed.

In the court ruling, which was made eight years after the suit was filed, presiding judge Toshimasa Koseki dismissed the plaintiffs’ claim for compensation, saying, “Individuals have no right to claim compensation for damage in respect to both domestic and international law.” However, he emphatically condemned the atomic bombings, stating, “The atomic bombings were indiscriminate attacks against open cities and illegal acts of combat from the standpoint of international law. The central government, which instigated the war with its own authority and responsibility, should provide sufficient relief measures to address the consequences of this war.” He concluded: “The more I consider this case, the more I cannot help but deplore the poor politics.”

Mr. Koseki, 81, who now practices law in Tokyo after retiring from the bench, commented: “I still hold the same view as I did when I made the ruling.” Mr. Matsui, the plantiffs’ attorney, stressed, “This has been the only court ruling made with regard to the atomic bombings. That decision was also seen as the grounds for the campaign for the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, which is based on the spirit of state compensation.”

(Originally published on February 19, 1995)