Fukushima and Hiroshima: Imprint of nuclear power plant accident remains deep

Sep. 27, 2011

Six months after the disaster: 50 residents of the Hamadori region today

by Seiji Shitakubo, Yoko Yamamoto and Yo Kono, Staff Writers

Six months have passed since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. More than 100,000 people have been displaced from their homes and are still living as evacuees. The 50 residents in our survey, who were living in eastern Fukushima Prefecture, which is known as Hamadori, are no different. The majority of them are unable to return to their homes. The nuclear power plant continues to emit radioactive materials, and the soil and sea remain contaminated. What has the government has done and what do the residents expect of Hiroshima? We recently interviewed the 50 residents of Hamadori about their lives now.

Health

Concern about exposure to radiation can’t be dispelled: Urgent need for testing

“I am a ‘hibakusha.’ I don’t think I’ll be able to get that out of my mind as long as I live,” said Chihiro Suzuki, 18, who lived in Namie, 9 km from the nuclear power plant. In mid-August she underwent a thorough test for internal exposure to radiation using a whole body counter.

The test result came back “below measurable limits,” but Ms. Suzuki said she can’t forget what the technician who conducted the test said: “This does not mean your exposure was zero.” Ms. Suzuki, who hopes to have children in the future, asked the technician about the possibility of genetic effects. The response was, “Hmm, I don’t know about that.” Ms. Suzuki is still concerned.

■ □

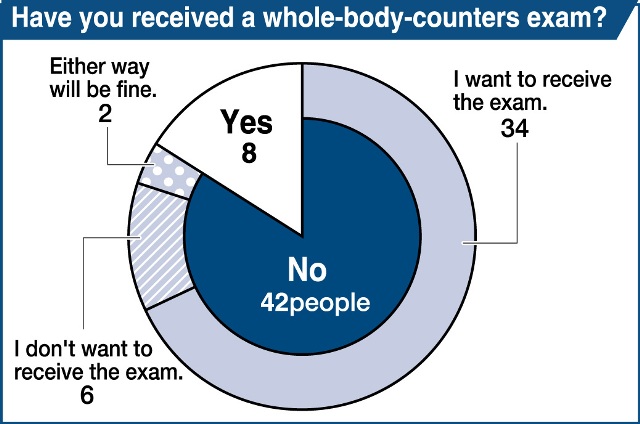

In these most recent interviews, eight of the 50 Hamadori residents said they had already been tested for internal exposure to radiation. All of them were told their exposure was “below measurable limits.” Four who received that result said they were relieved, while the other four said they could not completely dispel their anxiety about possible long-term effects.

Of the 42 residents who have not undergone the test, 34 said they would like to do so. But there is a lack of testing equipment, and the majority of them do not even know when they will be able to be examined with the whole body counter.

While they wait, radioactive materials will be flushed out of the body in the urine, and it will become difficult to determine the amount of the residents’ internal exposure to radiation. “The government should make arrangements for testing everyone as soon as possible,” said Shunji Sekine, 69, a doctor from Namie.

The parents of small children also feel uneasy. Tomoko Shineha, 27, who has a 2-year-old daughter, is a resident of Minami Soma, about 22 km from the nuclear power plant. She continued to live there for nearly 10 days after the accident. “It may be only a very tiny amount, but it’s a fact that my daughter has been exposed to radiation. When I think about her future…,” she said tearfully.

The occurrence of cancer or other health problems related to exposure to radiation several years or decades from now accounts for a large part of the residents’ concern. Akemi Obata, 44, a resident of Futaba, evacuated the day after the accident and is now living in Saitama Prefecture with her son, who is in the first grade. She said she has no intention of returning to Fukushima in the foreseeable future. “I wouldn’t want to have any regrets as a mother if my son were to get some sort of illness,” she said.

□ ■

Are Hiroshima’s experiences and knowledge proving useful? Hachiro Sato, 59, of Iitate said he relied on Osamu Saito, 64, a doctor at Watari Hospital in Fukushima City. Dr. Saito has examined atomic bomb survivors in Hiroshima for more than 30 years. “When anything comes up, I see him right away,” said Mr. Sato. “When he tells me not to worry, I feel relieved.”

Kenta Sato, 29, also of Iitate, also said he relies on Hiroshima’s experience. “I would like the records of individuals’ exposure to radiation to be preserved,” he said. He has prepared notebooks for people to make detailed records of their activities after the accident and plans to distribute them to residents in the near future. When embarking on this project, he consulted with the Hiroshima Prefecture Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hidankyo) (chaired by Kazushi Kaneko). Hidankyo advised him that records of activities would carry more weight if they had witnesses and that if pre-existing medical conditions were included in the entries any connection with exposure to radiation would clearly emerge.

“If I don’t take action, the situation won’t change,” Mr. Sato said. The government was also slow to take relief measures at the time of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Life as evacuees

Will we be able to return home?: Interest in Hiroshima’s recovery process

Temporary housing where approximately 400 evacuees from Iitate are now living was built in one area of an industrial complex on the outskirts of Fukushima City in late July. Mikiko Sato, 60, serves as manager of the housing complex. Ms. Sato, who is chair of Iitate’s women’s society, raised livestock with her husband before they evacuated.

Every day as noon approaches Ms. Sato walks around the housing complex. When she finds apartments with the curtains drawn, she knocks on the window. “I check to make sure elderly residents are all right,” she said. The other day she passed out flats of flowers she had received from a friend to every household. “Many of the residents were farmers before the accident, so I imagine they miss tilling the soil,” she said.

■ □

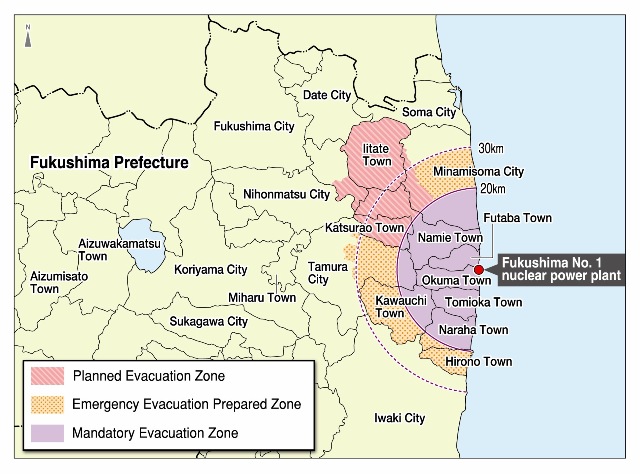

Iitate, which is located about 40 km from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, became a radioactive hot spot. All of the village’s more than 6,000 residents were forced to evacuate. Of these, approximately 1,200 are now living in temporary housing at nine locations.

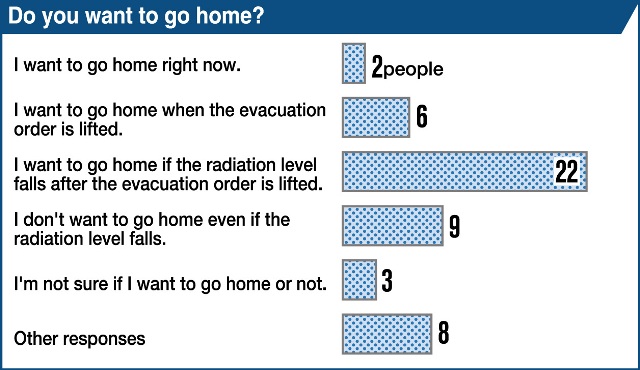

Forty-six of the 50 Hamadori residents in our survey continue to live as evacuees. One person has lived in as many as 12 different places since the disaster. Some have relocated as far away as Yamagata and Kanagawa prefectures. The municipal functions of Futaba have been shifted to Kazo in Saitama Prefecture, and three of the Hamadori residents are now living there. One of them, Tomiko Nakamura, 60, said, “I’m mentally exhausted.” Other residents in the area said they were under a lot of stress.

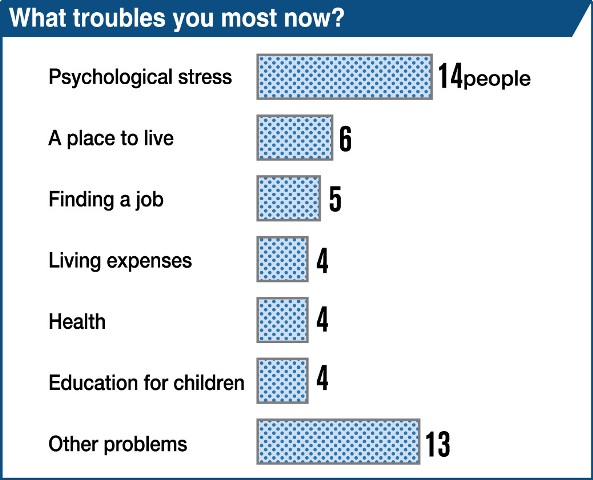

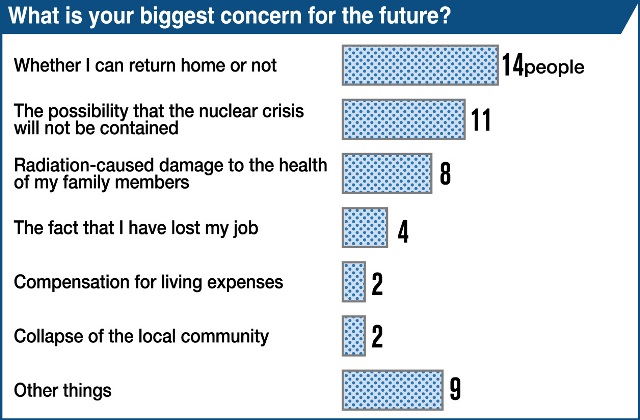

The 50 Hamadori residents were asked what their greatest concern for the future was. The most common answer, at 14 respondents, was whether or not they would be able to return to their homes. The next most common, at 11 respondents, was the possibility that the accident at the nuclear power plant might not be brought to a conclusion. Shiro Yamada, 72, of Namie gave this question a lot of thought.

“I want to go back to my hometown, but realistically speaking I don’t think that will be possible for quite a while.”

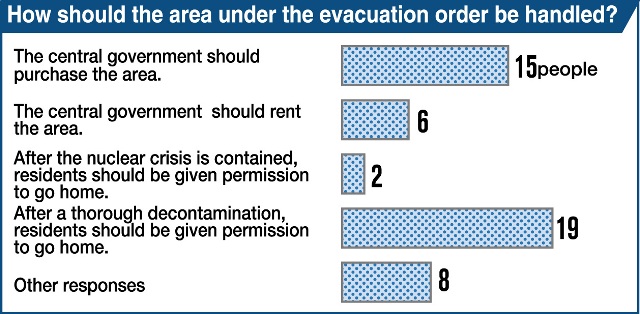

Mr. Yamada is head of the agricultural mutual relief association for the Futaba region. He looks at issues from the perspective of a farmer. “The government says they will decontaminate the soil, but they can’t decontaminate entire mountains. When it rains the contamination will spread,” he said. During the interviews others were pessimistic and wondered whether there was any future for towns to which children do not return.

The fact that the future is unclear although six months have passed has led to dissatisfaction with the government. In late August a representative of Namie’s town council met with residents who have relocated to Fukushima City. Koji Suzuki, 58 pressed the representative to take a tougher stance when seeking compensation in negotiations with the government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company, operator of the nuclear power plant.

Mr. Suzuki’s home was washed away by the tsunami and he has no idea when he will be able to resume commercial fishing. “The influence of government on both the national and regional levels is being called into question,” he said. In response to this observation, the other participants in the meeting applauded.

□ ■

At a press conference on September 2, the day of his appointment, Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda said, “There will be no rebirth of Japan without the rebirth of Fukushima.” But while touring the disaster area Yoshio Hachiro, minister of Economy, Trade and Industry, made comments to the press corps such as, “I’ll give you some radiation.” On September 10, the day before the six-month anniversary of the disaster, Mr. Hachiro resigned to accept responsibility for his remarks. The residents of the disaster area were angry and disappointed.

The future is uncertain, and many difficulties are expected to be encountered on the road to recovery. Some among the 50 Hamadori residents wonder how it was for Hiroshima. Yoshiko Suganami, 40, is a resident of Okuma, where the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant is located. “I would like to hear about the medical treatment for radiation-related illnesses and the methods used to survey doses of radiation in Hiroshima,” she said. After six months, these sorts of concerns have become more familiar to the residents.

1. Residence at time of accident (current situation)

2. Occupation/title

3. Comment

Keisuki Oka, 31

1. Minamisoma (living at home)

2. Firefighter

3. His parents run a dairy farm. As a result of the accident they had to sell 46 cows. Since June they have bought eight cows to be used for breeding. They expect it will be two years before they can resume selling milk. “I want the government to hurry up and start paying compensation,” he said.

Ayako Kobayashi, 51

1. Minamisoma (living at home)

2. Housewife

3. Every time she measures the radiation in the soil under her rain gutters it is 100 microsieverts, but her neighborhood is not in the designated evacuation area. “I want the government to offer an explanation that I can accept,” she said. She is concerned about the health of her two daughters, who are in their 20s. She has put contaminated soil in jars and is storing it.

Tomoko Shineha, 27

1. Minamisoma (moved to Soma)

2. Housewife

3. Her husband’s family grave is in the no-entry zone, so they were not able to visit it during the Bon holidays in August. “The government should consider the feelings of the Japanese people,” she said. She and her husband are discussing relocating his family grave outside the no-entry zone.

Tatsuya Suzuki, 29

1. Minamisoma (evacuated within the city)

2. Construction worker

3. In early August his daughter, 11, and son, 9, underwent checks for exposure to internal radiation at the municipal general hospital. Both of their results were below detectable limits. As for the government, he said, “I want them to make arrangements to offer regular examinations in the future.”

Shoichi Suzuki, 57

1. Minamisoma (living at home)

2. Lumber business, member of city council

3. His lumberyard, which employs four workers, continues to struggle, and he is concerned about whether or not he will be able to keep his workers on. With regard to the decontamination of contaminated soil in the city he said, “The government should announce a more specific schedule.”

Kenichi Yamazaki, 65

1. Minamisoma (evacuated to Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture)

2. Former high school teacher

3. “The prefecture should not only conduct health surveys but also make arrangements to provide medical treatment,” he said. A situation like the one in which the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) failed to provide treatment to the atomic bomb survivors must be avoided, he said.

Takumi Aizawa, 40

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Prefectural government employee

3. He was surprised that the municipality was considering setting up a location for the temporary storage of radioactive waste within the village. “The important thing is to get the understanding of the people before proceeding,” he said.

Mari Kobayashi, 46

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. NPO employee

3. She has been baffled by all the information on radiation and is mentally exhausted. She said she doesn’t know what to believe and wants mental health care to be provided to the residents.

Kenta Sato, 29

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Vice chair of the local junior chamber of commerce

3. Although the level of radiation in the village was high, the order to evacuate was delayed. “The government should release all of its information to the residents so they can use it to make decisions when taking action in the future.”

Tadayoshi Sato, 67

1. Iitate (evacuated to Date)

2. Farmer

3. He is concerned about the contamination of the soil. What he wants to know is when recovery can be expected. “If it is impossible, then the government should say that and tell us the truth.” He has no idea when he will be able to rebuild his life and is impatient.

Hachiro Sato, 59

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Farmer, member of town council

3. On the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima he met with survivors and talked with them. “The government underestimated the atomic bomb survivors’ internal exposure to radiation. If they intend to do the same thing with the accident at the nuclear power plant, the people of Fukushima Prefecture will not allow it.”

Mikiko Sato, 60

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Chair, village women’s society

3. She feels the sense of community, which she thought was the pride of Iitate, was lost with the accident at the nuclear power plant. “If we plant gardens and flower beds at our temporary housing, it may give the residents something to live for and also get people talking with one another,” she said.

Kenichi Takano, 60

1. Iitate (evacuated to Soma)

2. Company employee, livestock farmer

3. He has repeatedly asked the mayor of Iitate to convey his request to the government that the soil, which has been heavily contaminated with radiation, be cleaned up. “If the government does not take action, we will go on living with an uncertain future,” he said.

Yoshimune Hasegawa, 32

1. Iitate (evacuated to Yamagata Prefecture)

2. Dairy farmer

3. In early August he began working on a ranch in Yamagata Prefecture. He has accepted the fact that he may never be able to return to Iitate. “I would like to run a dairy farm in Fukushima Prefecture again,” he said. He stressed the need for government support.

Masako Kamata, 60

1. Katsurao (evacuated to Miharu)

2. Pig farmer

3. The compensation she received was gone as soon as she bought furniture and kitchenware. Her husband lost his job and is depressed. “The government should set up farms for the evacuees and offer support so that people can become independent,” she said.

Fumio Matsumoto, 59

1. Katsurao (evacuated to Miharu)

2. Construction worker

3. He, his 54-year-old brother and their ailing 88-year-old mother continue to live as evacuees. Their home is in the no-entry zone. He would like the government to proceed with decontamination as soon as possible. “I would like to take my mother home while she is still able to get around,” he said.

Aya Kikuchi, 17

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. High school student

3. She has made new friends in Nihonmatsu. The result of her test for exposure to internal radiation was “below measurable limits.” But, with regard to her health in the future, she said, “I’m still worried.” She would like the government to provide follow-up tests.

Hidezo Sato, 66

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Seed and plant business

3. He is concerned about the breakdown of the sense of community. Residents of the same jurisdiction are now scattered among temporary housing and evacuation centers. “I would like the government to create opportunities for residents of the same jurisdictions to get together with each other,” he said.

Seiichi Shiga, 57

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Restaurant management

3. There is still debris contaminated with radioactivity in Namie, inside the no-entry zone. He said that if people are not allowed to return to their residences no progress can be made on the town’s recovery. “The government should consider how to dispose of the debris as soon as possible,” he said.

Chihiro Suzuki, 18

1. Namie (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. High school student

3. After the accident at the nuclear power plant, she began living on her own in Iwaki, away from her family. “Every time there is an aftershock, I worry that there will be another explosion at the nuclear power plant,” she said. She wants the government to bring the accident to a conclusion as soon as possible.

Koji Suzuki, 58

1. Namie (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Fishing industry

3. The commercial fishing boat that he and his brother had used is still in the harbor in Namie, which is inside the no-entry zone. “It’s too bad that we can’t go out fishing in the fall, when the fish is really tasty,” he said. He wants the government to provide a way for him to return to commercial fishing.

Shunji Sekine, 69

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Doctor

3. He offers advice about evacuating to areas outside the prefecture to town residents who are worried about developing health problems. He would like the government to make use of Hiroshima’s knowledge and experience. “The effects of internal exposure to radiation must be thoroughly investigated,” he said.

Yoshihiko Monma, 32

1. Namie (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Singer/songwriter

3. Many people from Namie remain missing, but the large-scale search was called off. “I would like to see a prompt conclusion to the accident at the nuclear power plant and have my friends be found,” he said.

Shiro Yamada, 72

1. Namie (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Head of the Futaba regional agricultural mutual relief association

3. “The government should have the soil in the no-entry zone hauled away, and a city that the residents can move to as a group should be created,” he said. He feels that all they can do is live in such a city until the contaminated soil is completely cleaned up.

Nao Watanabe, 14

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Junior high school student

3. The result of his test for exposure to internal radiation was “below measurable limits,” but ever since the accident his throat feels funny. “I may not be able to return home. I would like the government to provide health checks for the rest of my life,” he said.

Miho Inoi, 23

1. Futaba (evacuated to Saitama Prefecture)

2. Part-time elementary school teacher

3. After the accident at the nuclear power plant she spent time outside doing various tasks such as preparing meals for the residents of evacuation centers. She wants to know the precise amount of radiation she has been exposed to. “The government should make it possible for everyone who wants to be tested for internal radiation to do so,” she said.

Akemi Obata, 44

1. Futaba (evacuated to Saitama Prefecture)

2. Agricultural cooperative employee

3. Life as an evacuee has become prolonged, and her health is not very good. “Everyone is stressed out,” she said. “The government should not just talk about a major recovery; they should take a look at the evacuees’ situations now.”

Yoshinori Tsuchida, 62

1. Futaba (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Retired carpenter

3. With the closure of his evacuation center, he moved to rental housing for disaster victims in early September. “How long will this life go on? I don’t suppose we will ever be able to return to our hometown,” he said with a tone of resignation.

Tomiko Nakamura, 60

1. Futaba (evacuated to Saitama Prefecture)

2. Chair of town women’s society

3. More and more Futaba residents are returning to Fukushima Prefecture from Saitama Prefecture. Right now it is left up to individuals to decide what to do. “The national and local government should provide more information to help people make decisions,” she said.

Fumihito Hayama, 35

1. Futaba (evacuated to Saitama Prefecture)

2. Operator of iron works

3. He is distressed because he is unable to pay the business partners who have supported him. “When deciding on a policy for paying compensation I would like the government to pay more attention to the evacuees’ personal difficulties,” he said.

Mitsuharu Yatsuda, 70

1. Futaba (evacuated to Tamura)

2. Farmer, member of town council

3. He has pinned his hopes on Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda, who said, “There will be no rebirth of Japan without the rebirth of Fukushima.” “If I can sense that the recovery is steadily proceeding, life as an evacuee will be somewhat bearable,” he said.

Masao Akimoto, 71

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizuwakamatsu)

2. Manager of fishing supply store, head of town children’s council

3. “Providing support for elderly people living alone in temporary housing is an issue,” he said. He is seeking the cooperation of the prefectural and municipal governments for a plan to have a social worker check on these residents.

Takeshi Ouchi, 62

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizuwakamatsu)

2. Farmer

3. His diabetes worsened as a result of stress, and he has been hospitalized since late August. “I would like the prefectural residents’ health survey to focus more on mental health care for the evacuees and not just check their internal exposure to radiation,” he said.

Ayaka Oga, 38

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizuwakamatsu)

2. Farmer

3. She is worried that baseless prejudice against residents of Fukushima Prefecture will increase. “I wonder what sort of suffering the atomic bomb survivors of Hiroshima experienced and what they did to prevent it,” she said.

Machiko Kikuchi, 59

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizuwakamatsu)

2. Part-time worker

3. She is fed up with the infighting in the Diet. “If they lived with the evacuees, they would get serious about considering recovery measures,” she said. She feels that the evacuees’ concerns are not being heard by the government.

Makoto Sato, 64

1. Okuma (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Straw mat manufacturing

3. He questions the fact that there are no evacuees among the members of the Dispute Reconciliation Committee for Nuclear Damage Compensation, which will decide on the compensation measures, and he is angry about that. “They should hear about the suffering in the disaster area directly,” he said.

Shuei Shiga, 69

1. Okuma (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Head of local agricultural cooperative

3. He feels that what is needed now is decontamination of farmland. He would like the amount of radioactivity to be gradually reduced until it approaches a condition at which farming is possible. “Measures must be taken so that farmers can see that progress is being made,” he said.

Yoshiko Suganami, 40

1. Okuma (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Judicial scrivener

3. Many evacuees have lost their homes and their jobs, and she feels it is important to provide support to them so they can get back on their feet. She wants to know about Hiroshima’s path to recovery. “The government should learn from the support provided to the atomic bomb survivors and the process by which Hiroshima recovered,” she said.

Minoru Yoshida, 63

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizuwakamatsu)

2. Former nuclear power plant worker

3. He has accepted the fact of his internal exposure to radiation calmly on account of his age. But, he said, “the government should take measures to ensure that everyone who wants to be tested for internal radiation exposure can do so.”

Nobuyuki Watanabe, 58

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizuwakamatsu)

2. Chairman of construction company, member of town council

3. He was angry at the government’s suggestion that it purchase the property in the no-entry zone and said it was “premature.” “First of all they should carry out thorough decontamination,” he said. “If the area is still not habitable, then they can talk about buying the land.”

Osamu Ando, 62

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Miharu)

2. Farmer, chief of local fire company

3. He feels the nuclear power plants in Japan should all be shut down. He hopes the voices of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will carry weight. “I would like the mayor of Hiroshima to call for the abandonment of nuclear power as the mayor of Nagasaki did,” he said.

Toshiro Kitamura, 66

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Sukagawa)

2. Participant, Japan Atomic Industrial Forum

3. Many of the evacuees are elderly people who can not use the Internet. “There must not be a gap in terms of access to information,” he said. “I would like the town to make an effort to ensure that information is conveyed equally to everyone.”

Tomoyuki Seki, 65

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Farmer, member of town council

3. “I would like the government to consider providing compensation that will allow the evacuees to live their lives free of anxiety,” he said. He feels it is difficult to plan ahead with compensation that is paid in a lump sum and believes that compensation paid regularly like a pension would be ideal.

Misao Sekine, 62

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Miharu)

2. Retired construction worker

3. Just after the accident at the nuclear power plant he felt tense, and now he drinks a lot. “I would like the government to create an environment that will allow the elderly to find jobs or other interests,” he said. He feels that having a purpose in life is important.

Kimio Akimoto, 63

1. Kawauchi (evacuated to Tamura)

2. Head of the Futaba regional forestry cooperative

3. As a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant it is no longer possible to maintain the forests in the Futaba region and they are degrading. “We should resume logging starting in areas with low levels of radiation,” he said. He believes this would also create jobs.

Yoshitoyo Sakuma, 29

1. Kawauchi (evacuated to Koriyama)

2. Former employee of auto repair shop

3. After the accident at the nuclear power plant he skipped work and was fired. In order to restore his employer’s confidence in him, he has been working without pay. “If we get more work I may be able to get my job back,” he said. “I hope a path to recovery will be found as soon as possible.”

Chido Sakuma, 29

1. Naraha (evacuated to Sendai)

2. Buddhist priest

3. Although he had not yet been assigned temporary housing, the evacuation center where he had been staying closed at the end of August. “I’m tired of having to keep moving from one place to another,” he said. “I want the government to provide a place where I can settle down as soon as possible.”

Kazuhiro Matsumoto, 41

1. Naraha (evacuated to Aizumisato)

2. Employee of electrical company

3. His workplace is inside the no-entry zone, so it is still shut down. “With just my leave allowance and the compensation, I can’t repay the loan I took out to build a new home,” he said. He would like the government to come up with measures to assist those who have been forced to take leave from their jobs.

Rie Abe, 40

1. Hirono (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Housewife

3. Her home is outside the no-entry zone, and she stayed there several times during the summer vacation. Friends from Okuma and Futaba complain that they will never be able to return home. “I would like to hear specific plans for decontamination of the land,” she said.

Kazumasa Komatsu, 42

1. Hirono (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Municipal employee

3. His home is in an area where the amount of radiation is comparatively low. In terms of recovery-related issues, in addition to decontamination of the land, he said, “It is also necessary to rebuild infrastructure such as the public transportation system and places to go shopping,” he said.

Fukushima Prefecture Health Survey of Residents

A health survey of the approximately 2 million residents of Fukushima Prefecture will be conducted in two stages: a basic survey consisting of a questionnaire followed by a detailed survey, which will include an ultrasound examination of the thyroid gland.

Mailing out of the questionnaires for the basic survey began in late August. Residents are being asked to record their activities in the days after the accident at the nuclear power plant and where they were staying. This information is correlated with the government’s radiation dose values and other data to determine the amount of each individual’s external exposure to radiation.

The detailed survey is scheduled to begin in October. About 360,000 people who were 18 or under at the time of the accident will undergo initial thyroid examinations by March 2014. They will continue to undergo regular follow-up examinations throughout their lives. The approximately 200,000 residents of the designated evacuation area will undergo health checks that will include thorough testing of their blood and urine. The effects of the accident on their mental health will also be investigated, and pregnant women and nursing mothers will be given a separate questionnaire.

In some areas, such as Namie and Iitate where radiation levels are high, the health survey was begun in late June.

(Originally published on September 14, 2011)