History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 10, Article 2)

Aug. 1, 2012

Korean A-bomb survivors suffer lack of support

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

“As the only nation in history to suffer an atomic bombing, Japan will...” The Japanese government and media, as well as A-bomb survivors themselves, all use this sort of language, making it seem as if the only victims of the atomic bombings are found in Japan. With wording such as this, a whole swath of people are ignored: the victims who reside overseas, including Korean A-bomb survivors.

Immigration to Japan from the southern half of the Korean peninsula has a long history, stretching back to 1910. When Japan colonized that nation, many Korean men came to Hiroshima in search of a livelihood, and eventually brought their wives and children to settle in Japan as well. During the war, there were also conscripted laborers, soldiers, and military employees from Korea. While in Hiroshima, they encountered the atomic bomb.

What lives are the Korean A-bomb survivors, who returned to their homeland with only their broken bodies, leading today? How do they see Japan, which has left them to fend for themselves by not extending medical support beyond its borders? The Chugoku Shimbun explored the reality of the “other Hiroshima” in Hapcheon County, located in the Gyeongsangnam-do District of South Korea.

Japanese government draws distinctions between A-bomb survivors

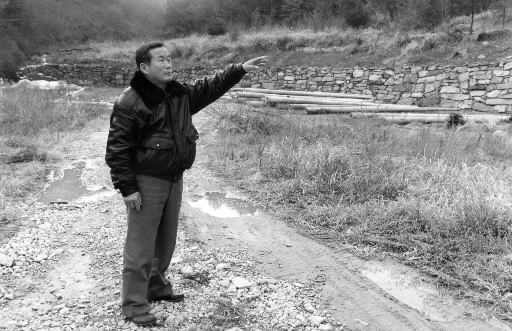

We traveled five kilometers to the east, and over a river, from Hapcheon County’s health care center and clinic. An Yeongcheon, 68, head of the Hapcheon chapter of the Korean Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Association, stopped his bicycle at a clearing about 500 meters from a national road that stretches into the mountains. “This is where it will be built,” Mr. An said.

Mr. An was referring to a welfare facility for A-bomb survivors, which will begin to rise next month as Korea’s first nursing home for survivors of the bombings in Japan.

After construction is complete, the building will comprise three floors and a basement, with a floor space of 2,640 square meters. The first floor will consist of a medical office and cafeteria, and the other floors will have twin, 4-person, and 6-person rooms, as well as an entertainment room. The facility, which can accommodate 80 people, is designed to serve as a center for the medical needs and daily caregiving of Korean A-bomb survivors.

“The plan is for elderly A-bomb survivors who don’t have family to enter the home. However, we don’t have a doctor with expertise in this field, and we don’t know how long the funds to run the home will last...” Mr. An looked unhappy, despite the fact construction would soon start.

The money to build the facility, which amounts to some 2.4 billion won (about 300 million yen), is coming from the Korean Atomic Bomb Survivors Support Fund, which holds a total of 4 billion yen, a donation from the Japanese government for “humanitarian reasons.” However, the way in which these funds would be used was determined in negotiations between the two governments, not in line with the wishes of A-bomb survivors.

The governments have decided to: 1) construct welfare facilities at seven sites around the country, including in Hapcheon and Seoul; 2) hold regular health checkups for A-bomb survivors; and 3) provide financial assistance to pay medical fees.

As a consequence of these allocations, the number of facilities to be established means there will be less money directed to financial assistance for medical care.

Because the construction costs of these facilities will eat up most of the available funds, the monthly distribution of financial assistance for medical care, about 12,000 yen, will also come to a halt. The anger and suspicion felt by the A-bomb survivors, as they fall through the cracks of Korea’s economic growth, are directed at the Korean Red Cross, which has been supervising the fund.

“If I could, I would be happy to leave the money in the government’s hands and have nothing more to do with it.” At the office for A-bomb survivors’ welfare, established two years ago at the Korea Red Cross in Seoul, Oh Cheongeun, 54, the head of the section, heaved a sigh at the predicament of being caught between the governments of Japan and Korea and the A-bomb survivors.

The Red Cross uses the funds to reimburse 20 percent of the medical costs whenever one of the 2,300 registered A-bomb survivors receives treatment at a medical facility. The funds are also used to distribute the “medical support allowance” that serves as financial assistance for the survivors’ social and medical needs. Mr. Oh and his staff of four manage these programs.

At the same time, medical costs cannot be reimbursed when the treatment involves the use of high-tech equipment, like computers, and when certain types of medications are prescribed. The survivors must meet these fees on their own, using the “medical support allowance,” which has led to calls for a larger allowance and a new allowance system.

Mr. Oh sighed again and said, “If we could, we would provide a larger allowance, but there just isn’t enough money. Even so, we still have to build the welfare facilities and maintain them...”

Today, 2.8 billion yen remains from the initial amount of 4 billion yen. Operational expenses this year totaled some 750 million yen, due to additional construction costs involving the welfare facilities. Even if the facility in Hapcheon were the only one to be built and maintained, with medical costs and allowances continuing to deplete the fund at the same rate, the money will be exhausted by the year 2001.

The worries of the A-bomb survivors are not idle ones. “Why does the Japanese government make distinctions between the same survivors?” Jeong Sangseok, 65, chairman of the Korean Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Association, quietly wonders from the Seoul office. Mr. Jeong is also from Hapcheon County and he experienced the atomic bombing in his youth after moving to Hiroshima with his family. His mother, who was mobilized to work in the Tokaichi area to help create fire lanes in the event of air raids, died at the site.

Mr. Jeong, who was elected chairman in February, expressed bitterness toward Japan as he said, “Even when we ask for compensation, the Japanese government only offers us meaningless apologies. Nobody really listens to us.” He also feels frustration over the fact that, as head of the organization, he must respond realistically to the demands of his membership over the issue of how the remaining funds should be used.

“It’s not like we want better treatment than the survivors in Japan,” he said. “We just want reasonable support. We want Hiroshima, a place that holds many memories for us, to extend its cooperation so we can look back and think: ‘It was hard, but I’m glad I was able to live as long as I have.’”

Are the wishes held by the city of Hiroshima, as it appeals for peace inside and outside Japan, sufficient to safeguard the lives of people regardless of nationality or culture? An answer to this question awaits.

Life today for Son Jin Doo, who won his lawsuit involving the A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate

A case that came before Japan’s Supreme Court in 1978, which involved a lawsuit over the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, played a large part in fueling momentum for the support of all A-bomb survivors, both those inside and outside Japan. The case has come to be known as the “Son Jin Doo Case.”

Son Jin Doo, 68, experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, then later stole passage to Japan from Pusan in 1970 in order to receive treatment for an A-bomb-related illness. He requested the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate from Fukuoka Prefecture, but his application was rejected by the Ministry of Welfare when it determined that Mr. Son was not entitled to the rights of a resident. In his lawsuit demanding that this decision be overturned, Mr. Son won both his first and second hearings.

Finally, the Supreme Court weighed in and backed Mr. Son’s claim by stating that the law granting medical treatment for survivors of the atomic bombings is a law which involves humanitarian relief measures, and, as such, should also apply to those from overseas who have gained entry to Japan.

The appeal of a single Korean A-bomb survivor was able to shift the stance of the government, which, until that time, had refused to provide Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificates to survivors residing outside the country. The case paved the way for the passage of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.

Seventeen years have passed since Mr. Son’s victory at the Supreme Court. The man who made his mark in the history of “A-bomb lawsuits,” lives quietly, by himself, in the city of Fukuoka. He has little contact with his former supporters now.

“I caused trouble for everyone, doing all those stupid things...” He mutters about his life following the legal victory, speaking in the dialect of his birthplace, Osaka. The “stupid things” he refers to involve criminal incidents, such as theft, that appeared in the newspaper on several occasions. In the wake of these incidents, many of his supporters severed ties with him.

“Gambling was always the reason,” he explained. He talked about that time without reservation, but he had a vacant look as he spoke. In one corner of the messy room are his Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and Special Residence Permit, both safely preserved. “Everyone who came to Japan and experienced the atomic bombing probably suffered a lot, but they just don’t talk about it,” he said.

He resorted to such desperate measures as sneaking into Japan in order to obtain the survivor’s certificate, which any survivor should have the right to hold, he said. During the six long years his case wound through the court system, he lived in fear of being deported as a consequence of violating the Immigration Control Act. He spent much of his 40s, the prime of his life, at the Omura Dentention House, which was often used as a “way station” for Korean violators of the Immigration Control Act before being sent back to Korea.

The atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima changed the fate of this man and shaped the rest of his life. The weight of his experience is evident in the choices he has made since the bombing.

90% of Korean survivors suffered the bombing in Hiroshima

How many Koreans experienced one of the atomic bombings? There are various estimates, but the exact number of Korean A-bomb victims and survivors remains unknown. Documents from the Home Ministry’s Police Bureau show the number of Korean residents in Hiroshima prior to the bombing. In 1944, there were 81,863 Koreans in Hiroshima (of these, 5,944 were brought to Japan as forced immigrants, including those sent as forced laborers), and 59,573 were living in Nagasaki (20,474 of these were forced immigrants).

How many Koreans, though, were in Hiroshima and Nagasaki when the bomb was dropped, and how many entered the cities in the aftermath? While “Hiroshima and Nagasaki” (Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 1979), a volume edited by both A-bombed cities, states that “determining actual numbers is very difficult,” the book goes on to say that the number of Korean A-bomb victims and survivors is estimated to be 25,000~28,000 in Hiroshima and 11,500~12,000 in Nagasaki.

One basis for this claim is a report on the A-bomb damage issued by the present-day Korean Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Association. This organization offered its own estimate, speculating that, when the bombs were dropped, 50,000 Koreans were in Hiroshima and 20,000 were in Nagasaki and that a total of 40,000 lives were lost. Excluding those who remained in Japan afterwards, 23,000 returned to South Korea. But again, this was only conjecture.

The first full-scale investigation of the matter was undertaken by the Korean Ministry of Social Health in the fall of 1990. In the spring of that year, following the agreement made at a bilateral meeting between the heads of Japan and Korea in which Japan would donate 4 billion yen as financial assistance for the medical care of Korean A-bomb survivors, the Korean government used announcements in the newspaper and on radio which asked survivors to step forward.

As a result, 570 people were newly recognized as A-bomb survivors, and along with those who were already registered with the association of survivors, the total number came to 2,307. Of this number, 91% experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and 88% were suffering from aftereffects of the blast.

Kwak Kwi Hoon, 70, a Seoul resident and a founder and former chairman of the Korean Atomic Bomb Survivors’ Association, points out the possibility that the effects of the atomic bomb can be inherited by offspring. “There is strong discrimination against A-bomb survivors,” he said, “so when we consider our children and their search for a marriage partner and employment, it makes it difficult to openly acknowledge being an A-bomb survivor.”

The number of people who hold the Atomic Bomb Sufferer Register Certificate, which is issued by the Korean Red Cross following an assessment of the applicant, reached a total of 2,348 as of the end of last year. Although this conforms to the number of recognized A-bomb survivors, a wide gap still remains between this figure and the 23,000 people thought to have returned to Korea after the bombings.

In 1989, the existence of 10 A-bomb survivors in North Korea was confirmed for the first time. In the movement to return to the homeland that took place around 1960, it is estimated that 2,055 people from Hiroshima returned to North Korea. Of these people, however, the number of A-bomb survivors is unknown.

(Originally published on March 26,1995)