Fukushima and Hiroshima, Part 4 [Special]

Aug. 3, 2011

Medical care for atomic bomb survivors

66 years of experience

by the “Fukushima and Hiroshima” reporting team

The 66th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, is approaching. Over the past 66 years there has been ongoing research in Hiroshima into the effects of radiation on the human body. Grounded in the sacrifices of the victims of the bombing, this experience is now being put to use on behalf of those who fear the possible effects of the accident at the No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant in Fukushima.

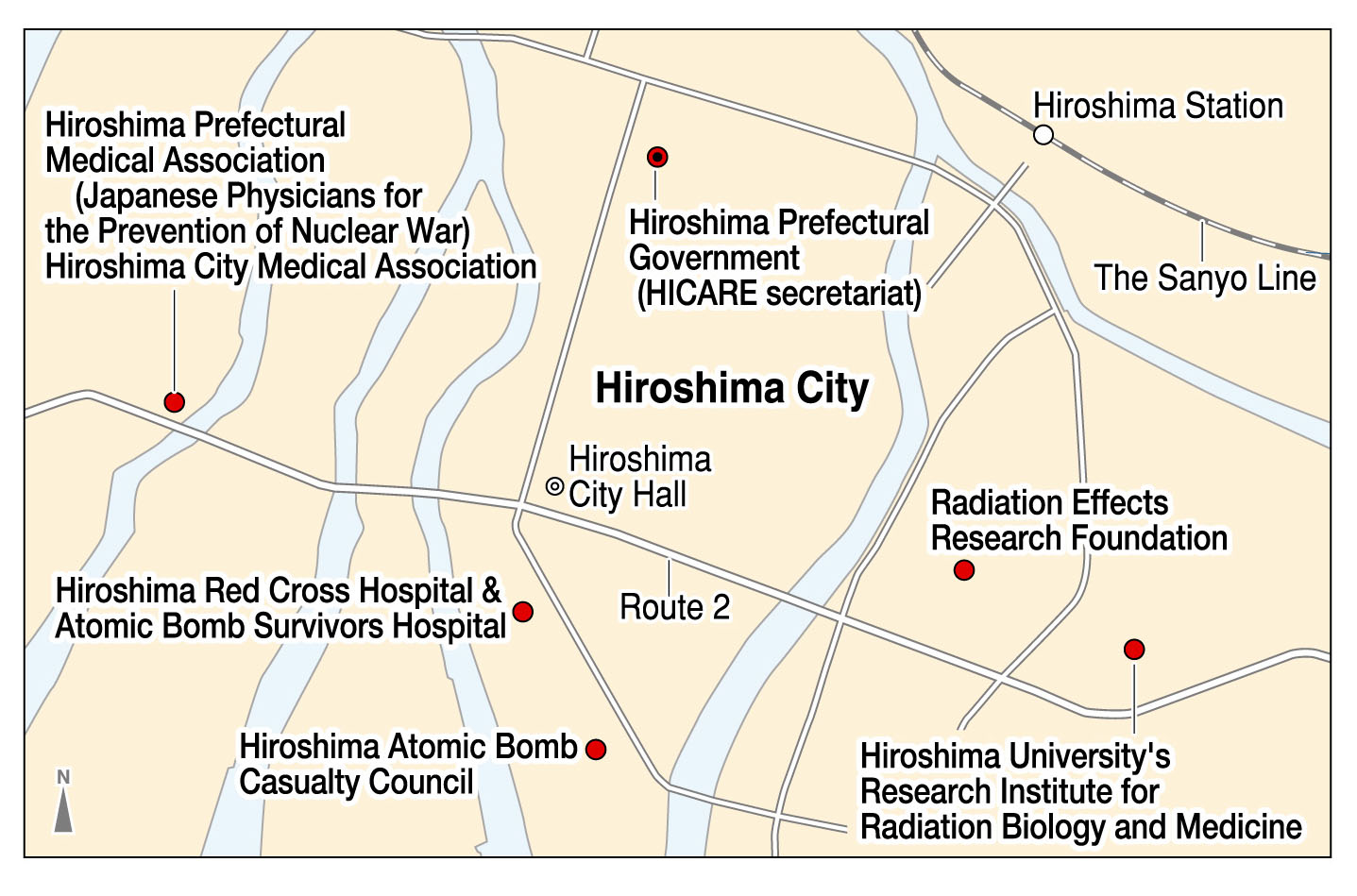

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Research Institute for Nuclear Medicine and Biology (now the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine) at Hiroshima University. That same year the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council opened the Atomic Bomb Survivor Welfare Center to provide health care and other support services to atomic bomb survivors. The Radiation Effects Research Foundation continues to conduct follow-up studies on approximately 120,000 people. This article looks back over the history of the medical care that has been provided to atomic bomb survivors, which now holds promise for the people of Fukushima.

Expectations in both clinical and research areas

Shelves filled with the medical charts of atomic bomb survivors occupy one room of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Council’s Health Management and Promotion Center. “These are the records of only 80,000 people. The charts of another 100,000 who have already died are in another room,” said the employee in charge of the records. Each record, from the yellowed charts of the 1950s to the most recent records, is filed under a control number and represents the chart of someone who has undergone regular health checks.

The predecessor of the council, the Hiroshima Municipal Atomic Bomb Casualty Medical Treatment Council, was a voluntary organization established by the local medical association and the city in 1953 in an effort to provide medical care to the atomic bomb survivors in an organized manner. The leaders of the group were physicians in private practice who were struggling to treat the keloid scars of atomic bomb survivors. The effectuation of the peace treaty ending the war with Japan, which took effect the year before, brought an end to the control of information by the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces, and the effort to provide relief to the atomic bomb survivors quickly gained momentum.

In 1956 the Hiroshima Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital was established within the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. The following year the hopes of the atomic bomb survivors were realized when the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law took effect. About ten years after the atomic bombing, a system had finally been established to provide medical treatment and health care services to the survivors at the responsibility of the government.

Sadamu Ishida, 85, worked at the Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital from the year after it opened until 1982 and served as head of the internal medicine department. Under the late Fumio Shigeto, director of the hospital, who was fondly referred to as “father” by atomic bomb survivors, Ishida treated outpatients as well as inpatients, who filled the hospital’s wards.

“At the time, the most common condition was acute leukemia,” he said. “Later cases of lung cancer and other diseases increased. Every day I just fumbled along. I felt despair on countless occasions because I couldn’t save the lives of my patients.”

In the 1960s Dr. Ishida traveled to Hokkaido, Toyama and other areas at the request of local governments to examine atomic bomb survivors living there. He also went to Okinawa before it was returned to Japan by the U.S. and joined a group that traveled to South Korea, which relief efforts had still not reached even into the 1970s. He put the belief that “atomic bomb survivors are atomic bomb survivors no matter where they are” into practice from a medical standpoint.

The medical treatment of atomic bomb survivors began with the all-out relief effort that got underway just after the dropping of the bomb on August 6, 1945. Today support is provided at multiple levels by primary care physicians, atomic bomb survivor organizations, social workers and the government. Meanwhile research institutions such as the Radiation Effects Research Foundation and Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine have conducted extensive research into the effects of radiation on the human body.

Hiroshima’s experience in both the clinical and research areas was put to good use in providing medical assistance following the accident at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union and at the time of the criticality accident in Tokaimura, Ibaraki Prefecture, in 1999. The people of Fukushima have high hopes for the use of Hiroshima’s experience in connection with the accident at the No. 1 nuclear power plant there.

At the same time, it is a fact that even now there are problems with medical care.

Under the A-bomb disease certification system, survivors can receive a special medical allowance if an illness is recognized as having been caused by the atomic bombing. But a spate of lawsuits has been filed by people who believe their applications were wrongly rejected. In a class action suit filed in 2003, internal exposure to radiation, which has been a focus of concern in Fukushima, has been a point of contention between the government and atomic bomb survivors because much about the effects of exposure to low doses of radiation and internal radiation has yet to be explained.

Meanwhile people who were exposed to black rain containing radioactive materials in areas outside the area designated by the government are growing old without being recognized as atomic bomb survivors. Measures to redress the gap between survivors living in Japan and those living overseas are moving forward, but, unlike for those residing in Japan, there is still an upper limit on the amount of medical care subsidies those living overseas can receive.

Over the years Hiroshima has learned by trial and error. Now it is Hiroshima’s responsibility to do what it can for Fukushima to ensure that it will not go down the same road.

Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine: Health studies conducted using advanced science

On July 2 Kenji Kamiya, 60, director of Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, spoke to about 80 parents and others in the gymnasium of Kakeda Elementary School in the City of Date, Fukushima Prefecture. “I would like to allay your fears by conveying the knowledge Hiroshima has acquired through its experience,” he said.

After the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, Kamiya was asked to serve as vice president of Fukushima Medical University so that he could advise the prefecture on the management of health risks associated with radiation. He spends more than half of every week in Fukushima and has been busy giving lectures to parents and setting up a medical system at the university. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, and Kamiya is serving as the “face” of Hiroshima’s medical care.

The people of Fukushima are hopeful that the institute will be able to assist them because it is one of the few centers in the world that conducts research into the hazards of radiation. The institute was originally established in 1961 in order to scientifically clarify the harmful effects of radiation on atomic bomb survivors, and Dr. Kamiya specializes in medical care for radiation damage. After graduating from Hiroshima University’s Faculty of Medicine in 1977, he worked as a research assistant and later as a professor at the institute. He conducted research into the mechanism by which cancer develops and in 2001 was named the institute’s 13th director.

The following year he embarked on a reorganization of the institute focusing on genome science. He said his aim was to identify the mechanism by which cancer and leukemia occur at the genetic level, which could lead to the development of the latest treatments and preventive measures.

With a staff of approximately 45 researchers, the institute conducts research in a variety of fields. One field that has attracted attention is the institute’s analysis of the area in which black rain fell just after the dropping of the atomic bomb. This know-how is being put to use in a survey of the soil in Fukushima, which was contaminated over a wide area as a result of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

There are as yet no prospects for bringing the situation at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima to a close, and the residents of the surrounding area have been exposed to low doses of radiation for an unprecedentedly long time. “The institute’s advanced scientific research, which is its strength, is essential for shedding light on the impact on the health of the residents of Fukushima Prefecture,” Dr. Kamiya said, expressing his intention to make extensive use of the institute’s 50 years of experience.

An interview with Kozo Sanada, president of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council

Offering reassurance to Fukushima

How can Hiroshima’s experiences providing medical care for survivors of the atomic bombing be put to use in Fukushima? The Chugoku Shimbun talked to Kozo Sanada, 80, president of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council, about this issue and the history of the care that has been provided in Hiroshima. The following are excerpts from that interview.

What is the significance of doctors from Hiroshima going to Fukushima?

Doctors from Hiroshima were dispatched to Fukushima immediately after the accident at the No. 1 nuclear power plant. Radiation can not be seen or smelled. Without specialized knowledge even medical personnel feel anxious.

In addition to their experience in caring for survivors of the atomic bombing, the experts from Hiroshima have conducted surveys and research into the harmful effects of radiation after the [1986] accident at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl and in other incidents all over the world. Because of this experience they can accurately assess doses of radiation in Fukushima and offer advice. The people in Fukushima seem to feel reassured by their presence.

What role did the doctors of Hiroshima play right after the dropping of the atomic bomb?

Just after the war the medical care of atomic bomb survivors in Hiroshima went through a difficult period. The United States, which dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and then occupied Japan, repeatedly said that there was no need to be concerned about the radiation from the atomic bombing, and the survivors of the bombing were practically ignored. Tomin Harada and Gensaku Oho, two doctors in private practice, doubted this and were angry about it. They stood by the survivors and conducted extensive research.

Their zeal motivated local politicians and the mayor, which led to the founding of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council in 1953 and the passage of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law in 1957. The Daigo Fukuryu Maru was exposed to radioactive fallout as the result of a [1954] test by the U.S. of a hydrogen bomb on Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific, and people outside Hiroshima and Nagasaki began to sense the frightfulness of radiation, which was also a factor.

In what ways have you been involved with atomic bomb survivors?

After graduating from Hiroshima Medical College [now the Hiroshima University Faculty of Medicine] in 1955, I examined several thousand atomic bomb survivors as a surgeon employed by hospitals and in private practice. When I examined people who had shards of glass embedded in their bodies as a result of the bomb’s blast and women whose skin was overgrown with keloid scars, I was reminded once again of the cruelty of the effects of the atomic bombing. In addition to providing treatment I listened carefully to the experiences of the survivors and tried to understand their feelings.

Local doctors have been active not only in Hiroshima. They have also focused on atomic bomb survivors living overseas and have examined survivors living on the Korean peninsula, in the U.S. and in other areas. The accident at the nuclear plant in Chernobyl led to the establishment of the Hiroshima International Council for Health Care of the Radiation-exposed in 1991, and that organization is still bringing interns from overseas to Hiroshima and sending doctors overseas.

What should the government do for the people of Fukushima?

The methods by which support has been provided to the atomic bomb survivors will serve as a useful reference. The government should create a system like that of the health certificates for the atomic bomb survivors. Along with free regular check-ups, if they develop some sort of symptoms the government must provide them with a health care allowance and other benefits. An organization like the Atomic Bomb Casualty Council that brings together patients and doctors is also necessary.

And the government must not forget to follow up on those who move away from Fukushima when they are transferred or change jobs or for other reasons. Over the years Hiroshima has emphasized that atomic bomb survivors are atomic bomb survivors no matter where they are. The government must create a mechanism that will allow them to get the benefits of free health examinations and other care no matter where they move, including overseas.

Kozo Sanada

Born in Mukaihara-cho (now part of the City of Akitakata) in Hiroshima Prefecture in 1931. Surgeon. Opened his own clinic in Hiroshima in 1966. After serving as president of the Hiroshima City Medical Association was named president of the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association in 1998. During his six-year term, also served as president of the Hiroshima branch of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. Assumed his current post in 2005.

Principal doctors who provided care in Hiroshima

Fumio Shigeto

Was exposed to the atomic bomb in front of Hiroshima Station, 1.2 km from the hypocenter, just after being appointed assistant director of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. Played an active role in the establishment of the Hiroshima Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital and in 1956 became its first director. Until his retirement, examined more than 100,000 atomic bomb survivors over the course of about 30 years. Endeared himself to the survivors, who referred to him fondly as “father.” Died in 1982 at the age of 79.

Michihiko Hachiya

Exposed to the atomic bomb at his home 1.4 km from the hypocenter. While still covered in blood, hurried to the Hiroshima Communications Hospital, where he served as director, and supervised younger doctors in providing treatment for victims of the bombing. His book “Hiroshima Diary,” which was published in 1955, described the cruelty of the bombing from his perspective as a doctor. It was translated into numerous languages and published in countries around the world. Died in 1980 at the age of 76.

Tomin Harada

Was serving as a military doctor at the end of the war. After returning to Hiroshima in 1946, began providing medical care to atomic bomb survivors. Treated and researched keloid scars and other effects of the atomic bombing. Founded the World Friendship Center, an institution for the promotion of exchanges on international peace, in Hiroshima in 1965 and served as its chairperson. Died in 1999 at the age of 87.

Yoshimasa Matsusaka

One of the prime movers behind the establishment of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council and served as its vice president. Was exposed to the atomic bomb at his home 1.2 km from the hypocenter. Worked hard to provide medical treatment and aid to victims despite his own injuries. After passage of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law was appointed a member of the Council on Medical Care for the Atomic Bomb Exposed established by the former Ministry of Health and Welfare to review applications for certification as a sufferer of A-bomb sickness. Consistently spoke out from his perspective as an atomic bomb survivor. Died in 1979 at the age of 91.

(Originally published on July 26, 2011)