History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 23, Article 1)

Mar. 14, 2013

Protests against nuclear tests

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

As a child, I was horrified by the idea of “radioactive rain.” At the time, there was talk that the sky above Japan was scattered with contamination as a result of radioactive fallout from nuclear tests. I felt so helpless when I got caught in the rain. I remember tugging gently on my hair, seeing if it would come out in my hand.

During the Cold War era, the appalling nuclear arms race drove humanity to the brink of annihilation. A total of more than 2,000 nuclear tests were conducted by the nuclear powers. The A-bombed cities voiced anger at the reckless actions which threatened our very survival, while the world’s conscience sparked a range of protests, including sit-in demonstrations and the dispatch of ships as a gesture of protest against nuclear testing. Both forms of protests adhered strictly to the non-violent philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi. The success gained in confining nuclear tests underground, bringing those in the atmosphere and underwater to a halt, was no doubt a victory of public opinion.

The collapse of the Cold War dynamic has advanced the cause of nuclear disarmament. Still, nearly 45,000 nuclear warheads remain in the world today, and some nations press ahead with nuclear tests. The desire of those who have demonstrated their wishes to eliminate nuclear weapons through their actions has yet to be realized.

Earle Reynolds sets sail on worldwide anti-nuclear efforts

He now lives quietly in a nursing home near Los Angeles. His occasional walks are said to be his only contact with the world outside. His memories, too, have grown distant. One photo hangs on the wall: a yacht sailing the vast waters of the South Pacific. Manning the deck is Dr. Earle Reynolds, sporting a smile on his tanned face, a vigorous presence.

Dr. Reynolds is now 84. In 1958, he was arrested for attempting to enter the site of a hydrogen bomb test taking placing at the Enewetak Atoll, located in the central Pacific Ocean. From that point on, sailing aboard “The Phoenix,” the yacht he cherished, Dr. Reynolds made a series of “forbidden voyages” to the Soviet Union and war-torn Vietnam. Dubbed a “fighter for peace,” he put forth words and deeds that had a significant impact on the peace movement internationally.

In 1951, Dr. Reynolds was transferred to the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), located in Hiroshima, to conduct research on the effects of A-bomb radiation on the growth of children who had been exposed to the bomb. At the time, he was frowned upon by A-bomb survivors due to his work. Simply pursuing his research resulted in hurt feelings among the children, when they were photographed naked. Dr. Reynolds himself became haunted by the enigmatic horror of atomic weapons as he carried out his work. Still, he did not yet hold distinct anti-nuclear feelings. But then an American soldier’s words during lunch one day came to linger in his mind. The soldier said that they had feared the “Japs” might surrender before they had a chance to try out the Nagasaki-type bomb, too.

After his three years of service at ABCC ended, Dr. Reynolds boarded his boat for a round-the-world voyage. Though he was an amateur sailor, the trip had been a childhood dream. While some criticized the voyage as reckless—and an experienced yachtsman refused to board the boat just before its departure—The Phoenix left Hiroshima port with four members of his family and three young Japanese nationals.

Sailing with the trade winds, the yacht made port calls in Hawaii, Jakarta, Sydney, and Cape Town. They gave talks about Hiroshima at these ports, and interacted with the local people on smaller islands en route, the names of which they did not know. With the word “HIROSHIMA” adorning the boat, the curiosity of local residents was piqued and they asked about the consequences of the atomic bombing. As the Japanese on board responded, Dr. Reynolds and his family listened quietly from the cabin. It was the first time for the family to hear directly from survivors of Hiroshima. Dr. Reynolds and his family were surprised at the fact that the horror of the atomic bombing had touched every corner of the world.

In May of 1958, The Phoenix made another stop in Hawaii. Three years had passed since the boat left Hiroshima, and Honolulu was now abuzz with rumors involving a yacht called “The Golden Rule.” The boat had been brought back to Honolulu by the Coast Guard the previous day, after seeking to trespass onto a restricted nuclear test site in order to try preventing a U.S. hydrogen bomb test.

The Golden Rule crew, who were Quakers, sought permission in court to sail into the restricted zone. One of them told the judge that when the laws of his government did not agree with the laws of God, he must obey God. They could arrest him and put him in jail, he said, but they could not imprison his conscience. Dr. Reynolds and his wife Barbara, who were in the courtroom to observe the proceedings, were deeply moved. The couple realized that a vague desire in their minds had begun to take clear shape.

They discussed the idea that night and Barbara expressed a firm determination. She said that a nuclear test site lay along their route—the route of a boat built in Hiroshima—and that God was now speaking to them. But Dr. Reynolds could not make such a decision as easily. In the ship’s log, he wrote about his feelings, relating how he had been born into a poor family, but worked hard and attained a position that he had thought highly improbable. He hesitated to abandon all that he had achieved over the years.

Dr. Reynolds was also reluctant to put their children, and the Japanese crew members, in danger. But his daughter Jessica, then 14, told him that the world was hers, too, and she had just as much right to fight for it as her father and mother. The late Niichi Mikami, then 34, one of the Japanese nationals on board, expressed his resolve as well, citing his Japanese roots. At that point, Dr. Reynolds was persuaded and hesitated no longer.

At midnight on the 23rd day following their departure from Honolulu, they came upon a towering black warship that blocked their way. A dark silhouette shouted to them, asking if they sought to enter the off-limit zone. Remaining on its course, The Phoenix would enter the restricted waters around 8 p.m. the following day. Dr. Reynolds shouted back this intention. The warship then trailed the boat at a distance of about one mile, or about 1.6 kilometers. Using his radiotelephone, he announced on the international frequency for ships at sea: “The United States yacht Phoenix is sailing today into the nuclear test zone as a protest against nuclear testing.” It was July 1, 1958. A “fighter for peace” was born on that day. The following morning, 85 miles inside the forbidden area, The Phoenix was ordered to stop, and Dr. Reynolds was arrested.

Dr. Reynolds was brought back to Honolulu and, on the day he arrived, was found guilty and sentenced to two years in prison, with the sentence suspended for 18 months. For the next two years he lived aboard The Phoenix, moored at port, and pursued his legal battle, defending his voyage with the principle of “freedom of the seas.”

The late writer Toko Kon shared his impressions of meeting Dr. Reynolds in the October 1959 issue of Bungei Shunju, a leading monthly magazine in Japan: “Looking at his tanned face and grasping his hand, I couldn’t stop the tears from coursing down my cheeks. I felt I was seeing the sincere goodwill of human beings and had found true democracy in this man.”

The protest, pursued by Dr. Reynolds and his comrades, who were willing to suffer personal loss as a consequence of their actions, stirred the conscience of the world. Letters of encouragement and financial support for his legal battle arrived daily at The Phoenix. At the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, Dr. Reynolds finally won acquittal.

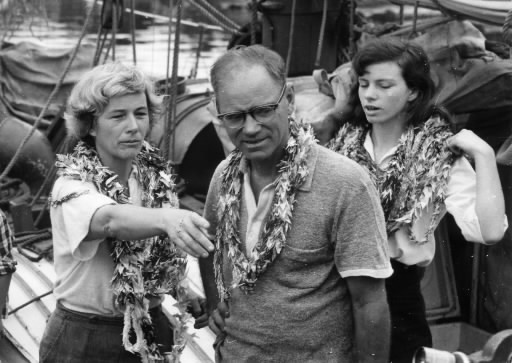

Setting sail for Japan, Dr. Reynolds finally glimpsed the homes and streets of Hiroshima after an absence of five years and nine months. A large contingent of citizens turned out on the pier to greet The Phoenix. Among them were children from the “Hiroshima Paper Crane Club” and Ichiro Kawamoto, now 66, the leader of the group and a resident of Naka Ward. A year before The Phoenix left Hiroshima, Mr. Kawamoto was slated to board a ship planning to protest a U.K. hydrogen bomb test. The action was organized by the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, but was canceled.

At the pier, with fewer well-wishers now in attendance, the children sang the song “No A Bomb.” Dr. Reynolds, listening closely, made a decision. Several days later, he and Barbara went to see Mr. Kawamoto and told him they wanted to learn more about the A-bombed city. The couple began paying visits to A-bomb survivors, offering comfort, alongside children of the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club.

This interaction with Hiroshima citizens, which Dr. Reynolds lacked during his tenure at ABCC, sharpened his spirit as a peace activist and he made plans to establish the Hiroshima Institute of Peace Science (HIPS). At this time, August of 1961, the Soviet Union announced its intention to resume its nuclear testing. In response, Dr. Reynolds immediately declared that he would dispatch his boat to stage a protest. Previously, he had made a protest against his mother country; this time he would pursue a protest against the Soviet Union. Contingencies, including the possibility that they could be charged with spying, were anticipated. And though public opinion over this issue was divided, Dr. Reynolds did not back down.

Ten miles off Nakhodka, The Phoenix was ordered to stop. The Soviet side refused to accept the peace messages that Dr. Reynolds had brought from Hiroshima citizens. His crew now had no choice but to return to Hiroshima. On their way back, the boat was hit by a storm and it ran aground, among other troubles. The rough sailing turned out to be a harbinger of future difficulties that Dr. Reynolds would face from that point forward.

After returning to Japan, Dr. Reynolds immersed himself in preparations for the Hiroshima Institute of Peace Science. A man of quick action, he did not find comradery with Japanese scholars, who were academics more inclined to pursue research in their disciplines. Putting up a solitary fight from a small office in the Kamiyacho district, Dr. Reynolds wrote tirelessly about conditions in Hiroshima to peace institutes across the world and spoke about the A-bombed experiences on lecture tours.

In the process, the marriage of Dr. Reynolds and his wife Barbara, who loved and respected one another, came to a sad end. People pointed an accusing finger at Dr. Reynolds, in part because he later married a Japanese woman. As if to shake off his pent-up emotion, Dr. Reynolds again boarded The Phoenix. Loading medical supplies onto his yacht, he headed for Haiphong to bring aid to North Vietnamese citizens who were injured in bombings by U.S. forces. In Hanoi, Dr. Reynolds proudly stated that he had come to Vietnam to help create a world without war. But this voyage led both the Japanese and U.S. governments to consider Dr. Reynolds a security risk.

In May 1970, this “fighter for peace” boarded his beloved yacht again, this time with a cheerless countenance. He said that the climate that warmly welcomed peace activists had become a thing of the past in Japan. Charged with violating the Immigration Control Ordinance after a voyage to China, which was intended as a gesture of friendship and reconciliation, he was expelled from Japan. Seen off by acquaintances, The Phoenix quietly pulled up anchor.

Dr. Tomin Harada, 82, a resident of Naka Ward and an associate of Dr. Reynolds, said, “Hiroshima has never adequately acknowledged Dr. Reynolds’s dedication to the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. Creating a peace institute was a progressive idea. In a way, it may have failed only because he was a pioneer.” After returning to the United States, Dr. Reynolds taught peace studies at a university in California. But he never boarded his boat again as a fighter for peace.

Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., the leader of the U.S. civil rights movement, praised Dr. Reynolds as a pioneer for peace on a par with Mahatma Gandhi. The seeds sowed by this pioneer have now sprouted, and the ships of various organizations have appeared to stage protests against nuclear tests. Today, too, new “fighters for peace” are sailing the waters of the South Pacific, at top speed, to protest a French nuclear test planned for the Moruroa Atoll.

[References]

The Forbidden Voyage by Earle Reynolds

The Phoenix and the Dove by Barbara Reynolds

(Originally published on June 25, 1995)