History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 7, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

Second-generation A-bomb survivors

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

This article will start with a personal experience of the writer: Several years ago, my son developed a high fever and purple spots broke out on his abdomen. The doctor’s suspicion was leukemia. As my wife and I are both second-generation A-bomb survivors, the words “atomic bomb” flashed through my mind. A few days later, a blood test confirmed that leukemia was not the culprit after all. But the cause of the purple spots has remained a mystery.

“To this point, genetic effects involving exposure to radiation have not been observed.” So goes the general thinking of the medical community. However, when a health concern arises, A-bomb survivors and their descendants suspect a link between the atomic bombing and their condition. The bottomless horror of the bombing has been seared too deeply in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima to scoff at this mindset as merely a sentimental argument.

The Chugoku Shimbun will peer into the shadows of radiation fears that have fallen on the hearts of A-bomb survivors and their kin, turning our attention to a boy, a second-generation A-bomb survivor who died of leukemia, and doctors involved in the treatment of A-bomb survivors at the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital.

Story of 7-year-old boy raises question of “genetic effects”

Facing the gravestone, the father spoke these words in his head: “An atomic bomb took your life and your mother’s life. I’ll do everything in my power to rid the world of these weapons.”

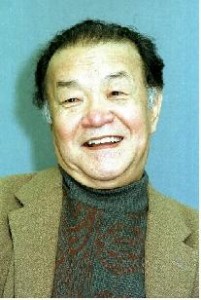

The father, Kenzo Nagoya, 65, was standing in the cemetery on Mt. Futaba, which commands a sweeping view of the city of Hiroshima. Mr. Nagoya, the executive director of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations and a resident of Nishi Ward, quietly put his hands together in prayer. The gravestone was inscribed: “Fumiki: Seven Years Old.” That day, February 22, was the anniversary of his son’s death. Fumiki, his second son, passed away 27 years ago.

Fumiki was a second-generation A-bomb survivor. The boy’s courageous battle with leukemia, which he fought fiercely for two years and eight months, stirred anew the question of genetic effects linked to the atomic bombing. “It was cold and it snowed heavily that day,” Mr. Nagoya recalled. “Not like today.” He squinted as if searching for the image of his young son.

Fumiki loved to play ninja and draw pictures of spaceships. It was the evening of a hot, summer day, just prior to his fifth birthday, when the shadow of death crept over this ordinary boy. He developed a fever of nearly 40 degrees Celsius. His gums became swollen and he complained of pain in his joints. His mother, Misao, who was gazing hard at the small child as he cried bitterly through the night, reluctantly expressed her fear: “I’m afraid he may have leukemia.”

The memory of that day when she was chased by the flames of the atomic bombing had flashed in Misao’s mind. She was exposed to the bomb while at home in the Ushita area, 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. She lost her younger sister to the blast and since that time suffered poor health herself. Leukemia was a notorious A-bomb disease and every A-bomb survivor, in the back of their mind, harbored fear of falling victim to this illness.

The couple waited for dawn to break, then rushed to the Hiroshima University Hospital. Their ominous feeling turned out to be right: Fumiki was diagnosed with acute leukemia. Misao buried her face in the bed where her son lay fast asleep. Kenzo, in shock, stood rooted to the spot alongside them.

Yuko Yamaguchi, 78, a resident of Shinagawa Ward, Tokyo and an author of children’s books, was standing along a street in Hiroshima, engaged in a fundraising campaign for A-bomb survivors when the news was whispered to her: Mr. Nagoya’s boy has come down with leukemia. The news shocked her. “When the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) was established in Hiroshima, the first to arrive was a geneticist,” Ms. Yamaguchi said. “Fumiki made us realize the importance of that fact.”

With Dr. James Neel and others leading the work of the ABCC, from the time the organization opened in 1947 it was involved in investigating the possible genetic effects from the radiation released by the atomic bomb. However, ABCC repeatedly discounted this possibility on the grounds that they had obtained no data to confirm such effects.

In response, Ms. Yamaguchi took action. Along with Kiyoshi Sakuma, a professor at Hiroshima University, Munetoshi Fukagawa, a poet, and others, she promptly sought to form a group that would protect prenatally-exposed survivors and second-generation survivors. But they ran up against a wall: the unfamiliar words “second-generation A-bomb survivors.” One after another, voices were raised making such arguments as “This will stir discrimination against A-bomb survivors” and “It will leave children feeling insecure; we should let them live in peace.”

But Ms. Yamaguchi would not give an inch. “This problem is not Fumiki’s alone,” she said. “Leaving them as they are is as good as turning our backs on this issue.” In July 1966, one year after Fumiki developed leukemia, the group was established.

Fumiki’s struggle against the disease continued. He tried his best to endure the bone marrow examination, which brought him terrible pain, saying, “I hate getting shots.” Koichi Kawamoto, 68, Fumiki’s doctor and now a practitioner in Nishi Ward, said, “A new medicine was working and Fumiki’s cancer was in remission. If only the cancer hadn’t returned, there would have been hope of him living a long life...”

A year and nine months had passed since Fumiki’s bout with leukemia began. If three more months had gone by without change, hope was warranted. However, Fumiki’s condition took a turn for the worse again after attending an entrance ceremony for elementary school. He was feeling so weak that he let his older brother carry his cherished school bag. Dr. Kawamoto recalled: “I had a bad feeling. He had always hated getting shots, but he put up with it quietly that day.” In April Fumiki received his regular checkup. Mr. Nagoya, who was waiting for a call at his workplace with the results, realized everything from his wife’s weeping voice over the telephone: Fumiki’s leukemia was back.

Death drew closer inexorably. Still, Fumiki demonstrated a remarkable energy for life. He regained his strength, to some degree, and could even pay visits to a swimming pool. He was trying hard to swim one meter farther than he had before. One day, he murmured: “I want to live a little longer.” Had such a small child realized his own fate? Mr. Nagoya could only manage a smile in reply.

Six months later, Fumiki died. At the time, a stick of gauze held in his mouth was about to fall out. His father urged him to bite down on it. Fumiki gulped a breath to do as his father said. It would be his last breath. At 2:45 a.m., Fumiki Nagoya’s battle with leukemia had come to an end. Mr. Nagoya wept, caressing Fumiki’s cheeks, still warm.

Fumiki’s death ignited concerns over second-generation A-bomb survivors. The following year, two more second-generation A-bomb survivors, Takako Okuno, 17, and Akio Morii, 5, died of leukemia as well. A-bomb survivors’ organizations, including the Hiroshima Prefecture A-bombed Teachers Association and the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, as well as labor unions, including the Hiroshima Teachers’ Union, the National Railway Workers’ Union, and the current All NTT Workers Union of Japan, called on government officials to investigate the actual conditions of second-generation A-bomb survivors and pursue thorough measures to care for the health of second-generation A-bomb survivors. The Hibakusha Youth League was also established with second-generation A-bomb survivors in leadership roles, and the group undertook active efforts.

Two years after Fumiki died, Mr. Nagoya was invited to Ryojo Junior High School in the city of Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture. The school was putting on a play based on the memoir of their son’s struggle to survive his illness, entitled “Boku Ikitakatta,” or “I Wanted to Live,” which was written by Mr. and Mrs. Nagoya. Students from the school were involved in the performance. The couple heard sobs in the audience and were deeply moved.

“Fumiki lives in the hearts of these children,” Mr. Nagoya thought at the time.

Yoshitaka Fujioka, 61, a Kure resident, was the teacher who served as the director of the play. His voice broke with emotion as he recalled: “The students were all crying in the dressing room. Through performing in the play, they must have been struck by the horror of the atomic bombing.” In January of this year, Mr. Fujioka received a phone call from one of his former students at the time. She is now a member of a drama group that performs for children and she said she wanted to perform the play “Boku Ikitakatta” with her group. Another of his former students has become a teacher and leads peace education classes. The experience of the play as junior high school students, and the emotions awakened on that occasion, served as a turning point in their lives.

On the gravestone on Mt. Futaba, inscribed next to Fumiki’s name is the name of his mother, Misao. She died of liver failure in 1986 at the age of 56. “My wife developed the same purple spots as Fumiki,” Mr. Nagoya said. “I know the medical world dismisses the idea that A-bomb diseases can be inherited, but when I think of the purple spots they both had...” Mr. Nagoya did not experience the atomic bombing himself. But after retiring as a high school teacher, he joined an A-bomb survivors’ organization and has continued his fight against atomic bombs on behalf of Misao and Fumiki.

It is said that no positive proof of the genetic effects of A-bomb radiation has been found. By the same token, to this point it has not been possible to prove that no genetic effects exist. The answer to the question posed by the death of Fumiki Nagoya still awaits, 27 years later.

On the day after Fumiki’s death, Mr. Nagoya wrote in his diary: “Until yesterday, Fumiki was still very much alive. And he was still the child Misao and I brought into this world. But now, he is a child of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, everyone’s child.”

“Yumechiyo” lives on in TV drama

In the 1980s, a three-part television series called “Yumechiyo Nikki,” or “Yumechiyo’s Diary,” was aired by Japan’s national broadcaster NHK. The TV drama, with a story highlighting the aftereffects of the atomic bombing, was met with a strong response by viewers. Played by the actress Sayuri Yoshinaga, the main character was a fictional A-bomb survivor who had been exposed to the atomic bombing while in her mother’s womb. However, she was identified as a second-generation A-bomb survivor on the grounds that her mother was an A-bomb survivor. The broadcaster received a large number of appeals from A-bomb survivors, asking that the character not die in the drama “because this would make my child uneasy.”

The script was written by Akira Hayasaka, now 65. The main character, who ran a house for geisha located in a small town with hot springs in the northern part of the Chugoku region along the Sea of Japan, was struck with leukemia and told that she had only six months to live. The story showed her valiant efforts to live, while weaving in a variety of subplots involving human dramas.

About two weeks after the atomic bombing, Mr. Hayasaka arrived at Hiroshima Station one evening. He was 16 years old at the time, en route to Ehime Prefecture after being discharged from the naval academy. “Large numbers of blue lights, from the phosphorous emitted by the decomposing dead, were floating above the ruins of the city,” Mr. Hayasaka recalled. “I was staring at the scene, thinking that such a sight will probably appear when humans go extinct. I then heard a baby crying in the distance.”

The “symbol of life and death” that he experienced that night has gripped his heart ever since. Then the opportunity arose to create a new drama at NHK and he met Ms. Yoshinaga. “I was in talks with her about the role, thinking she would look lovely dressed as a geisha, and meanwhile I became aware of the fact that she was born in the same year that the atomic bomb was dropped,” Mr. Hayasaka explained. That baby’s cry led to the story of Yumechiyo.

When he was writing the script, Mr. Hayasaka listened to the accounts of A-bomb survivors. “When they told me that they didn’t want me writing the script in such a way that viewers would think that all children of A-bomb survivors have physical disorders, I realized anew how wicked the atomic bombing was,” he said. When the drama was broadcast on TV, the reaction was powerful.

Out of deep consideration for the feelings of the A-bomb survivors, Mr. Hayasaka and his colleagues did not have Yumechiyo die in the TV drama. However, when a movie version of the drama was made, Ms. Yoshinaga expressed her wish that the character die in the film. Thus, the story of Yumechiyo ended with the movie version, an unprecedented development for a drama.

(Originally published on March 5, 1995)