History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 23, Article 2)

Mar. 14, 2013

Protests against nuclear tests

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

As a child, I was horrified by the idea of “radioactive rain.” At the time, there was talk that the sky above Japan was scattered with contamination as a result of radioactive fallout from nuclear tests. I felt so helpless when I got caught in the rain. I remember tugging gently on my hair, seeing if it would come out in my hand.

During the Cold War era, the appalling nuclear arms race drove humanity to the brink of annihilation. A total of more than 2,000 nuclear tests were conducted by the nuclear powers. The A-bombed cities voiced anger at the reckless actions which threatened our very survival, while the world’s conscience sparked a range of protests, including sit-in demonstrations and the dispatch of ships as a gesture of protest against nuclear testing. Both forms of protests adhered strictly to the non-violent philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi. The success gained in confining nuclear tests underground, bringing those in the atmosphere and underwater to a halt, was no doubt a victory of public opinion.

The collapse of the Cold War dynamic has advanced the cause of nuclear disarmament. Still, nearly 45,000 nuclear warheads remain in the world today, and some nations press ahead with nuclear tests. The desire of those who have demonstrated their wishes to eliminate nuclear weapons through their actions has yet to be realized.

Sit-in protests at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims: Defiance to remain seated at starting point of anti-nuclear movement

The buzz of students visiting Hiroshima on school trips had faded away. Silence now enveloped the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. On June 16, a sit-in protest was staged for an hour, starting at noon, to demonstrate against the French announcement that it would resume its nuclear testing. During a lull in the rainy season, the sun beat down on the heads of peace activists and the lined faces of aging A-bomb survivors, among others, who took part in the protest.

“This era, in which the whole human race is threatened with annihilation, is not yet over,” said Akira Ishida, 67, the chair of the A-bombed Teachers Association of Japan, speaking to 52 people sitting on the stone pavement. “The average age of the A-bomb survivors is now 66. In another five years, we will approach the limit of our activities. The A-bomb survivors have a duty to exert ourselves to eliminate nuclear weapons from the world within this century at any cost.”

Such sit-in protests have been held each time a nuclear test is conducted. Some criticize this type of protest as powerless when sized up against the cold and ruthless nature of international politics. However, the sight of A-bomb survivors seated on the stone pavement, like ascetic Zen monks, is a symbolic expression of the A-bombed city’s anger against the nuclear arms race. The scene constitutes, as well, an unspoken wish for the survival of the human race.

The first sit-in protest in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims was staged on March 25, 1957. Kiyoshi Kikkawa, Shoichi Minami, and Ontetsu Kobayashi, now all deceased, as well as Ichiro Kawamoto, began the protest by singing the song “No A Bomb” and calling for a halt to the first hydrogen bomb test planned for Christmas Island, located in the South Pacific, by the United Kingdom.

Reflecting on that first protest, Mr. Kawamoto said, “Sitting with our backs against the cenotaph expressed Hiroshima’s message of protest alongside the A-bomb victims.” Mr. Kawamoto had also volunteered to board a ship that would head toward Christmas Island as a gesture of protest against the nuclear test, an effort organized by the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. “Mr. Kikkawa invited me to take part, suggesting that we do what we could in Hiroshima first, then saying I could give my life for this cause while on the voyage, if that’s what I wanted,” Mr. Kawamoto recalled.

There was a spirited reaction to the sit-in protests at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. Citizens volunteered to join the demonstrations, and a flurry of gifts arrived to encourage the protesters. On April 20, against the backdrop of surging anti-nuclear opinion among the public, a rally by Hiroshima citizens to call for an end to atomic and hydrogen bomb tests took place. The desperate, single-minded actions of the four men had touched Hiroshima citizens, creating a groundswell of support, humble as it was.

Two years later, Mr. Kobayashi was standing before the prime minister’s residence in Tokyo and reading out a letter which protested the rearming of Japan, and then committed “seppuku,” a form of ritual suicide by self-disembowelment.

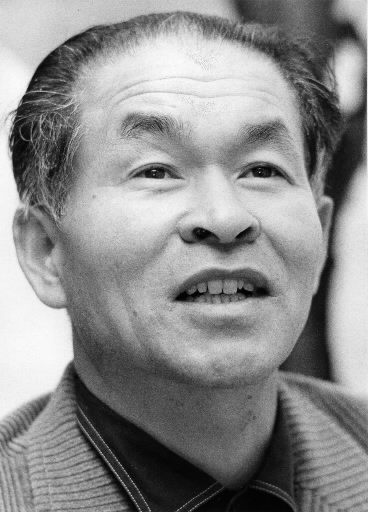

A parasol above his head, the man sat with his white hair perpetually fluttering in the wind. The sight of the late Ichiro Moritaki, then professor emeritus of Hiroshima University, sitting in the front row of protesters became a symbol of the sit-in demonstrations. The aging philosopher took part in his first sit-in on April 20, 1962. This came at a time when the situation involving U.S. and Soviet nuclear tests, which had been suspended, took a turn for the worst. The day before his first sit-in protest, Mr. Moritaki wrote in his diary: “There is news that the United States will soon conduct a nuclear test. The decision has been made to hold an emergency board meeting, with larger numbers [of the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs] tomorrow morning. I helped arrange the meeting. This is the eve of a critical decision.”

This decision involved submitting his resignation to the university and sitting down before the cenotaph with Mr. Kikkawa and the other protesters. Mr. Moritaki shared his sentiments with the Chugoku Shimbun at the time: “If the United States begins to pursue nuclear tests, the Soviet Union will follow suit. I conducted a campaign to collect signatures. I held a gathering. I sent letters of protests. There’s nothing more I can do now but plant myself here.”

Despite suffering from exhaustion and mild sunstroke, Mr. Moritaki maintained a silent protest for 12 days. One day, he watched a girl walking back and forth in front of him. As if summoning the courage to speak to him, the girl said, “I don’t think you can stop the nuclear test by just sitting here.”

The implication was that he should go to the nuclear test site itself and be willing to lay his life on the line to stop the test. The girl’s candid remark shook Mr. Moritaki at his core. But as he continued to sit in protest, he arrived at an answer: “The chain reaction of spiritual atoms must prevail over the chain reaction of material atoms.” His conviction that he must persist in a non-violent approach to rouse public opinion against nuclear arms was formed at that time.

Still mulling the girl’s words, Mr. Moritaki continued to take part in sit-in protests at the cenotaph until his death in 1994 at the age of 92. In all, he staged 476 sit-in protests. His final protest, echoing a comment he made to an acquaintance about pursuing his protests until they carried him away in a casket, was held just six months before he died.

On July 20, 1973, a sit-in was organized against France, which had conducted a series of massive nuclear tests in the South Pacific. A total of 130 people from 17 organizations, including the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations and the liaison council of Hiroshima A-bomb survivors of today’s All NTT Workers Union of Japan, joined the protest. Ever since, sit-in protests have been staged in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims whenever a nuclear test is performed. With protest after protest, the sit-in that took place on June 16 [1995], against France, now marks the 486th one.

The mayor of Hiroshima himself once joined a sit-in. On August 27, 1973, then Mayor Setsuo Yamada was offering encouragement to the participants, maintaining their silent protest on the hot stone pavement under the blazing sun, when someone called out to him: “Mayor, why don’t you sit with us?” A-bomb survivors including Kishie Masukawa and Shinobu Hizume, now both deceased, who published a collection of writing by survivors entitled “Hiroshima no Kawa” (“The River of Hiroshima”), also invited the mayor to join the protest.

Mr. Yamada then sat for about ten minutes in the front row. Afterward, he shared his impressions of participating in the sit-in, saying, “For A-bomb survivors, this silent protest is also a form of prayer. I plan to take these compelling actions of Hiroshima citizens into account as I consider the path that the City of Hiroshima should pursue when it comes to peace.” This was the one and only occasion that a mayor of Hiroshima has taken part in a sit-in.

With the thaw of the Cold War, which had pitted the United States and the former Soviet Union in a nuclear arms race, the number of nuclear tests has declined markedly. China, however, has continued conducting nuclear tests while, in France, there is a move to resume its nuclear testing program. There is also ominous silence in North Korea, Israel, and Pakistan, all of which are under a cloud of suspicion with regard to nuclear weapons development. It will be some time, it seems, before the sit-in protests in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims come to an end.

In introducing this article, I compared those sitting on the stone pavement to Zen monks. One day, an elderly sightseer had the same impression, telling Mr. Moritaki he resembled an ascetic Zen monk.

“Really?” said Mori Moritaki. “Is that what I look like? This is completely different, though, from the practice of Zen. I’m awfully far from overcoming the self. After all, my bitterness still comes up to about here.” With a smile, Mr. Moritaki gestured, putting his hand above his chest.

Even small acts lead to anti-nuclear solidarity

Yukio Yokohara, 54, director of the Hiroshima Congress Against A- and H-Bombs, has never missed a sit-in at the cenotaph since that protest of July 20, 1973, staged in response to a French nuclear test. The sit-in that took place on June 16, 1995 to protest France’s decision to resume its nuclear testing marked his 486th protest.

“When I open the newspaper, I first look for an article about a nuclear test,” Mr. Yokohara said. “Unfortunately, this has become a part of my life.”

Mr. Yokohara is originally from Tottori Prefecture. He came to be engaged in the peace movement through the union activities of the current All NTT Workers Union of Japan. He caught wind of a sit-in at a time when, somewhere in the back of his mind, he was feeling frustrated with the peace movement’s idealism. “I felt energy surging up through me from the stone pavement,” he recalled. “I had the feeling that I had finally found a campaign where I could break a sweat.”

One day, around the time Mr. Yokohara first joined the sit-ins, a visitor from abroad gazed fixedly at him. When Mr. Yokohara spoke to him, the man said firmly that he was opposed to nuclear weapons, too, and that his uncle’s decision was wrong. That man turned out to be the nephew of the late Harry Truman, the U.S. president who had ordered the A-bomb attacks. “To be honest, there was a time when I didn’t feel so positively about the sit-in protests,” Mr. Yokohara said. “But his words made me realize keenly that even a small act can create a common bond between people.”

Letters of encouragement have come as well. Elementary school students have taped donations of 100 yen coins to their letters. An anonymous telegram arrived, in care of “Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park,” that read simply: “Thank you.” Mr. Yokohara remarked, “Just a handful of people are sitting in protest, but actually, thoughtful people all over the world are sitting together with us.”

Sitting to protest a nuclear test by his homeland

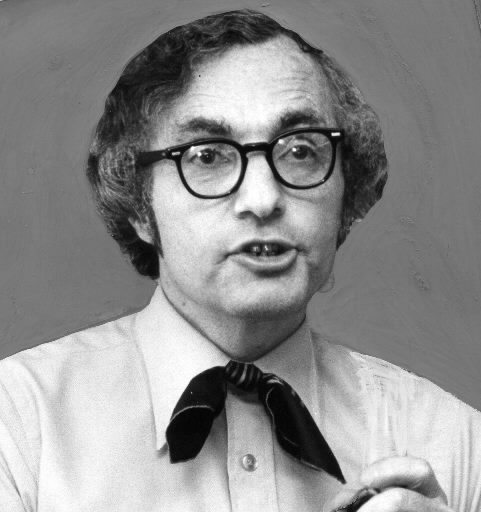

In May 1975, Robert Lifton, 69, an American psychiatrist who had researched the deep trauma suffered by A-bomb survivors and authored the book “Death in Life,” published in 1968, learned of a U.S. nuclear test while paying a visit to Hiroshima. He was in the city to take part in the production of a documentary film on the atomic bombing, and he sat in front of the cenotaph with A-bomb survivors and others.

Dr. Lifton sat alongside the late Ichiro Moritaki for an hour, explaining that he joined the protest because the nuclear test had been conducted by his own nation. After returning to the United States, he published an article entitled “Carriers of the Nuclear Disease” in The New York Times. In this piece, Dr. Lifton pursued the significance of the sit-in protests from the perspective of a psychologist.

“And indeed, even in Hiroshima where the professor is widely admired, many shake their heads sadly at the seeming futility of the act.

“Yet I take Moritaki’s sitting to be a dignified but profound reminder of the threat posed by our weaponry to our life as a human group, a reminder whose significance and potential power derives precisely from the place he sits, the experience he represents.

“It is sometimes said of Hiroshima survivors, and of the Japanese in general, that they suffer from a ‘nuclear allergy.’ The term correctly conveys the idea of sensitivity, but implies that this sensitivity is something of an overreaction if not a disease. Professor Moritaki gently informs us, however, that it is the rest of us, in our nuclear insensitivity, who are reacting inappropriately, and carrying the nuclear disease.

“Part of the disease is a peculiar madness lurking beneath the logic of international negotiations...”

The significance of the sit-in protests, backed by Dr. Lifton’s sharp, observant eye, received a positive reception. Mr. Moritaki and his associates were delighted: “The spiritual chain reaction of our sit-in protests has spilled over into the United States.”

Dignity seen in sit-in protests

Among those seated in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, an artist was silently sweeping a paintbrush across a sheet of paper. His name was Makoto Yoshino, 62, a resident of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, and he drew more than 300 sketches of A-bomb survivors and peace activists while joining in the sit-in protests himself.

Mr. Yoshino was a former art teacher at a junior high school. Motivated by his experience of the cruelty of war during his boyhood in the former Manchuria in northeastern China, he was also involved in peace education at his school. About 20 years ago, one student asked Mr. Yoshino, who was preaching the preciousness of peace: “Well, what are you doing for peace?” The question gave him a jolt.

In 1984, Mr. Yoshino left teaching, due to ill health and family concerns, and began taking active part in the sit-ins. Seating himself in the back row, he became deeply moved by the dignity of the A-bomb survivors and other citizens sitting there in silence. “Drawing the scene of these people staging the sit-in protests, preserving their efforts, is the action for peace that I can make as an artist,” he decided, finally finding an answer to the question his student had posed.

Mr. Yoshino’s sketches capture the backs or profiles of the participants. There are no sketches of full faces. Unless he puts himself within the circle of participants during these protests, his “heart aches because I feel I’ve become an outsider.” Based on the ideas he discovers through his sketches, Mr. Yoshino also pursues abstract paintings on this theme. In many of his works, the “X” shape of crossed legs appears. The artist has imbued the shape with his wish for nuclear abolition.

From June 1, Mr. Yoshino, along with an Argentine woman who is also a painter of anti-war images, opened a joint exhibition in Hiroshima entitled “Art Exhibition to Praise Hope.”

(Originally published on June 25, 1995)