History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 13, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

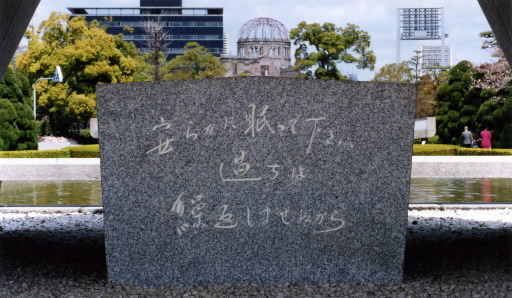

The Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims

by Yoshifumi Fukushima, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

The Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, located in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, not far from the hypocenter, contains a register which holds the names of about 187,000 victims of the atomic bomb. Nearby the Cenotaph is the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, a monument to the victims who remain unidentified. The remains of another 70,000 people rest here. All are A-bomb victims whose lives were stolen away by the catastrophe. Consequently, this part of the city is thought of as a holy site, a repository of souls.

The inscription on the cenotaph, which has weathered two controversies over the appropriateness of its words, is a prayer for the dead and an appeal for nuclear abolition. Even now, 50 years after the end of the war, debate continues between Japan and the United States with regard to responsibility for the bombing. However, in an atomic age in which “nuclear-affected sufferers” are constantly created, an inscription constituting a “vow of mankind” holds a heavy significance. To the remains of those within the memorial mound, still seeking a proper resting place, the passage of 50 years since the dropping of the atomic bomb is no turning point.

The survivors pray for the victims to rest in peace and vow to prevent such a tragedy from occurring again. In this lies the consciousness which grasps the holy nature of the park.

Inscription on cenotaph overcomes controversy

A dark green scrapbook holds yellowing newspaper articles from November 3, 1948. These articles bear headlines with the verdicts of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, trials involving war crimes committed by Japanese military officials that were held following the conclusion of the war. A headline with the words “Tojo and Six Others to be Executed by Hanging” catches the eye. This scrapbook belonged to the late Tadayoshi Saika, formerly a professor at Hiroshima University.

Four years later came the first controversy over the inscription on the cenotaph. Professor Saika’s second son, Hiryou, 67, a former judge and now a resident of Minami Ward, reflected on that time, and the irony of history. “My father probably never dreamed that the Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal, who was a member of the international tribunal and an advocate for the innocence of all the war’s victims, would criticize the inscription that he wrote.”

The English translation, which imbues Hiroshima’s “prayers and promise” in its fifteen words, reads: “Let all the souls here rest in peace; for we shall not repeat the evil.” The original Japanese inscription is carved horizontally in three lines on the stone chest which holds the register of victims’ names. The chest sits within the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, shaped like a clay figure of an ancient type of Japanese dwelling and standing in the heart of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. The cenotaph was completed in the summer marking seven years since the bombing and four years after the international tribunal.

In late July 1952, just before the completion of the cenotaph, Chimata Fujimoto, now 78 and a resident of Asaminami Ward, paid a visit to Professor Saika. Mr. Fujimoto managed the mayor’s office at the time and he came to ask the well-known English professor to compose the inscription. Professor Saika, a bald, easygoing man with a bony face and the nickname of “Hermit,” was temporarily living in the archery training hall of the former Hiroshima High School in Minami Ward.

After consulting some poetry in English, the professor murmured, “Perhaps something like ‘Rest in peace for we shall not repeat the evil.’” Mr. Fujimoto jotted this idea down. Professor Saika then polished the wording and that draft, completed the next day, became the inscription for the cenotaph.

Until Professor Saika entered the scene, Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai had been struggling to devise a suitable inscription. “The Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims needed to be a symbol of Hiroshima and its prayers for eternal peace,” Mr. Hamai recalled. “I had difficulty tying our prayers for the repose of the victims’ souls to a vow.”

Then Mr. Fujimoto introduced Professor Saika to the mayor. The professor was Mr. Fujimoto’s old teacher at the former Hiroshima High School. He was a remarkable man who would hold out an inkstone case and a guestbook to students visiting his home so they could write down their names. He eagerly read difficult English texts, translating them with a smile of satisfaction. Known for his eccentricity, he named his sons “Aporo” and “Hiryou” after the gods Apollo and Sirius of Greek mythology. The inscription was born from his keen knowledge of literature, particularly English poetry.

This all happened at a time when the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, and their nuclear arms race, was intensifying in connection to the Korean War.

Then, in November 1952, three months after the cenotaph was unveiled, Radhabinod Pal paid a visit to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. He had come to the city for the World Federalist conference in Asia. When he heard the English translation of the inscription on the cenotaph, he bristled with anger.

Mr. Pal bitterly criticized the English version of the inscription and its subject “we.” (The Japanese inscription contains no clear subject.) “‘For we shall not repeat the evil’ implies that the Japanese were responsible for this evil,” Mr. Pal said. “Clearly, the Japanese were not the ones who dropped the atomic bomb. The hands of those who actually dropped the bomb have not been purified.” Mr. Pal contended that it was the United States who should make a vow never to again wage war. In the wake of Mr. Pal’s comments, many survivors who had been unable to express their bitterness toward the bomb amid the shock of losing the war sympathized with his words.

Professor Saika protested this reaction. Yoshio Torigoe, 84, his successor at Hiroshima University, typed up his statement of rebuttal in English. “Professor Saika told me he needed to convey his thoughts. It was testimony to the strong belief he felt in his inscription.”

The statement indicated that the inscription expressed the feelings of the people of the A-bomb city of Hiroshima, feelings applicable to the past, present, and future of all of humanity, and that Professor Saika did not wish to hold the narrow-minded view of pointing fingers at the United States when facing the souls of the A-bomb victims. Added at the end of the statement was a line of poetry that suggested the doors to peace could open if we would pray with a sincere heart.

Mr. Pal’s argument stemmed from a feeling of “Asian ethnic nationalism.” In his criticism of the cenotaph, he also said: “If ‘evil’ refers to the previous war, then that, too, is not Japan’s responsibility. The seeds of war were clearly sown by the Western nations to subdue the East.” In this belief lies his rationale for judging the Japanese defendants innocent of war crimes at the international tribunal.

Professor Saika, though, felt just as strongly about avoiding another A-bomb tragedy. In a commentary about the inscription that appeared in a municipal public relations paper, the professor wrote: “The greatest evil committed in the twentieth century was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.”

All four members of Professor Saika’s family are A-bomb survivors. The professor, his wife, and his elder son, who had returned from Kyoto University for the summer break, were at home in Minami Ward when the bomb exploded. His younger son was working in a field at the former Hiroshima High School. The blast knocked the house over, the walls and windows disintegrating. Fortunately, the family was unharmed, but they lost many friends and colleagues. Although Professor Saika was reluctant to speak about his experiences of the bombing, every day he would write down the names of the victims he knew and chant a sutra to remember them. Two years before the end of the war, he was also forced to see off the first 18 students of Hiroshima High School who had been drafted to fight. This was the start of his hatred for war.

On February 1970, 18 years after the dispute with Mr. Pal, controversy over the inscription flared again. The Hiroshima-based “Committee to Correct the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims” demanded that the city change the inscription, saying that it “erases responsibility for an act that can only be considered the height of cruelty.” But the “Committee Against A- and H-bombs” made a counterargument, and six months later, the mayor at the time, Setsuo Yamada, made the decision not to alter the inscription. His reasoning went: “The subject of the inscription is ‘all mankind,’ and the message serves as a warning and lesson to all of us.”

Professor Saika and Mr. Pal were not present at this second round of controversy. The professor passed away in 1961 at the age of 67, and Mr. Pal died six years later at the age of 81. At the very least, these two men shared the same desire that “another Hiroshima” would never again occur in the world.

Half a century has passed since the atomic bomb was dropped. A planned exhibition of A-bomb artifacts at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. was canceled as a result of vehement opposition from the American Legion. They argued: “The exhibition talks about the bombing, but it doesn’t say whose fault it was in the first place.” The city of Hiroshima continues to appeal for the “tragedy of the atomic bombing never to be repeated,” but even after 50 years, the nation that dropped the bomb struggles to understand this “tragedy.” It may be that the controversy over the inscription, even while changing form, continues to rage.

However, Professor Saika’s eldest son, Aporo, now 70, a professor emeritus at Kyoto University and a resident of Kyoto, expresses concern over the Smithsonian incident. “If we continue to feel bitterness toward one another, there will be no end to our struggles, and the spirits of the victims will never be able to rest in peace,” he said. “Thinking about it now, I believe the inscription which calls for an end to conflict among all of humanity was the right choice.” Aporo spoke quietly, in a voice reminiscent of his father.

The statement of rebuttal sent by Professor Saika to Mr. Pal includes the English translation of the inscription. The translation was made with the assistance of an acquaintance at the University of Illinois. The Japanese version of the inscription has no subject, but in English, “we” becomes the subject for “shall not repeat the evil.”

Mr. Fujimoto, who is familiar with this translation, commented: “Those vowing never again to wage war are all the ‘global citizens’ who stand in front of the cenotaph. Whether or not the inscription includes a subject is not the main point of the message.”

The elder son, Aporo, visits the cenotaph whenever he returns to Hiroshima. The younger son, Hiryou, also pays his respects in front of his father’s inscription each year on August 6. “When I think about the victims of the atomic bomb, I’m reminded that we, the survivors, must always keep the pledge of the inscription alive in our hearts,” he said with a somber expression.

At his retirement, five years after the inscription debate raged, Professor Saika wrote the following words in the Hiroshima University Newspaper: “To the whole world, to all of mankind, look toward Japan and follow suit. The inscription is a command to all of us. Are you unable to interpret such a clear command? This shows a lack of wisdom.” These words reflect the aloof nature of the professor.

Article in the Chugoku Shimbun on November 7, 1952

Inscription debate raises mutual resolve to prevent repetition of tragedy

The debate sparked by the argument from Justice Radhabinod Pal has created a stir among intellectuals of every sector of society. There seem to be as many different interpretations of the inscription as there are people. Though these reactions may be different, one idea that is shared by all is the conviction that “the A-bomb tragedy must never be repeated.”

Isaku Yauchihara, Critic

“I think the inscription is excellent. Reflecting on the nature of the evil, pledging never to repeat this evil, these are not easy tasks. But if this is not achieved, the victims of the bombing will never be able to rest in peace.”

Yoshie Hotta, Author

“‘For we shall not repeat the evil.’ Who perpetrated this evil? There are numerous answers. However, if this is a vow made from the perspective of ordinary people, who are always the victims, the words should be: ‘For we shall not allow anyone to repeat the evil.’”

Mitsuo Taketani, Nuclear physicist

“I want to ask the people of Hiroshima: How are you going to prevent the evil from being repeated? How are you going to aid the victims so that they might rest in peace? I think the inscription should be: ‘Don’t sleep; scream out in your graves. The evil may soon be repeated.’”

(Originally published on April 16, 1995)