History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 30, Article 2)

Mar. 21, 2013

The news coverage of the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 2)

by Special reporting team for the 50th anniversary of the A-bombing

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

The past 50 years have been dominated by the pessimistic view that “peace comes only after a war.” Fortunately, there have been no wars on a global scale during that time. Perhaps this is because the experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki etched the brutality of nuclear weapons in people’s memories, and the “balance of terror” has stopped humankind on the brink of using those weapons. The duty of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is to continue to tell the world of the destruction that resulted from the A-bombings. If they can continue to tell their stories in a fresh way with renewed vigor, their experiences will remain vivid, and a new tragedy can be prevented. The Chugoku Shimbun’s coverage of the A-bombing over the past 50 years has been part of that effort. To conclude this series, “History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995,” we look back at what the newspaper has conveyed over the past 50 years.

Fifty years of A-bombing coverage: Looking toward the future

◆From the 1960s on

In the 1960s, the vigorous ban-the-bomb movement took on a more political tone, and faced an organizational split as the result of a rivalry between political parties. In its coverage, primarily editorials, the Chugoku Shimbun harshly criticized the fractured movement. On August 4, 1963, under a headline saying “Hiroshima is weeping,” the paper featured citizens’ voices venting their anger at the “haughty” peace movement. And in an editorial on March 20, 1964, the paper criticized the change in the ban-the-bomb movement from the perspective of the victims of Hiroshima’s A-bombing saying, “We can accept Hiroshima becoming a venue for the peace movement, but making it a venue for political party propaganda is an inexcusable insult to the more than 100,000 voiceless people in attendance.”

Meanwhile, the paper’s coverage turned to “hidden atomic bomb survivors” besides those in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The 11-part series titled “The Atomic Bomb Survivors of Okinawa,” published in 1964, is one example. A reporter went to Okinawa, which was then under the control of the U.S. military, on the pretext of covering sports and then interviewed atomic bomb survivors living there. The Chugoku Shimbun gradually expanded the scope of its A-bombing coverage. A reporter accompanied Barbara Reynolds and other participants in her World Peace Pilgrimage, and in 1964 a 39-part series of articles titled “Hiroshima in the World: Traveling with the Peace Pilgrimage” was published.

Historical record

In 1965, the 20th anniversary of the A-bombing, the Chugoku Shimbun’s coverage of the bombing reached a peak. Centered on the three major themes of “destruction,” “peace” and “inheritance,” thirty full-page feature articles were published. These features, which were groundbreaking for the time, were titled “Conveying a message to the world,” “Lineage of the flames,” and “Record of Hiroshima.” A series in the paper’s evening edition entitled “Out of the ashes: the inside story of the rebuilding of Hiroshima” focused on “reconstruction.”

Behind these articles lay the harsh reality faced by the atomic bomb survivors. Beset by poverty and illness, they were also marginalized and experienced discrimination in marriage and employment. At the same time, 20 years had passed since the A-bombing and reporters began to look at its effects more objectively and developed an awareness of the need to create a historical record.

In 1968 the Chugoku Shimbun ran a series on atomic bomb survivors in Okinawa followed by a three-part series titled “Forgotten atomic bomb survivors: a plea from South Korea.” This was the paper’s first reporting on atomic bomb survivors in South Korea, whose actual number was not known at the time. The paper has continued to cover the issue of A-bomb survivors in South Korea over the years.

Effort to enact Survivors Relief Law

Amid these circumstances, during Japan’s high economic growth period from the latter half of the 1960s to the 1970s, the issues of the A-bombing and the atomic bomb survivors became less visible because the suffering of the atomic bomb survivors became more difficult to portray in a tangible way as the living standards of the overall population rose.

The emphasis gradually shifted from Hiroshima’s experience of the atomic bombing to Hiroshima as a symbol, and “peace coverage,” which focused on the abolition of nuclear weapons, peace and the issue of disarmament, was added to the paper’s reporting on the atomic bomb survivors, which was referred to as its “primary coverage.” The issue of nuclear power plants also became a more immediate problem, but as the paper’s coverage expanded to include a wider range of issues, it tended to be less in-depth.

The issues of elderly survivors and the children of survivors became the focus of the paper’s “atomic bomb survivor coverage.” To avoid falling into a rut, reporting began to involve efforts such as digging up materials, making the reports more relevant to the times and uncovering issues related to the atomic bomb survivors through investigative reporting on hospitals and nursing homes that specialized in their treatment. Around this time the paper also published special features that pointed out the limitations of the two atomic bomb-related laws (the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law and the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law) and called for an Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.

At the time of the nuclear arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, the focus of the paper’s “peace coverage” was a series on peace education to pass on the symbolism of Hiroshima, while its “United Nations coverage” began with coverage of the visit by Takeshi Araki, former mayor of Hiroshima, and others to the U.N. in 1976 and the first U.N. Special Session on Disarmament in 1978.

But while this peace and United Nations coverage contributed to the globalization of Hiroshima, it also gave rise to the so-called “United Nations illusion” whereby absolute trust was placed in the U.N. and coverage tended to give precedence to the ideology of Hiroshima and lack a sense of reality. For this reason, series that focused on passing on accounts of the A-bombing experience were published, and from then on “peace coverage” and “primary coverage” were linked in the paper’s coverage of the Hiroshima.

Broader perspective includes nuclear accidents

In the first half of the 1980s, coverage of Hiroshima as a symbol of the peace movement became more common against the background of the growing anti-nuclear movement in Europe. With the disasters at the nuclear power plants on Three Mile Island in the U.S. in 1979 and in Chernobyl in the Soviet Union in 1986, the Chugoku Shimbun took up the issue of those who were exposed to radiation as the result of nuclear accidents and nuclear tests and linked them to Hiroshima in a special series of articles. Articles looking at these victims from the perspective of Hiroshima also appeared in the pages of the paper, and a new type of “hibakusha coverage” was added to the paper’s “primary coverage” and “peace coverage.”

Around this time reporters from local newspapers in the U.S. were invited to Hiroshima and Nagasaki so they could write about what they saw there. This program, a new initiative by the paper, was undertaken for about 10 years. More recently it was felt that the paper should take a look at Hiroshima not only as a victim but also as an aggressor, and articles examined Hiroshima as it embodied Japan’s wartime militarism and policy of aggression. The paper also tirelessly pursued its primary coverage of the atomic bomb survivors. Coverage of both of these issues was marked by long series that ran for six months to a year.

Fifty years have passed since the atomic bombing. The Chugoku Shimbun’s coverage of Hiroshima has continued unbroken. Its goals were the reconstruction of the destroyed city, commemoration of those who died, relief for the suffering atomic bomb survivors, and the realization of a pledge that nuclear weapons never be used again and that no more lives be lost to them.

But the coverage over the past 50 years was quite often stale or perfunctory, was merely “reporting for the sake of reporting” or was limited to the summer. At the same time, some over-earnest coverage offended the atomic bomb survivors in its eagerness to pursue tragedy.

Expressions such as “the heart of Hiroshima,” “the reality of the atomic bombing,” “the hearts and minds of the atomic bomb survivors” and “the abolition of nuclear weapons” became sullied and lost their impact. Illusions were created as well: the United Nations illusion, the illusion of A-bomb survivors as saints, and the illusion of Hiroshima as a “holy city.”

“I learned the heart of Hiroshima by being exposed to its reality.” Describing these stereotypical illusions using clichéd expressions ultimately means destroying one’s own reporting. Fifty years after the A-bombing it is increasingly important to take an approach to reporting that involves realizing one’s goal while staying grounded in reality and without leaning on illusions.

What I would like the Chugoku Shimbun to do

Participate in anti-nuclear movement, create momentum

by Kazunari Abe

I started subscribing to the Chugoku Shimbun in the mid-1960s for two main reasons. One was its extensive coverage of nuclear weapons-related issues. That was based on my need for information so I could play a small part in the ban-the-bomb movement. First of all, if I was going to keep up my activities, it was essential that I be frequently exposed to the reality of the atomic bombing. Opportunities to hear survivors talk about their experiences are limited, so the Chugoku Shimbun’s various reports on this were valuable to me. Secondly, learning about the movement, both in Japan and overseas, to abolish nuclear weapons was very encouraging. Thirdly, the paper’s unrivaled reporting, analysis and opinions on the circumstances surrounding nuclear-related issues were very important in determining how to advance the movement.

This year as well, through the histories of the hard lives of the atomic bomb survivors in the 50 years since the A-bombing, the Chugoku Shimbun has reminded us of the significance of the question asked by the co-pilot of the Enola Gay: “My God, what have we done?” And through this “History of Hiroshima” series, the paper has considered the profound implications of Hiroshima in the modern age.

But how thoroughly do the readers of the Chugoku Shimbun read its articles on nuclear-related subjects? In particular, how many young people read them? My fears may be completely groundless, but I’m a little concerned about this. Nevertheless, even if some people feel the Chugoku Shimbun is biased toward coverage of A-bomb-related issues, I feel the paper has played an invaluable role by instilling anti-nuclear-weapon sentiment in many of its readers. In order to ensure that memories of the A-bombing do not fade in the future, as time passes the horrors of the A-bombing must be conveyed in more vivid terms than ever. In connection with this, the stance of the Chugoku Shimbun’s future employees, who will be born over the years to come, will be called into question.

It seems safe to say that most people are opposed to nuclear weapons and desire a world without nuclear weapons, but there don’t seem to be many people involved in the anti-nuclear movement. Few people attended the special event marking the 50th anniversary of the A-bombing that was sponsored by the Hiroshima Prefecture Congress against A- and H-bombs. In the July 30 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun, Sakae Ito, president of the Hiroshima Prefecture Federation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations, was quoted as saying, “Is this acceptable?” Most people are against nuclear weapons but seem to have the idea that in reality eliminating them is nearly impossible. Looking at it that way, I would like to think that the path toward the elimination of nuclear weapons must be clearly spelled out along with what sort of action we should take. But what must we do toward that end?

While redoubling our efforts to convey the reality of the A-bombing to people in Japan and abroad, we must go beyond merely raising our voices against nuclear weapons and come up with a way to sway international politics in order to bring an end to the “nuclear age.”

I hope the Chugoku Shimbun will continue to provide coverage that closes in on these weighty issues and state its positions on them. I believe that doing this will not only dispel mindless criticism that “the Chugoku Shimbun is just trifling with the A-bombing” but will also serve as a motivating factor for quite a few people to get involved in the movement. I hope as many people as possible will take the initiative to act and that they will work together in Japan as well as on a global level to continue their activities. If they do so, the prospects for the abolition of nuclear weapons will brighten and the Chugoku Shimbun will be able to convey that message with confidence.

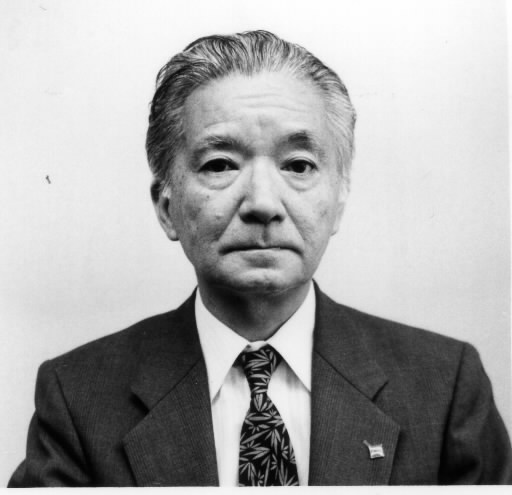

Kazunari Abe

Has been involved in the ban-the-bomb movement since his days an associate professor at Yamaguchi University. Served as chairman of the board of both the Yamaguchi Prefecture Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs and Yuda-en, a prefectural social welfare center for A-bomb survivors. President of the University of East Asia. Professor emeritus at Yamaguchi University. Sixty-eight years old.

Coverage of the A-bombing: Comments from former reporters

Reporters’ views of history called into question

Minoru Omuta, 64, resident of Higashi Ward, Hiroshima

The Chugoku Shimbun’s reporters have been on the ground digging up stories on the actual situation of the atomic bomb survivors. This is a major achievement in the history of Japanese newspaper reporting. On the other hand, the paper’s coverage of the A-bombing has been overly emotional in some respects. The problem is what happens after the 50th anniversary of the A-bombing. The Chugoku Shimbun must go on conveying the reality of the A-bombing and continue to pursue the abolition of nuclear weapons and peace. But it must do so without being content to make a perfunctory call for nuclear abolition and address other issues facing us such as poverty and the environment. In this day and age we must think of dealing with these issues one by one as one way to bring us closer to a solution to the problem of nuclear weapons. What is most important from here on out is for individual reporters to have a distinct world view and a view of history and to write based on that. People won’t be able to relate to the issue of peace with fuzzy reporting on the A-bombing. This is what will be required of the news media in the future. (Mr. Omuta retired in March 1992.)

Ongoing interest

Shigeru Kawada, 66, resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima

I based my reporting on this idea: What if the atomic bomb had been dropped on me? Everyone has the right to be treated fairly and live in peace. Infringing on that right is the height of arrogance. Maybe I was rebelling against that. I have met many atomic bomb survivors, and there is no doubt that their lives were turned upside down by the A-bombing. People say that the survivors should loudly proclaim their experiences to ensure that their stories are passed on, but most of the survivors have died without ever having spoken of their experiences. Is it right to speak out and wrong not to? Viewed only from the outside, Hiroshima cannot be seen, and viewed from the inside it cannot be seen in its entirety. It is a city that is hard to grasp. How will Hiroshima change once it passes the 50th anniversary of the A-bombing? Or how can it change? Some things must not change. Even though I’ve stopped writing news articles, I continue to take an interest in the A-bombing. I am not an atomic bomb survivor, but as long as I am a resident of Hiroshima let me have my say. That’s how I feel. (Mr. Kawada retired in September 1987.)

Reporters too must pass on their experiences

Yoshio Asano, 64, resident of Minami Ward, Hiroshima

Those who should have died survived. Three hundred first-year students at Hiroshima Second Middle School (now Hiroshima Kanon High School) died in the atomic bombing instead of those of us in the second year. I still feel guilty about that. That day the first-year students went to the area that is now Peace Memorial Park to dismantle buildings. All of them were killed. The day before, August 5, we second-year students had been in just about the same place. The way the work happened to be assigned was the difference between life and death. After I became a newspaper reporter, instead of overemphasizing the horrors of the A-bombing I tried to convey what happened to ordinary people who experienced the A-bombing and the tremendous gap between them and those who did not have that experience. When I listen to the stories of atomic bomb survivors, memories of that time come back to me: the smell of pus, the feel of blood, the stench of death. People who can recount those experiences are beginning to disappear. I think reporters must now make an organized effort to pass on their experiences of the atomic bombing as well. (Mr. Asano retired in December 1993.)

(Originally published on August 13, 1995)