History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 29, Article 1)

Mar. 20, 2013

Artistic Expression (Part 1)

by the “History of Hiroshima” reporting team

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

“When Hiroshima is forgotten, another Hiroshima will occur.” This is the thought in the minds of those who sensed the end of humankind in the horror of the atomic bombing. In their own ways, they are conveying the story of Hiroshima to the world.

Fifty years have now passed, and the atomic bombing is turning from “experience” to “history.” How should the reality of Hiroshima’s past be handed down to the next generation? In closing this special series, “History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995,” we will share, in two parts, the stories of those working to pass on the legacy of the A-bomb experience.

The first part will look at four people: writer Makoto Oda, actress Sayuri Yoshinaga, and singer Hiroko Ogi are all engaged in expressing their thoughts on Hiroshima through forms of literature and entertainment, while Koji Adachi, a young writer, is now taking up this task.

The accompanying chronological tables will show some of the series of articles on the atomic bombing that have appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun over the past 50 years.

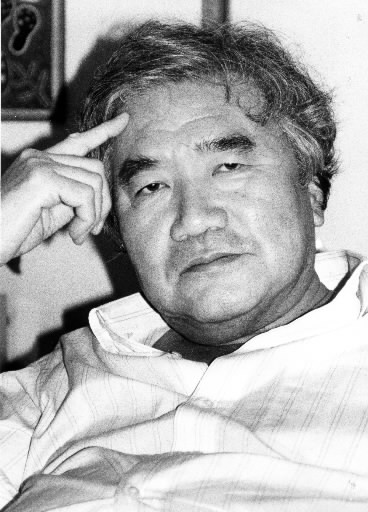

Writer Makoto Oda: Clarify who bears responsibility for the atomic bombings

There are still scars from the great earthquake [that struck Kobe in 1995] in the city of Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture. In a condominium on the fifth floor of a riverside building, Makoto Oda spoke volubly: “I predicted this. Japan’s always doing irresponsible things. The fire [which broke out after the quake] was the price paid for what’s been done in the 50 years since the war ended.” At 5:46 on the morning of January 17, his bookshelf—the glass still broken—toppled down toward his head.

“This is what saved me,” he said, turning his eyes to a copy machine beside his bed. The copy machine prevented the bookshelf from hitting him.

At the time, there was a sheet of paper in the machine. It was a document from the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), inquiring about producing a radio drama based on Mr. Oda’s book titled Hiroshima. “Isn’t that strange!” said the pacifist thinker to himself. For Mr. Oda, who is also a peace activist, the 50th year since the end of the war began with devastation wrought by the nation’s neglect, and a coincidence linked to Hiroshima.

Mr. Oda plans to be in London for the broadcast of the radio drama on August 6, and will provide an antinuclear message. On August 26, he will travel to the United States to take part in a recitation play, in which poems written by Jewish-American poet Rosenberg about the genocide committed by the Nazis and Mr. Oda’s Hiroshima will be recited, accompanied by music. “The 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima is a turning point for me, too,” Mr. Oda said.

When Japan’s defeat in the war came, Mr. Oda was a first-year student in junior high school. On August 14, Osaka suffered a massive air raid. A one-ton bomb exploded 200 meters from him, and he witnessed the charred bodies. What he would later call “meaningless deaths by unilateral slaughter” determined the course of his life. Based on his experience of the air raid, he wrote the novel Hiroshima.

“In the confusion after the war, I heard a rumor that American soldiers were also killed in the atomic bombing,” he explained. “So I did some research and found this was true. I thought I could write a novel, with the idea that the American soldiers were victims as well as perpetrators, and that this was Japan’s problem, too.”

Mr. Oda not only looked at the harm caused by the atomic bombing, but also regarded it as the culmination of all the discrimination and tragedy that had come before. The atomic bombs were developed at a test site from which Native Americans were forcibly removed, and were made with uranium that had been mined by slave labor in Africa. The B-29 bomber Enola Gay took off from Tinian Island, where Japanese soldiers died by suicide, committing “honorable deaths.” And under the flash of the bomb’s explosion were many Koreans and “special students” from Southeast Asia, who had been brought to Japan in the name of the establishing the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

“If we look at the atomic bombing from this wider perspective, it becomes clear what the tragedy was all about,” Mr. Oda said. “And it’s clear who bears responsibility: the American president and the Japanese emperor. The English version of my book is titled H, which stands for both Hiroshima and Hirohito, the emperor.”

Hiroshima won the Lotus Prize for Literature, the highest literary prize given in the third world. Mr. Oda, though, was simply happy for the fact that this prize is presented by nations, including countries in Asia, where people view the atomic bombings as a symbol of liberation from Japanese occupation. John Treat, a professor at the University of Washington [currently at Yale University], described Hiroshima as a bridge from “experience-based atomic bomb literature” to “nuclear literature” in his book Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb.

“I’m a Japanese literary figure, so I can’t be separated from the A-bomb experience,” Mr. Oda said. But experience alone isn’t enough to contend with the current situation surrounding nuclear arms. In Europe and America, what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is widely viewed not as nuclear war but as the closing of a conventional war. There’s a big gap in perception. For them, nuclear war is only part of an imaginary world. That explains arrogant nations like France. We need the mindset of renouncing nuclear war and universalizing Hiroshima.”

Mr. Oda says that Hiroshima should play the role of thinker, rather than teller. To achieve that end, what should be done? “Universalizing Hiroshima can be realized only when it’s predicated on responsibility for the war and the invasion of other nations. But for the past 50 years we’ve only been discussing the damage without holding anyone accountable for the war and invasion, without questioning who was responsible for the atomic bombings. And that was a blind spot which led to the reaction of the U.S. war veterans toward the Enola Gay exhibit at the Smithsonian Institute,” Mr. Oda said.

In war, victims can become perpetrators. Soldiers who are separated from their families and sent into battle have a hand in atrocities. This is the tragedy of war. And this is the reason Mr. Oda formed “Beheiren” (“Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam”).

“Up until that time, the peace movement in Japan was pursued from the standpoint of victims. That’s why it lost momentum,” Mr. Oda explained. “The issues of Hiroshima and the comfort women may seem to have nothing to do with one another, but at heart, they’re related. As this is a nation which is reluctant to hold itself accountable, even after 50 years, Asian people may well regard it as a nation which deserved the atomic bombings.”

On August 6, 50 high school students from Germany will visit Hiroshima. They are members of the Japan-Germany Peace Forum, which was established by Mr. Oda, for the most part, 10 years ago. “These are the only countries that understand that there is no such thing as a just war,” he said. “Hiroshima is a symbol of this idea. So Hiroshima has a responsibility to convey the suffering more forcefully.”

In tandem with Mr. Oda, during his time in London, the high school students will issue a statement to protest the nuclear weapons tests conducted by France. “Incidentally,” said Mr. Oda, “why doesn’t the mayor of Hiroshima fly to France and stage a sit-in in front of the Elysee Palace? It would certainly send an extraordinary message to the world.”

Koji Adachi, winner of award for best new writer from Gunzo Magazine: Message from the younger generation

I must now ask myself this question in calm contemplation: What experience of mine supports the peace I speak of? What choice am I making when I talk about Hiroshima?

I was born more than ten years after the time people began to embrace the idea that the postwar period was over. For someone like me, the motivation for talking about peace comes from within and becomes a choice. When talking about peace becomes an empty formality, however, we tend to forget that we ourselves have made this choice. It becomes an automatic behavior. For example, we brush our teeth or use our chopsticks without really being mindful of these activities, even though we ourselves are doing them.

Since such things are not innate habits, we must have made these choices at some point in our lives, but we have forgotten the fact of making them. The same thing occurs even in the realm of speaking about peace.

There is often criticism over the fact that Japanese students are not taught enough about the nation’s modern history in history classes up through high school. By comparison, a substantial proportion of German history textbooks cover the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis. This leads me to wonder about the current state of Japanese education and how schools are forced to focus on entrance examinations. Ironically, a paradox exists in which the postwar democracy now has difficulty teaching complex issues in a democratic fashion.

But the problem is not that students are not being taught. If schools are forced to take on the responsibility of teaching everything, they cannot perform well, and so students must be ready to teach themselves. When people say that they didn’t learn anything at school, this foul excuse comes from forgetting the fact that the individual must pay for his own ignorance.

What must be considered is the fact that, in the current system of education, students are not taught concrete details of the Fifteen Years War, while being provided only the concept of anti-war or peace, ideas which should be directly connected to facts.

Ideas cut off from historical facts will invariably become abstract and conceptual. Can we then feel their reality at all?

It is not only institutions for public education that are reluctant to deal with the history which is directly connected to our current era. In our homes, too, we have very few opportunities to learn about history. How much do we really know about the history of those who are closest to us, our fathers and mothers?

Despite the fact that we live together, aren’t we fearful of dealing with one another as fellow human beings? Aren’t we trying to avoid sharing our own history? If you don’t know the history and thoughts of your family members, you don’t really know what sort of people they are. In the final analysis, it also means that no one knows who you are, either.

This is a bizarre state of affairs. If things don’t change, we could end up with an abstraction of human beings in our systems of family, school, and institutions.

Personal experiences cannot help but become general historical facts as they are passed down from generation to generation. We may lament the fading memories, but for this very reason, we should continue to talk about them.

What is of paramount importance is the reality of the images conveyed through words. We must also realize that this is something we should choose to do. When we don’t have the personal experience to draw on, we have no choice but to use words to conjure the reality through imagination.

On the reverse of the title page of Hiroshima Noto (Hiroshima Notes), Kenzaburo Oe wrote: “In the pond of the Sentei [Asano Mansion], live carp were swimming among the dead bodies.” Though we have never seen carp swimming around the dead, these words, with the image of reality they convey, evoke strong feelings about the horror of the atomic bombing.

In Hiroshima and in other parts of the world where wars are still fought, there are many such words. We should not just repeat these words in empty formality, but must retain the real feelings within them and hand them down to posterity.

It is extremely difficult to talk about peace if we have not experienced war. But this difficulty will be the very force that supports the peace we speak of.

Profiles

Makoto Oda

Makoto Oda was born in Osaka Prefecture in 1932 and graduated from the University of Tokyo. Based on his experience in the United States as a Fulbright student, he wrote Nandemo Miteyaro (I Will See All That There Is), which became a bestseller. He played a leading role in forming “Betonamu ni Heiwa o Shimin Rengo” or “Beheiren” (“Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam”), which opposed the Vietnam War and Japanese assistance to the United States during this conflict.

Koji Adachi

Koji Adachi, 26, was born in Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture. After graduating from Kuremitsuta High School, he studied at the college of arts at Rikkyo University. In 1993, he won the award for best new writer from Gunzo Magazine for Kurai Mori-o Nukeru Tameno Hoho (Passing Through the Dark Woods). He lives in Narita, Chiba Prefecture.

(Originally published on August 6, 1995)