Fukushima and Hiroshima: Harmful rumors swirl in a merciless autumn

Oct. 24, 2011

by Seiji Shitakubo, Yoko Yamamoto, Kei Kinugawa, and Yo Kono, Staff Writers

There seems to be no end to the harmful rumors that have spread in the wake of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Ordinarily, the autumn is the time of a joyful harvest, but this year, Fukushima Prefecture has greeted the season with sweeping anxiety. Even fireworks produced within the prefecture were rejected for use outside the area. Words of prejudice and slander, such as accusations of spreading radiation to others, pain the hearts of evacuees. People of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima once suffered the same experience. Is it all right to eat the foods which have cleared the standards set for radiation? What should be of concern to us? The Chugoku Shimbun investigates these issues.

“It broke my heart,” said Isao Sato, 62, who lives in the city of Date in Fukushima Prefecture. He was recalling how he was forced to dig a pit on his farm to dispose of the peaches he grows for processing juice. The peaches harvested in the city had cleared the standard set by the Japanese government for radiation exposure, but the beverage companies would no longer accept his deliveries.

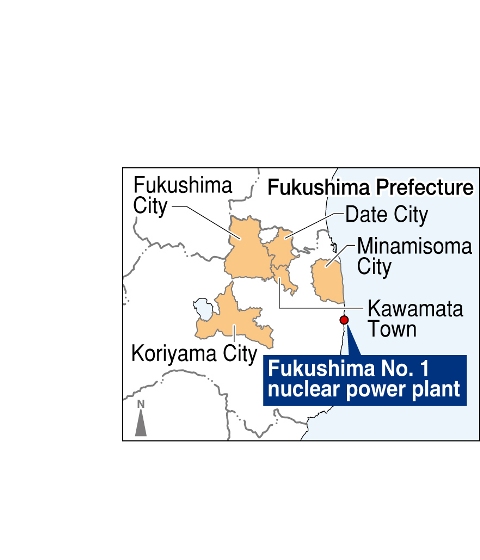

Fukushima Prefecture produces the second largest crop of peaches in Japan, following Yamanashi Prefecture. The city of Date, lying about 50 kilometers northwest of the crippled nuclear plant, boasts flourishing peach orchards. In the wake of the accident, the wholesale price for “gift peaches” nosedived to a level one-fifth of their previous price. The Fukushima Prefectural Council for Compensation Measure, comprised of the Japanese Agricultural Cooperative (JA) and other entities, estimates that the losses caused by rumors of contaminated crops to be as high as 2.3 billion yen.

Mr. Sato grows rice, vegetables, and fruits on his farm of roughly 1.4 hectares. After harvesting his rice in the fall, he prepares dried persimmons in the winter. “It will take a long time for the reputation of Fukushima farm products to recover,” he said. “At this rate, there won’t be anyone willing to engage in farming in Fukushima.”

In late September, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) announced a policy for compensation in connection with the rumors that have harmed the livelihoods of those affected by the nuclear accident. Norio Tsuzumi, the vice president of TEPCO, stressed, “We will provide compensation as long as losses exist.” But he did not elaborate on the criteria the company will use in determining the end of such losses.

TEPCO’s criteria for compensating losses

In principle, the people and businesses within the designated evacuation areas that have been engaged in agriculture, fishing, and manufacturing may be compensated for lost income as a result of the accident. Regarding rumors that have harmed sales, farm products from six prefectures, namely Fukushima, Tochigi, Gunma, Chiba, Ibaraki, and Saitama, are covered. The amount of compensation will be determined with respect to the average prices of such products nationwide.

Losses caused by rumors impacting the tourism industry in areas lying outside the designated evacuation areas in Fukushima Prefecture, as well as the prefectures of Ibaraki, Tochigi, and Gunma, will receive compensation equal to 80% of their normal income. The deduction of 20% percent is considered the drop in income as an effect of the earthquake and tsunami alone, if the nuclear accident had not occurred. TEPCO will begin issuing this compensation in mid-October, and payments will be made every three months.

With his lips trembling in anger, Tadao Kanno, 78, said, “If such prejudice continues, the manufacturers in Fukushima Prefecture will all go out of business.” Mr. Kanno owns a company that makes fireworks in the town of Kawamata, Fukushima Prefecture. Eighty fireworks produced by his company were rebuffed for a fireworks display held in the city of Nisshin, in Aichi Prefecture, on September 18.

The reason for this refusal: “Those fireworks could spread radiation.” After receiving more than 20 email messages and telephone calls protesting the use of the Fukushima fireworks, the committee in charge of the fireworks display, comprised of the municipal government and the city’s commerce and industry association, decided to replace the fireworks made in Fukushima Prefecture with ones made in Aichi Prefecture.

Afterwards, the Nisshin city government inspected the fireworks from Fukushima Prefecture and found that two of the fireworks contained approximately 50 becquerels of cesium per kilogram. As this level of radiation is significantly lower than the current limit for grains and vegetables, at 500 becquerels per kilogram, a city official said, “The city has confirmed the safety of the fireworks and plans to use them in the future.”

The problem is not limited to goods from Fukushima Prefecture. At a traditional ceremony held in the city of Kyoto in August, in which bonfires are lit on the sides of mountains, the idea of including timber from Iwate Prefecture to mourn those who perished in the tsunami was scuttled due to fears of radiation from that region. Another example involves the cancellation of an art exhibition, slated for Japan, that was coming from a museum overseas.

What criteria should be used to differentiate the safe from the potentially hazardous? Hiromi Yamazawa, a professor of environmental radiation studies at Nagoya University, proposes that we “compare the level of radiation of particular things with the radiation that exists around us ordinarily.” He explained by pointing to the concern felt by the city of Nisshin over the fireworks from Fukushima Prefecture.

If a firework with a level of 50 becquerels of radiation exploded in the air and was spread out in the form of a cube 10 meters per side, the level of radiation per one cubic meter would be 0.05 becquerels. In nature itself, each cubic meter holds about 10 becquerels of radioactive materials, including radon. “If we look at this situation from a scientific perspective,” stressed Professor Yamazawa, “we can see that this amount of radiation will pose no problem. We need to keep a cool head when we react to such situations.”

Food items, including rice and vegetables, cannot be shipped unless they meet the standards set by the Japanese government for radiation exposure. Yet radiation amounts that exceed these standards continue to be detected in such foods as spinach, bamboo shoots, tea leaves, and wheat, stirring anxiety among the public. People are coming to doubt whether the safety of the food supply can actually be secured. Meanwhile, questions have been raised regarding the appropriateness of the standards themselves. The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) is poised to conduct a through review of these standards soon.

The current standards were established by the central government on March 17, six days after the accident at the nuclear plant. These standards are based on the following criteria.

First, for an individual’s annual food consumption, the government set a limit for radiation exposure of five millisieverts from cesium and two millisieverts from iodine. As these standards had not already been in place, they were based on similar information specified in guidelines compiled by the Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan for emergency situations.

In terms of cesium, the standard of five millisieverts was divided into five categories: water; milk and dairy products; vegetables; grains; and meat, eggs, fish, and other items. To establish a limit of one millisievert for each category, the government determined amounts of 200 becquerels per kilogram of water, milk, and dairy products and 500 becquerels for meat, vegetables, and grains, basing these calculations on the average intake of food.

But standards such as this should apply only in the event of an emergency. Twenty-five years have passed since the accident occurred at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union. In Ukraine today, the standard for cesium still stands at 20 becquerels per kilogram of bread. This standard is very strict, as low as one twenty-fifth of the standard for grains in Japan. The Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan and other entities point out that “restrictions set in an emergency should not be maintained beyond those emergency conditions.”

In July, the Food Safety Commission offered the view that “radiation exposure over a person’s lifetime should be limited to a maximum accumulation of 100 millisieverts.” This view, which is prompting the move for stricter regulations, will be taken into consideration as the MHLW pursues its review of the current standards for radiation exposure. The government is likely to set a new standard aimed specifically at babies and toddlers, along the lines of the international standard established by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, an intergovernmental body.

After this review, the possibility exists that products from a number of areas may exceed the revised standards. But after examining a variety of materials inside and outside Japan that concern the effects of radiation, the Food Safety Commission, chaired by Naoko Koizumi, revealed: “The amount of data regarding internal exposure to radiation is not sufficient.” It is still unclear whether or not the review will be able to devise “concrete” standards for food safety.

What should the people of Japan do to combat the problem of food contaminated by radiation? The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Toru Hayashi, a professor at Seitoku University, for points to consider and the challenges ahead. As the former director of the National Food Research Institute, Mr. Hayashi has pursued research in this area through such means as irradiating food samples.

To what extent does consumption of contaminated food harm our health?

Current expertise estimates that one millisievert of exposure to radiation will increase the incidence of cancer by 0.005%.

Following the accident, I undertook my own calculations concerning the incidence of cancer deaths, based upon information from the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) and other organizations. In the case of a person who consumes food contaminated with radiation amounting to 500 becquerels per kilogram, and does this each day for a year, the incidence of dying from cancer rises by 0.024 percent. This is actually an unrealistic assumption. It depends on the individual as to how this figure is viewed.

What countermeasures can be taken?

According to the Radioactive Waste Management Funding and Research Center, when food is washed or boiled, the radiation contamination can be reduced from as little as 10 percent to as much as 90 percent. The point is that the central government must conduct examinations of the food supply in a manner that inspires confidence and the people of Japan are then faced with making personal judgments on how much risk they will take.

To this point, people have lived with little awareness of radiation, and they’re now bewildered. They need reliable information so they can assess the risks and then act.

What precautions should people take?

The effects of low doses of radiation on the human body are still unclear. Objections have been raised with regard to the standards set by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). As babies and small children are most susceptible to the effects of radiation, it’s vital to make efforts to reduce their level of exposure to radiation as much as possible.

Radiation harms genes. But it is believed that, rather than a direct effect, this damage is more the result of an “indirect effect,” whereby the surrounding reactive oxygen species (ROS), chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen, among other things, damage the DNA. A lifestyle that seeks to decrease the ROS is an important precaution, too.

In other words, if people are overly concerned about being exposed to radiation and end up eating fewer vegetables or their immunity is weakened due to stress, they will be undermining their own aims. To cope with radiation, we must learn about it. For instance, if we don’t have a basic knowledge of the subject and are unfamiliar with the meanings of terminology like “becquerels” and “sieverts,” we won’t be able to understand that sort of information. It’s the duty of the Japanese government to provide the public with information, in a timely manner, that people will find easy to understand.

Profile

Toru Hayashi

Mr. Hayashi was born in Kyoto in 1950. He graduated from the Faculty of Agriculture at Kyoto University. After serving as a researcher at the National Food Research Institute, he became the director of that institute, under the auspices of the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, in 2006. Since 2010, he has been a professor at Seitoku University in Matsudo, Chiba Prefecture.

In the wake of inappropriate remarks he made in the areas affected by the nuclear crisis, including a joke about sullying a reporter with radiation, Yoshio Hachiro, the minister of Economy, Trade and Industry took responsibility for these gaffes by stepping down from his post. When Ryutaro Hanawa, 33, a care-giver in the city of Minamisoma, Fukushima Prefecture, heard the news on September 10, he felt outraged, as he has suffered the same distressing treatment.

In mid-March, Mr. Hanawa stopped into a convenience store on his way to Yamanashi Prefecture, where his wife’s parents live. When he came out of the store, some local children surrounded his car, which bears a Fukushima license plate. “It has radiation,” the children said. “Don’t touch it.” The children were apparently joking, but Mr. Hanawa was nevertheless shocked by the experience.

The Fukushima Prefecture Disaster Countermeasure Headquarters has received a number of reports concerning the cancellation of reservations at local inns, bullying, graffiti, and other incidents. “People should think of the feelings of the people who are suffering,” Mr. Hanawa said.

“Schools must take action to abolish prejudice and slander,” said a spokesperson for the Japan Environmental Education Society, chaired by Rikkyo University professor Osamu Abe. The association, comprised of some 1,700 teachers and researchers, has crafted a lesson plan for “moral education” classes.

The lesson plan seeks for students to ponder the subject of bullying toward the sufferers of the nuclear disaster through the use of newspaper articles and other resources. Eiko Takagi, 58, a teacher at Kogane Junior High School in Matsudo, Chiba Prefecture, taught a lesson based on this plan. “The important thing is being thoughtful toward the people who are suffering,” she said. “Instead of simply lecturing and instructing, I would like to think about the issue together with my students.”

Accurate information is not being conveyed

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Hiroshi Nunokawa, a professor of modern Japanese history in the graduate school at Hiroshima University, about the social problems that have arisen in the wake of the accident in Fukushima Prefecture. Professor Nunokawa is well-versed in the problem of prejudice and slander suffered by the A-bomb survivors. The following comments by Professor Nunokawa are excerpts from this interview.

In the post-war period, the health effects caused by the radiation released from the atomic bombs were not well understood, and this led to exaggerated fears. In the case of Fukushima, the public is being saturated with information, which may or may not be accurate, and various experts have cited differing safety standards. The common denominator of both the atomic bombings and this nuclear disaster is that people are not receiving accurate information.

When people panic in reaction to a crisis, unfounded rumors tend to be bred. To this point, the people of Japan have been unable to chart a way of coping with the situation calmly.

The leader of the nation must get out the message that all our citizens should share the risk. If the leader explains the situation thoroughly and earns the public’s understanding, this would inspire each one of us to lend our support to the people most affected by the accident. Then the prejudice will fade and the recovery from this disaster can move forward more swiftly.

“I feel very sorry for the people of Fukushima,” said Haruko Katayama, 81. Ms. Katayama lives in Asaminami Ward and serves as the chairperson of the Hiroshima City Association of Atomic Bomb Sufferers.

Sixty-six years ago, she was exposed to the bomb at a location 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. As a result of rumors that the survivors’ exposure to the bombing could effect their offspring, Ms. Katayama was rejected three times when she sought an arranged marriage. Still, she later married and gave birth to a baby girl. She said that her daughter is now in her 40s and her health is good.

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) in Hiroshima has long been engaged in follow-up studies on A-bomb survivors. In 2007, RERF announced that it had found “no evidence of increased risk” of disease for second-generation A-bomb survivors as a result of their parents exposure to the radiation emitted by the atomic bomb. “Even now, I feel hurt by those rumors,” Ms. Katayama said.

In 2006, the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi, conducted a survey that reached about 7,400 A-bomb survivors. Among the respondents, 29% said that “I suffered from the rumor that A-bomb survivors would not live very long,” and 28% said that “I felt that rumors were an obstacle to getting married.”

What measures has the A-bombed city of Hiroshima been pursuing to address such prejudice? About 80 percent of elementary school and junior high schools in the city arrange opportunities each year for their students to listen to the accounts of A-bomb survivors. In addition, all students pay a visit to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum during their schooling. The Hiroshima City Board of Education seeks to have peace education “linked to the study of human rights and values.” And to respond to the concerns of A-bomb survivors, the City of Hiroshima has put counseling staff in place at city hall and at other locations since 1973.

Due to the nuclear accident, Marie Inoue, 37, and her family evacuated from the city of Koriyama in Fukushima Prefecture to Nishi Ward, Hiroshima. “I’m so relieved that children from Fukushima aren’t experiencing any bullying in Hiroshima,” she said. Her oldest son, Taichi, 7, seems happy to be attending elementary school in Nishi Ward each day.

Kunihiko Sakuma, 66, vice chairman of another faction of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Kazushi Kaneko, has been serving as a counselor for A-bomb survivors for five and half years. During his time as a counselor, he has become aware of the deeply-rooted prejudice and discrimination suffered by A-bomb survivors.

To date, he has listened to the distress of about 10 evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture and shared with them his experience of the atomic bombing. “We can understand the suffering of the people of Fukushima,” he said. “So we would like to be of help to them.”

(Originally published on October 4, 2011)

There seems to be no end to the harmful rumors that have spread in the wake of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Ordinarily, the autumn is the time of a joyful harvest, but this year, Fukushima Prefecture has greeted the season with sweeping anxiety. Even fireworks produced within the prefecture were rejected for use outside the area. Words of prejudice and slander, such as accusations of spreading radiation to others, pain the hearts of evacuees. People of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima once suffered the same experience. Is it all right to eat the foods which have cleared the standards set for radiation? What should be of concern to us? The Chugoku Shimbun investigates these issues.

Farm products

Farmers suffer rejection of their products and a sharp fall in prices

“It broke my heart,” said Isao Sato, 62, who lives in the city of Date in Fukushima Prefecture. He was recalling how he was forced to dig a pit on his farm to dispose of the peaches he grows for processing juice. The peaches harvested in the city had cleared the standard set by the Japanese government for radiation exposure, but the beverage companies would no longer accept his deliveries.

Fukushima Prefecture produces the second largest crop of peaches in Japan, following Yamanashi Prefecture. The city of Date, lying about 50 kilometers northwest of the crippled nuclear plant, boasts flourishing peach orchards. In the wake of the accident, the wholesale price for “gift peaches” nosedived to a level one-fifth of their previous price. The Fukushima Prefectural Council for Compensation Measure, comprised of the Japanese Agricultural Cooperative (JA) and other entities, estimates that the losses caused by rumors of contaminated crops to be as high as 2.3 billion yen.

Mr. Sato grows rice, vegetables, and fruits on his farm of roughly 1.4 hectares. After harvesting his rice in the fall, he prepares dried persimmons in the winter. “It will take a long time for the reputation of Fukushima farm products to recover,” he said. “At this rate, there won’t be anyone willing to engage in farming in Fukushima.”

In late September, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) announced a policy for compensation in connection with the rumors that have harmed the livelihoods of those affected by the nuclear accident. Norio Tsuzumi, the vice president of TEPCO, stressed, “We will provide compensation as long as losses exist.” But he did not elaborate on the criteria the company will use in determining the end of such losses.

TEPCO’s criteria for compensating losses

In principle, the people and businesses within the designated evacuation areas that have been engaged in agriculture, fishing, and manufacturing may be compensated for lost income as a result of the accident. Regarding rumors that have harmed sales, farm products from six prefectures, namely Fukushima, Tochigi, Gunma, Chiba, Ibaraki, and Saitama, are covered. The amount of compensation will be determined with respect to the average prices of such products nationwide.

Losses caused by rumors impacting the tourism industry in areas lying outside the designated evacuation areas in Fukushima Prefecture, as well as the prefectures of Ibaraki, Tochigi, and Gunma, will receive compensation equal to 80% of their normal income. The deduction of 20% percent is considered the drop in income as an effect of the earthquake and tsunami alone, if the nuclear accident had not occurred. TEPCO will begin issuing this compensation in mid-October, and payments will be made every three months.

Fireworks rebuffed

Sense of crisis over manufacturing in Fukushima Prefecture

With his lips trembling in anger, Tadao Kanno, 78, said, “If such prejudice continues, the manufacturers in Fukushima Prefecture will all go out of business.” Mr. Kanno owns a company that makes fireworks in the town of Kawamata, Fukushima Prefecture. Eighty fireworks produced by his company were rebuffed for a fireworks display held in the city of Nisshin, in Aichi Prefecture, on September 18.

The reason for this refusal: “Those fireworks could spread radiation.” After receiving more than 20 email messages and telephone calls protesting the use of the Fukushima fireworks, the committee in charge of the fireworks display, comprised of the municipal government and the city’s commerce and industry association, decided to replace the fireworks made in Fukushima Prefecture with ones made in Aichi Prefecture.

Afterwards, the Nisshin city government inspected the fireworks from Fukushima Prefecture and found that two of the fireworks contained approximately 50 becquerels of cesium per kilogram. As this level of radiation is significantly lower than the current limit for grains and vegetables, at 500 becquerels per kilogram, a city official said, “The city has confirmed the safety of the fireworks and plans to use them in the future.”

The problem is not limited to goods from Fukushima Prefecture. At a traditional ceremony held in the city of Kyoto in August, in which bonfires are lit on the sides of mountains, the idea of including timber from Iwate Prefecture to mourn those who perished in the tsunami was scuttled due to fears of radiation from that region. Another example involves the cancellation of an art exhibition, slated for Japan, that was coming from a museum overseas.

What criteria should be used to differentiate the safe from the potentially hazardous? Hiromi Yamazawa, a professor of environmental radiation studies at Nagoya University, proposes that we “compare the level of radiation of particular things with the radiation that exists around us ordinarily.” He explained by pointing to the concern felt by the city of Nisshin over the fireworks from Fukushima Prefecture.

If a firework with a level of 50 becquerels of radiation exploded in the air and was spread out in the form of a cube 10 meters per side, the level of radiation per one cubic meter would be 0.05 becquerels. In nature itself, each cubic meter holds about 10 becquerels of radioactive materials, including radon. “If we look at this situation from a scientific perspective,” stressed Professor Yamazawa, “we can see that this amount of radiation will pose no problem. We need to keep a cool head when we react to such situations.”

Questions raised about food safety levels

Health ministry plans to set stricter standards

Food items, including rice and vegetables, cannot be shipped unless they meet the standards set by the Japanese government for radiation exposure. Yet radiation amounts that exceed these standards continue to be detected in such foods as spinach, bamboo shoots, tea leaves, and wheat, stirring anxiety among the public. People are coming to doubt whether the safety of the food supply can actually be secured. Meanwhile, questions have been raised regarding the appropriateness of the standards themselves. The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) is poised to conduct a through review of these standards soon.

The current standards were established by the central government on March 17, six days after the accident at the nuclear plant. These standards are based on the following criteria.

First, for an individual’s annual food consumption, the government set a limit for radiation exposure of five millisieverts from cesium and two millisieverts from iodine. As these standards had not already been in place, they were based on similar information specified in guidelines compiled by the Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan for emergency situations.

In terms of cesium, the standard of five millisieverts was divided into five categories: water; milk and dairy products; vegetables; grains; and meat, eggs, fish, and other items. To establish a limit of one millisievert for each category, the government determined amounts of 200 becquerels per kilogram of water, milk, and dairy products and 500 becquerels for meat, vegetables, and grains, basing these calculations on the average intake of food.

But standards such as this should apply only in the event of an emergency. Twenty-five years have passed since the accident occurred at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union. In Ukraine today, the standard for cesium still stands at 20 becquerels per kilogram of bread. This standard is very strict, as low as one twenty-fifth of the standard for grains in Japan. The Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan and other entities point out that “restrictions set in an emergency should not be maintained beyond those emergency conditions.”

In July, the Food Safety Commission offered the view that “radiation exposure over a person’s lifetime should be limited to a maximum accumulation of 100 millisieverts.” This view, which is prompting the move for stricter regulations, will be taken into consideration as the MHLW pursues its review of the current standards for radiation exposure. The government is likely to set a new standard aimed specifically at babies and toddlers, along the lines of the international standard established by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, an intergovernmental body.

After this review, the possibility exists that products from a number of areas may exceed the revised standards. But after examining a variety of materials inside and outside Japan that concern the effects of radiation, the Food Safety Commission, chaired by Naoko Koizumi, revealed: “The amount of data regarding internal exposure to radiation is not sufficient.” It is still unclear whether or not the review will be able to devise “concrete” standards for food safety.

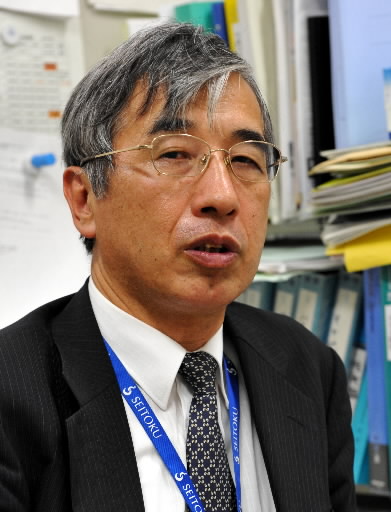

Interview with Toru Hayashi, former director of the National Food Research Institute

What should be done to combat the contamination of food?

What should the people of Japan do to combat the problem of food contaminated by radiation? The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Toru Hayashi, a professor at Seitoku University, for points to consider and the challenges ahead. As the former director of the National Food Research Institute, Mr. Hayashi has pursued research in this area through such means as irradiating food samples.

To what extent does consumption of contaminated food harm our health?

Current expertise estimates that one millisievert of exposure to radiation will increase the incidence of cancer by 0.005%.

Following the accident, I undertook my own calculations concerning the incidence of cancer deaths, based upon information from the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) and other organizations. In the case of a person who consumes food contaminated with radiation amounting to 500 becquerels per kilogram, and does this each day for a year, the incidence of dying from cancer rises by 0.024 percent. This is actually an unrealistic assumption. It depends on the individual as to how this figure is viewed.

What countermeasures can be taken?

According to the Radioactive Waste Management Funding and Research Center, when food is washed or boiled, the radiation contamination can be reduced from as little as 10 percent to as much as 90 percent. The point is that the central government must conduct examinations of the food supply in a manner that inspires confidence and the people of Japan are then faced with making personal judgments on how much risk they will take.

To this point, people have lived with little awareness of radiation, and they’re now bewildered. They need reliable information so they can assess the risks and then act.

What precautions should people take?

The effects of low doses of radiation on the human body are still unclear. Objections have been raised with regard to the standards set by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). As babies and small children are most susceptible to the effects of radiation, it’s vital to make efforts to reduce their level of exposure to radiation as much as possible.

Radiation harms genes. But it is believed that, rather than a direct effect, this damage is more the result of an “indirect effect,” whereby the surrounding reactive oxygen species (ROS), chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen, among other things, damage the DNA. A lifestyle that seeks to decrease the ROS is an important precaution, too.

In other words, if people are overly concerned about being exposed to radiation and end up eating fewer vegetables or their immunity is weakened due to stress, they will be undermining their own aims. To cope with radiation, we must learn about it. For instance, if we don’t have a basic knowledge of the subject and are unfamiliar with the meanings of terminology like “becquerels” and “sieverts,” we won’t be able to understand that sort of information. It’s the duty of the Japanese government to provide the public with information, in a timely manner, that people will find easy to understand.

Profile

Toru Hayashi

Mr. Hayashi was born in Kyoto in 1950. He graduated from the Faculty of Agriculture at Kyoto University. After serving as a researcher at the National Food Research Institute, he became the director of that institute, under the auspices of the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, in 2006. Since 2010, he has been a professor at Seitoku University in Matsudo, Chiba Prefecture.

Prejudice and slander continue

Bullying, graffiti, and other acts hurt the victims

In the wake of inappropriate remarks he made in the areas affected by the nuclear crisis, including a joke about sullying a reporter with radiation, Yoshio Hachiro, the minister of Economy, Trade and Industry took responsibility for these gaffes by stepping down from his post. When Ryutaro Hanawa, 33, a care-giver in the city of Minamisoma, Fukushima Prefecture, heard the news on September 10, he felt outraged, as he has suffered the same distressing treatment.

In mid-March, Mr. Hanawa stopped into a convenience store on his way to Yamanashi Prefecture, where his wife’s parents live. When he came out of the store, some local children surrounded his car, which bears a Fukushima license plate. “It has radiation,” the children said. “Don’t touch it.” The children were apparently joking, but Mr. Hanawa was nevertheless shocked by the experience.

The Fukushima Prefecture Disaster Countermeasure Headquarters has received a number of reports concerning the cancellation of reservations at local inns, bullying, graffiti, and other incidents. “People should think of the feelings of the people who are suffering,” Mr. Hanawa said.

“Schools must take action to abolish prejudice and slander,” said a spokesperson for the Japan Environmental Education Society, chaired by Rikkyo University professor Osamu Abe. The association, comprised of some 1,700 teachers and researchers, has crafted a lesson plan for “moral education” classes.

The lesson plan seeks for students to ponder the subject of bullying toward the sufferers of the nuclear disaster through the use of newspaper articles and other resources. Eiko Takagi, 58, a teacher at Kogane Junior High School in Matsudo, Chiba Prefecture, taught a lesson based on this plan. “The important thing is being thoughtful toward the people who are suffering,” she said. “Instead of simply lecturing and instructing, I would like to think about the issue together with my students.”

Accurate information is not being conveyed

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Hiroshi Nunokawa, a professor of modern Japanese history in the graduate school at Hiroshima University, about the social problems that have arisen in the wake of the accident in Fukushima Prefecture. Professor Nunokawa is well-versed in the problem of prejudice and slander suffered by the A-bomb survivors. The following comments by Professor Nunokawa are excerpts from this interview.

In the post-war period, the health effects caused by the radiation released from the atomic bombs were not well understood, and this led to exaggerated fears. In the case of Fukushima, the public is being saturated with information, which may or may not be accurate, and various experts have cited differing safety standards. The common denominator of both the atomic bombings and this nuclear disaster is that people are not receiving accurate information.

When people panic in reaction to a crisis, unfounded rumors tend to be bred. To this point, the people of Japan have been unable to chart a way of coping with the situation calmly.

The leader of the nation must get out the message that all our citizens should share the risk. If the leader explains the situation thoroughly and earns the public’s understanding, this would inspire each one of us to lend our support to the people most affected by the accident. Then the prejudice will fade and the recovery from this disaster can move forward more swiftly.

Victims of prejudice themselves, A-bomb survivors offer support

“I feel very sorry for the people of Fukushima,” said Haruko Katayama, 81. Ms. Katayama lives in Asaminami Ward and serves as the chairperson of the Hiroshima City Association of Atomic Bomb Sufferers.

Sixty-six years ago, she was exposed to the bomb at a location 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. As a result of rumors that the survivors’ exposure to the bombing could effect their offspring, Ms. Katayama was rejected three times when she sought an arranged marriage. Still, she later married and gave birth to a baby girl. She said that her daughter is now in her 40s and her health is good.

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) in Hiroshima has long been engaged in follow-up studies on A-bomb survivors. In 2007, RERF announced that it had found “no evidence of increased risk” of disease for second-generation A-bomb survivors as a result of their parents exposure to the radiation emitted by the atomic bomb. “Even now, I feel hurt by those rumors,” Ms. Katayama said.

In 2006, the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi, conducted a survey that reached about 7,400 A-bomb survivors. Among the respondents, 29% said that “I suffered from the rumor that A-bomb survivors would not live very long,” and 28% said that “I felt that rumors were an obstacle to getting married.”

What measures has the A-bombed city of Hiroshima been pursuing to address such prejudice? About 80 percent of elementary school and junior high schools in the city arrange opportunities each year for their students to listen to the accounts of A-bomb survivors. In addition, all students pay a visit to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum during their schooling. The Hiroshima City Board of Education seeks to have peace education “linked to the study of human rights and values.” And to respond to the concerns of A-bomb survivors, the City of Hiroshima has put counseling staff in place at city hall and at other locations since 1973.

Due to the nuclear accident, Marie Inoue, 37, and her family evacuated from the city of Koriyama in Fukushima Prefecture to Nishi Ward, Hiroshima. “I’m so relieved that children from Fukushima aren’t experiencing any bullying in Hiroshima,” she said. Her oldest son, Taichi, 7, seems happy to be attending elementary school in Nishi Ward each day.

Kunihiko Sakuma, 66, vice chairman of another faction of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Kazushi Kaneko, has been serving as a counselor for A-bomb survivors for five and half years. During his time as a counselor, he has become aware of the deeply-rooted prejudice and discrimination suffered by A-bomb survivors.

To date, he has listened to the distress of about 10 evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture and shared with them his experience of the atomic bombing. “We can understand the suffering of the people of Fukushima,” he said. “So we would like to be of help to them.”

(Originally published on October 4, 2011)