History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 22, Article 2)

Mar. 13, 2013

Mayors and local government II

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

Hiroshima’s postwar mayors shoulder the city’s mission and its obligations as an A-bombed city. Six people have served as mayor. Shinso Hamai, the city’s first popularly elected mayor, created the framework for postwar Hiroshima, maintaining that the atomic bomb could lead to the extermination of the human race and laying the foundation for the city’s rebuilding. He oversaw the inauguration of the Peace Memorial Ceremony, the construction of Peace Memorial Park and the preservation of the A-bomb Dome. “We must dedicate ourselves to what has to be done now and forge a path toward peace,” he said. This article looks at Mr. Hamai’s wishes, which still prevail today, and the calls for peace issued by the mayors who succeeded him in their peace declarations. Also, Hitoshi Motoshima, former mayor of Nagasaki, was asked about his view of Hiroshima from Nagasaki.

While sometimes wavering or coming in for criticism amid the changing times, Hiroshima’s mayors and the local government have continued to work toward peace, and those efforts represent the history of Hiroshima’s citizens as well.

Obligation to assist victims of radiation

Hiroshima as seen from Nagasaki: Hitoshi Motoshima

“Mayors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki can’t avoid the issues of the atomic bombings and peace,” said Hitoshi Motoshima, 73, during an interview in that city in late May. His friendly smile and way of speaking were memorable. Mr. Motoshima, who served as mayor for 16 years through April, was asked about his perspective on Hiroshima.

How do you regard Hiroshima’s message and its actions?

Nagasaki was quiet. One reason is that the destruction in Nagasaki was less extensive than in Hiroshima. And a lot of the atomic bomb survivors, including me, were the descendants of secret Christians. They accepted the A-bombing as divine providence and didn’t speak out. Meanwhile, with the enactment of the two atomic bomb-related laws (the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law and the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law) for example, Hiroshima’s local government, A-bomb survivor organizations, universities and news media elicited support. In terms of getting the message across, Hiroshima is our big brother.

What are your impressions after associating with that “big brother”?

Here people always say “Hiroshima, Nagasaki.” We have always mentioned them together, but Hiroshima seldom says anything about Nagasaki. For example, the area damaged by the atomic bomb in Nagasaki is a sort of oval extending 12 km north and south and 6 km east and west. We were going to ask the central government to make a correction, but when we submitted our request to the Council of Eight (the Hiroshima-Nagasaki Council for the Promotion of Relief Measures for A-bomb Survivors, made up of the city and prefectural governments of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and their assemblies), it was rejected. While I was mayor I learned from news reports that Hiroshima is going to submit an opinion ad for publication in a U.S. newspaper this summer. That is unacceptable.

In March, shortly before you stepped down as mayor, you gave a speech at a meeting of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan that you attended with the mayor of Hiroshima. You caused an uproar when you said that the use of the atomic bomb ranked with the Holocaust as one of the greatest crimes of the 20th century.

I’m not saying that President Truman was as bad as Hitler, but the atomic bomb is an evil weapon that threatens the existence of the human race. So what I said was that its use constituted two serious crimes. I stated my thoughts accurately. It was the same with my comment on the emperor’s responsibility for the war. But for some reason in my case it stirs up controversy.

Even after you were shot for making that comment, some people in Hiroshima said that public figures should not openly express their personal opinions.

That is a perfunctory argument. Isn’t Japan’s responsibility for the war perfectly clear? Why were there people who were rejoiced when the atomic bombs were dropped? We have to consider the bombings in light of that. The annexation of Korea, the Sino-Japanese War – the reason I included Japan’s history of invasion and an apology in the Peace Declarations as well is that I considered what led up to the A-bombings.

So you feel that point of view has been lacking in Hiroshima?

Well, if we don’t look at the atomic bombings in the context of the war rather than starting with the A-bomb Dome, our message won’t get through to Asia and we won’t be able to bridge the gap between the U.S. and Japan. In the past the board of directors of the World Conference of Mayors for Peace through Inter-city Solidarity just talked about the abolition of nuclear weapons and clashed with other cities, so it was sometimes difficult to put proposals together.

Nagasaki has a committee for the drafting of the peace declaration that includes ordinary citizens, and you have disclosed the process involved in drafting the declaration to the public via the news media.

I’m not an atomic bomb survivor, so it’s important that I get opinions from various people. Including Japan’s invasions and an apology for them in the declaration came about as the result of those discussions. But I wouldn’t talk about the pros and cons of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty or the production of weapons. If I did, discussion would end immediately.

Finally, what would you like to see Hiroshima do in the future?

We have the same goals, so my hope is that we can work hand in hand. If Hiroshima’s message is consistent with that of Nagasaki, it will be more powerful and we can join hands with radiation victims throughout the world.

Hitoshi Motoshima

Born in the Goto Islands of Nagasaki Prefecture. During the war served in an army training corps in the Western Military District in Kumamoto. Graduate of Kyoto University. After working as a teacher at a night junior high school, served five terms in the Nagasaki Prefectural Assembly. Elected mayor in 1979. At a city council meeting in 1988 stated that he believed the emperor bore some responsibility for the war and was seriously injured when subsequently shot by the leader of a right wing group. Unseated in the mayoral election in April of this year.

[History of Hiroshima’s Peace Declaration: Renunciation of war, souls of the dead, violations of international law]

The Peace Declaration read by the mayor at Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Ceremony is regarded unenthusiastically by some as an essay by bureaucrats. But etched into the declarations that have been delivered for nearly 50 years are views of the time on the atomic bombing, a commitment to peace and efforts to bring it about. The language of the declarations also reflects the thinking and personalities of past mayors. This article examines changes in the message of Hiroshima over the years as shown in the Peace Declaration.

▽Shichiro Kihara (October 1945 – March 1947)

Mayor Kihara attended the Peace Restoration Festival sponsored by the federation of town councils, which was held on August 5, 1946, the day before the first anniversary of the atomic bombing. In the declaration he read at the festival Mr. Kihara pledged “the prompt and peaceful rebuilding of civic life, which was completely destroyed.” The city was in ruins referred to as the “atomic desert.” Mr. Kihara was the last mayor appointed by imperial order via the Ministry of the Interior.

▽Shinso Hamai (April 1947 – April 1955)

Hiroshima’s Peace Declaration began with the Peace Festival, which first took place in 1947.

In his declaration on that occasion Mr. Hamai said, “…Hiroshima turned into a city of death and darkness. Yet as some slight consolation for this horror, the dropping of the atomic bomb became a factor in ending the war and calling a halt to the fighting.” At the time, Japan was under occupation. This statement by the mayor echoes the U.S. theory on the dropping of the A-bomb that still holds sway there. But the survivors of the bombing must have wondered if that was the only way to give meaning to the tremendous sacrifice that was made.

At the same time, the mayor warned that the A-bomb was a weapon that could lead to the end of the human race declaring, “…the people of the world have become aware that a global war in which atomic energy would be used would lead to the end of our civilization and extinction of mankind.” He also called on people in Japan and around the world to “to sweep away from this earth the horror of war, and to build a true peace.” Herein lies the origin and the spirit of the Peace Declaration.

The Korean War broke out in June 1950, and the ceremony was cancelled that year. Starting the following year the Peace Festival took the form of a ceremony to honor the victims of the bombing and a peace memorial ceremony, but the declaration was shelved, and the mayor merely delivered brief remarks.

In 1952, the Allied Occupation ended and the cenotaph for the A-bomb victims was completed. In his declaration the mayor said, “We offer a sincere pledge before the souls of the victims of the A-bomb.” And in subsequent years a pledge to the souls of the victims to work toward peace became an established part of the declaration.

▽Tadao Watanabe (May 1955 – May 1959)

On the 10th anniversary of the A-bombing, the first specific reference to the plight of the survivors was made when the mayor said, “Six thousands of those who are suffering from A-bomb aftereffects are not still entitled to receive proper medical treatment.”

With the contamination resulting from the nuclear test on Bikini Atoll in 1954, there was a growing call for a ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs. The peace declaration belatedly addressed this issue in 1958 when the mayor called for “…the creation of a stronger public opinion, to exert ourselves for the establishment of an international agreement on the complete outlawing of the manufacture and use of all nuclear weapons.” This was the first clear reference to a total ban on atomic and hydrogen bombs. Mr. Watanabe was a former member of the Diet from the Liberal Democratic Party.

While taking twists and turns, by this time the declaration included the three pillars of today’s declarations: a pledge to seek peace, a memorial to the victims of the bombing, and a target of nuclear weapons abolition. The declarations made around 1958 were very brief.

▽Shinso Hamai (reelected) (May 1959 – May 1967)

Nuclear tests were conducted by France in 1960 and by China in 1964, making all five members of the U.N. Security Council nuclear nations. There was a struggle for supremacy between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and the Vietnam War dragged on.

On the 20th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Mr. Hamai, who had resumed the post of mayor, noted that the radioactivity of the bomb had been “undermining human bodies over a long period of time” and called for “the banning of atomic and hydrogen bombs and for the complete renunciation of all war.” Just prior to that, he expressed the desire that Prime Minister Eisaku Sato would deliver a peace declaration.

▽Setsuo Yamada (May 1967 – January 1975)

Mayor Yamada had been an advocate of a world federation since the end of the war, and he had also served as vice chair of a confederation advocating the establishment of a world federation. In 1967 he called for “a new world order where Law shall prevail.”

In 1968 he directly criticized the theory of nuclear deterrence saying that “to regard nuclear weapons as an effective war deterrent will only serve to spur the nuclear race.” This led to a style of declaration in which appeals were made from the viewpoint of a “global Hiroshima.” Starting in the 1970s the declarations began to include specific requests to the Japanese government as well as the United Nations.

The declaration made the first reference to U.N. activities in 1972, and in 1974 the mayor said, “In order to decisively put a stop to the precarious headway of nuclear proliferation, we will appeal to the United Nations to convene an urgent international conference for an early conclusion of a total nuclear ban agreement, including all nuclear possessing nations.” The declaration also called for prompt ratification of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, which Japan had signed in 1970.

The “promotion of peace education” and the “heart of Hiroshima,” expressions that are still used today, made their appearance in the declaration in 1971 and 1972, respectively. One feature of the declarations at that time is their lack of a reference to support for the atomic bomb survivors.

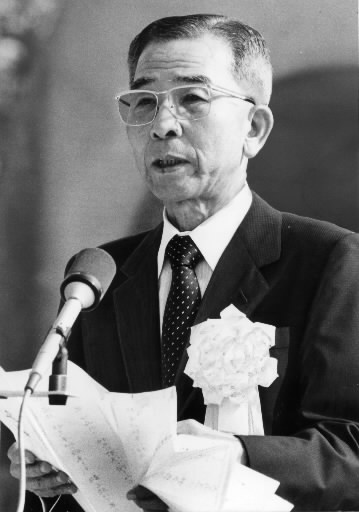

▽Takeshi Araki (February 1975 – February 1991)

During this time the declarations began stressing appeals to the United Nations for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the significance of abolition. Mr. Araki was 3.5 km from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing.

In 1977 the mayor referred to a visit he and the mayor of Nagasaki had paid to Kurt Waldheim, secretary-general of the United Nations. “We took with us an ardent wish which had been smoldering over the years in the hearts of our citizens. There we, as survivors, living witnesses, testified the true facts of our atomic bomb experiences.” In 1978 the mayor stated the significance of the first U.N. Special Session on Disarmament. And in 1982, referring to the nuclear arms race that was taking place between the U.S. and the Soviet Union in Europe he said, “Furthermore, we propose that the leaders of the nuclear powers and other nations should visit Hiroshima to confirm the true nature of the disaster of the atomic bombing.” The mayor also called for the establishment in Hiroshima of an institute for the study of world peace and disarmament. Mr. Araki visited United Nations headquarters five times.

On the 40th anniversary of the A-bombing, Mr. Araki urged collaboration with cities around the world and called for “added momentum to the international quest for peace.” In 1986 he broadened his message, saying, “…peace suffers from the growing specter of starvation, the plight of refugees worldwide, the denial of human rights, and other affronts to human decency.” The Berlin Wall fell in 1989, and in 1990 the U.S. and the Soviet Union agreed to reduce their strategic nuclear arsenals.

In that year’s Peace Declaration the mayor called on Japan for positive diplomatic measures “to pass the three non-nuclear principles into law” and “to take the initiative in making the Asia-Pacific region a nuclear-free zone of disarmament.”

The message also included a request for assistance for the atomic bomb survivors. With the government’s reconsideration of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law and the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law, in 1980 the mayor declared, “We express our desire for the earliest enactment of the A-bomb victims’ relief law, based on the acceptance of national responsibility for indemnity.” But enactment of the law was rejected based on the idea that A-bomb survivors should be treated in a way that maintained balance with the treatment of other victims of the war. So he toned down his message and refrained from using the word “enactment,” instead calling for “expanded and strengthened relief measures” in 1981.

At their lengthiest, the declarations extolled the “heart of Hiroshima” while repeatedly stating that Japan was the only nation to have been A-bombed. Those declarations failed to mention the existence of atomic bomb survivors in South Korea and other countries, those who were exposed to radiation as the result of the nuclear accident in Chernobyl or nuclear tests or the issue of support for them.

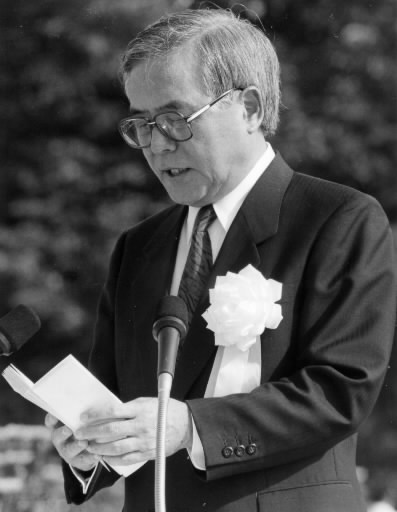

▽Takashi Hiraoka (February 1991 – present)

In 1991, the year he became mayor, Mr. Hiraoka became the first to refer to and apologize for Japan’s aggression saying, “Japan inflicted great suffering and despair on the peoples of Asia and the Pacific during its reign of colonial domination and war. There can be no excuse for these actions.”

He also said, “Hiroshima has begun to extend medical assistance to the victims of Chernobyl and other nuclear disasters, but their numbers are vast indeed. Thus it is that, taking this leadership initiative, Hiroshima is calling for an international relief effort for these people.” It was also the first year in which the term “Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law” was used in the declaration.

In May of this year the indefinite extension of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty was approved, but in his 1994 declaration the mayor declared, “…we are opposed to the indefinite extension of a Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty that makes no clear provisions for the elimination of nuclear weapons...” With regard to judicial rulings on the use of nuclear weapons as well, he drew a line between the city’s view and that of the central government saying, “Nuclear weapons…are patently illegal under international law. This is something that the hibakusha know from personal experience.” In this way he clearly stated Hiroshima’s stance on the issue.

As long as there are nuclear weapons, there will be Peace Declarations.

(Originally published on June 18, 1995)