History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 20, Article 1)

Mar. 11, 2013

Religious Organizations

by Masuhei Ono, Senior Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

Tracing the history of the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, as well as the A-bomb survivors’ movement, religious organizations and labor unions, which helped sustain these efforts behind the scenes, are a regular presence. Among these religious organizations, the Buddhist order “Nipponzan Myohoji,” or the “Japan Buddha Sangha,” stands out prominently. Serving quietly and tirelessly in their yellow robes, the monks of this order bear drums shaped like round paper fans. Through its nonviolent action, the Nipponzan Myohoji Order opened a new horizon for the peace movement in Japan’s Buddhist society. Also making important contributions to these causes have been Quakers and Christians, largely Roman Catholics, who devoted themselves to relief efforts for the survivors of the atomic bombing in the aftermath of the attack and have made persistent appeals for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Meanwhile, among labor unions, the Hiroshima branch of today’s All Japan Construction, Transport and General Workers’ Union is noteworthy for the activities that have amounted to efforts to provide support to A-bomb survivors. In these efforts, one leader lived his postwar life together with workers enrolled in the city’s relief program for the unemployed. Major labor unions in Hiroshima, which formed A-bomb survivors’ organizations within company unions and set the quest for peace and relief for A-bomb survivors as main pillars of their union movement, also played a large role. The Chugoku Shimbun looks back at representatives of these religious organizations and labor unions.

Monks of Nipponzan Myohoji Order pursue peace marches

Two peace marches are now making their way toward the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, one from Auschwitz, Poland, and the other from Tokyo. They are the “Interfaith Pilgrimage for Peace and Life in 1995,” which began with firm steps on the frozen ground of Eastern Europe at the end of last year, and the 1995 version of the “Peace Pilgrimage,” which has put on years calling for nuclear abolition.

Both marches were initiated by monks of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order. The march from Auschwitz has now reached Cambodia, and is led by the Reverend Maha Ghosananda, a Buddhist monk referred to as the “Gandhi of Cambodia.” The procession is scheduled to arrive in Osaka on August 1 and then join the Peace Pilgrimage in Japan. They are expected to reach Hiroshima on August 3.

The Buddhist monks of Nipponzan Myohoji, clad in their yellow robes, loudly chant the words “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo”--“Adoration to the Scripture of the Lotus of the Perfect Truth”--as they beat drums more than 30 centimeters across and pray for peace. What is the Nipponzan Myohoji Order, a name known in conflict areas across the world, including in Africa, the former Yugoslavia, Palestine, and Chechen, places that have suffered from endless gunfire and artillery smoke?

One stop from Shibuya station in Shibuya Ward, Tokyo, on the Inokashira Line, the Shibuya Dojo of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order, more like a hall than a temple, stands surrounded by private homes, inns, and pawnshops in a corner of the Shinsen district. This is the current “headquarters” of the order, which has neither a head temple nor a hierarchy among its monks.

There is no main gate for the Shibuya Dojo, either. Moving through an alley where plants and wild flowers have been casually planted, visitors are abruptly met by a wooden board at the entrance of the hall. When I offered greetings from the outside, a nun welcomed me, joining her hands in prayer and chanting “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo.”

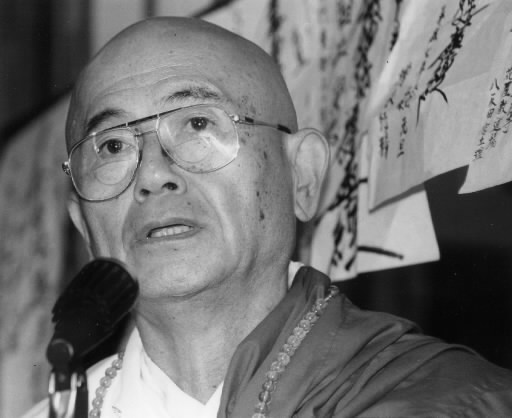

The small room which serves as the study of the Shibuya Dojo is a jumble of books and commemorative tokens. Higai Matsuya, 70, has been the unofficial leader of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order since Nichidatsu Fujii, the founder of the order, died ten years ago at the age of 99. “We will save this degenerate age through a religious practice called Gyakku-Senryo, where we chant ‘Namu Myoho Renge Kyo’ and beat our drums,” Mr. Matsuya told me. “The teachings of the Most Venerable Nichidatsu Fujii are founded on a book entitled ‘Rissho ankoku ron’ [‘On Establishing the Correct Teachings for a Land of Peace’], which was written by Nichiren Shonin, or Saint Nichiren, and states that bringing peace to a nation naturally leads to bringing peace in people’s lives.”

The tenets of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order are very clear: “ahimsa,” the teaching of Buddhism, and direct nonviolent action, as taught by Gandhi. Abiding by these two principles, the monks engage in resistance to military action and violence that lead to bloodshed through the use of nonviolent action. After World War II, they have consistently joined anti-war, anti-nuclear, and anti-U.S. base struggles, standing up to the powers that be.

In the words of Mr. Fujii: “Civilization is not to have electricity nor airplanes, nor to produce nuclear bombs. Civilization is not to kill humans, nor to destroy things, nor to make war. Civilization is to hold one another in mutual affection and respect.”

Mr. Fujii was born into a family of farmers in Kumamoto Prefecture in 1885. After graduating from Nichiren Shu University (now, Rissho University), he learned about Buddhist sects, including the Jodo sect, the Shingon sect, and the Zen sect. He then moved to Manchuria in the northeastern part of China, and opened the first temple of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order in Liaoyang in 1918.

However, it was a temple in name only. In reality, it was a shack made of husks of kaoliang. Ever since, the Nipponzan Myohoji Order has adopted principles which include the absence of formalities, parishioners, and wives. Parishioners are avoided because of the concern that their generosity would result in the monks living lives of comfort, with warm clothes and ample food. And taking wives is deemed incompatible with the order as married life may lead to financial woes.

As an aspect of their training, the monks of the order are invariably on the streets. They travel on foot and make pilgrimages, remaining open to the public. They believe that, by adhering to formalities, or settling down in one spot, a person’s spirit is prone to corruption. With “Rissho ankoku ron” upholding the Nipponzan Myohoji Order, the monks immerse themselves in endless self-discipline.

There are deep ties between the Nipponzan Myohoji Order and the city of Hiroshima. The first peace march between Hiroshima and Tokyo, staged in 1958, when the nascent movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs was gaining great strength, was proposed by Atsushi Nishimoto. Mr. Nishimoto was a monk from the order who died in a traffic accident in 1962. The peace march, which was led by monks of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order, became a model for the group’s subsequent peace activities.

Takao Takeda, 46, who has taken part in the peace march between Hiroshima and Tokyo every year and will mark his 14th march this year, said, “As someone who was given the chance to go on living, joining a march that appeals for peace is the least I can do. If I didn’t make these small efforts, I’d feel guilty...” Mr. Takeda devotes much of his time throughout the year to participating in such peace pilgrimages, starting with a march from Tokyo to Yaizu in February, Tokyo to Hiroshima from May to July, and in Okinawa in October.

The Interfaith Pilgrimage for Peace and Life, which began in Auschwitz, was the brainchild of Gyoshu Sasamori, 44. The pilgrimage departed Auschwitz last December 8. By the time it reached India at the end of March, via the former Yugoslavia, Palestine, and Iraq, among other places, the number of marchers had grown to 108. This is the Nipponzan Myohoji Order’s second pilgrimage between Hiroshima and Auschwitz, following the 1962-1963 march led by Gyotsu Sato, 76, who has already left the order.

The marchers, mainly Japanese and Americans, consist of various nationalities and religions. They also come from different walks of life, including a Vietnam War veteran, Korean brothers residing in Japan, and a former newspaper reporter from Japan. By taking part in the peace march, the participants ennoble their inner selves and, at the same time, pray for the realization of peace in the world.

Commanding a view overlooking the city of Hiroshima, a 25-meter-tall “peace pagoda” stands at the top of Mt. Futaba. With a base that is 20 meters in diameter, the pagoda is plated with stainless steel and dazzles when the sunlight strikes it. In 1953, eight years after the atomic bombing, Nichidatsu Fujii visited Hiroshioma and called for the structure to be built. However, differences of opinion with local business leaders, who had also been hoping to construct a peace pagoda in the city, created a wrinkle which delayed the realization of the pagoda for many years. In the end, the locally-backed pagoda did not come to fruition and the pagoda supported by the Nipponzan Myohoji Order was completed in 1966.

At the Buddhist service to inaugurate the peace pagoda, the late Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai addressed the participants with these words: “The key to realizing the idea of building a peace pagoda lies in a solemn vow. It’s now very clear to me that simply listing the names of high-ranking officials and financial associations isn’t nearly enough.”

The Hiroshima Dojo, or Hiroshima branch, of the Nipponzan Myohoji Order is located halfway up Mt. Futaba. Gyoko Kawagishi, 48, has served as the chief priest for 19 years. In 1980, he helped lead a pilgrimage for world peace, walking from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to India and Cambodia over the course of seven months. As a result of the march, he developed liver and heart troubles. Gazing into the distance, Mr. Kawagishi said, “Because of my health, I couldn’t continue walking. If I could regain my health, I’d like to go on another march...”

The Nipponzan Myohoji Order now has 30 temples in ten nations, including India, Sri Lanka, the United States, and the United Kingdom, as well as 120 temples in Japan. About 200 monks belong to the order. One monk fell victim to the ethnic fighting in Sri Lanka, while another monk became ill and died during a peace pilgrimage.

Mr. Matsuya, the head of the order, told me, “With our belief in the teachings of Nichiren Shonin, we are singleminded in our chanting and walking, wishing for peace, not holding our own lives dear. Our heads aren’t thinking about these things. If we start thinking, the outcome of our efforts will be no different from the ordinary peace movement pursued by the general public.” Singleminded prayer, to the point of sacrificing one’s own life, is considered extreme--and yet religions were originally “extreme” in this same way. Over time, and without our awareness, religions in Japan have been reduced to ceremonial rites for funerals and weddings.

On May 4, at a gathering to mark his 70th birthday, held at the Shibuya Dojo, Mr. Matsuya put his feelings into this poem: “Drawn by the young monk’s desire to follow the Buddhist path, not holding his own life dear, I continue on my way.”

Pedro Arrupe, “The Black Pope,” devotes himself to treating A-bomb survivors

Successive Popes have shown a special interest in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. In particular, the current Pope, John Paul II, was the first Pope to come to the city. He left a powerful impression on the Japanese people, including the citizens of Hiroshima, during his visit in 1980.

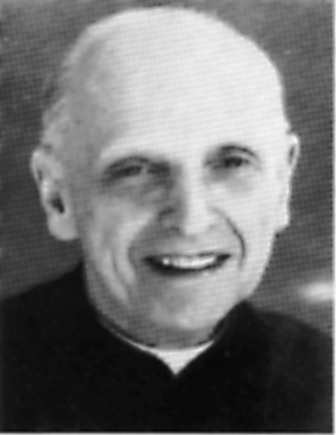

Pedro Arrupe, the Superior General of the Society of Jesus, spoke to Pope John Paul II about the horrific consequences of the atomic bombing. Few people know that Father Arrupe, a leading figure in the Roman Catholic world, was one of the foreign missionaries who treated injured A-bomb survivors in the chaotic aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima. As a result, deep gratitude was felt toward the cleric.

Father Arrupe, a Spaniard, came to Japan in 1938. Four years later, in 1942, he became the rector of the Nagatsuka Monastery for Jesuits in Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima, an outlying area of the city. On the day of the atomic bombing, the novitiate was hit by an intense blast that shattered every window on the south side of the building and blew off the doors.

Luckily, only one person at the monastery was injured, with wounds to his face from flying fragments of glass. Shortly, however, as many as 80 people suffering from severe burns streamed into the building.

The library, the common room, and the chapel were turned into spaces to treat the wounded, and the rector’s study became a makeshift operating room. Father Arrupe, who had a medical background, took the lead in the monastery’s efforts to treat the A-bomb survivors. The clerics covered the wounds with gauze, moistened the gauze with a boric acid solution, and kept the wounds clean. The treatment they provided was reportedly effective and, among the injured housed at the novitiate, just one person died.

In 1954, Father Arrupe became Jesuit Vice-Provincial for Japan and moved to Tokyo. In 1965, he assumed the post of Superior General of the Society of Jesus, the highest position in the organization, and then left Japan. Serving in that position until 1983, he reformed the Society of Jesus from a traditional monastic order to a new religious order, adopting new theology and an orientation toward social justice.

He was a man of such influence that he was even compared to the Pope, with some referring to his black cleric’s robe of the Society of Jesus in dubbing him “The Black Pope.” He died in 1991 at the age of 83.

Father Tadashi Hasegawa, 64, who received treatment from Father Arrupe and was able to cheat death, now serves as a priest at Catholic Tamano Church in Okayama Prefecture. Last year he visited Father Arrupe’s grave on the outskirts of Rome. Father Hasegawa cherishes the memory of Father Arrupe: “I had suffered severe burns over half of my body, and my condition was critical a number of times, but Father Arrupe was a miracle worker. As I couldn’t forget what he did for me, I became a priest of the Diocese of Hiroshima, too. Father Arrupe was a great cleric.”

The fact that the Society of Jesus treated roughly 100 A-bomb survivors and that foreign missionaries devoted themselves to the care of the injured has been completely ignored when it comes to the history of the atomic bombing. Those who did great good for the A-bombed city of Hiroshima existed in such stratums of society, too.

(Originally published on June 4, 1995)