Fukushima and Hiroshima: Reconstruction and Reality, Part 7 [2]

Dec. 15, 2011

Article 2: Temporary storage of waste

by Seiji Shitakubo and Yo Kono, Staff Writers

Offering sites for storage vexes local residents

The comments made by Goshi Hosono, the state minister charged with overseeing the response to the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, as well as other government officials, have stressed their determination: “We will do a thorough job of decontaminating the affected areas” and “We will undertake these efforts without concern over the cost.” The reality, however, is more complicated. First of all, where will the contaminated soil and plants and trees be put? The people of Fukushima Prefecture are troubled by the issue involving temporary storage of the waste.

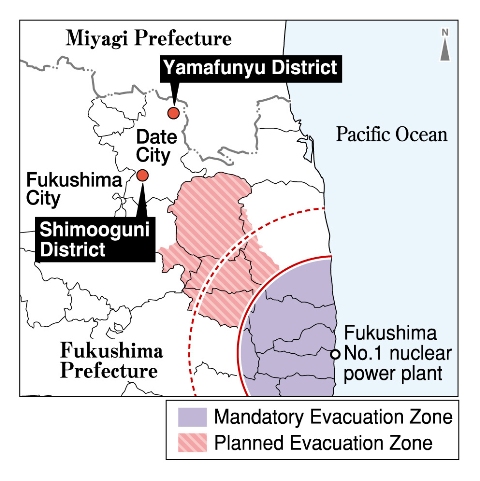

Along the road in the Yamafunyu district, which lies in the city of Date, some 60 kilometers northwest of the nuclear plant, are a number of signs bearing such messages as “We refuse to be a site for radioactive waste” and “Keep our children safe.”

Protest by residents of mountainous district

The protest by these local residents began in August when Date officials hinted at turning a former rock quarry, adjacent to the Yamafunyu district, into a temporary storage site for waste from the decontamination work. Almost 1,000 residents from the mountainous district launched a coordinated protest, arguing that the ground water would become contaminated and that children and their families would flee the area out of health concerns.

The decontamination work will produce a massive amount of waste. The central government has asked each municipality to identify a local site for the temporary storage of this waste. The idea involves holding the waste at these sites for about three years and then gathering it for storage at large-scale interim facilities. Within 30 years, the central government would then secure the final disposal site outside Fukushima Prefecture.

“Temporary storage sites must be secured before the decontamination work can proceed,” the government insists. But the fear of exposure to radiation has prevented the residents of any location from welcoming such a site for waste. And with little progress being made in this vein, decontamination efforts have advanced slowly, and the reconstruction of the affected areas remains stymied.

But how was the soil of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, contaminated with radiation, disposed of 66 years ago?

“Ultimately, Hiroshima didn’t undertake any special measures,” explained Hiromi Hasai, a professor emeritus in nuclear physics at Hiroshima University. Professor Hasai is also a hibakusha, or A-bomb survivor.

Debris was held in bare hands

At the time of the atomic bombing, Hiroshima citizens and local governments were not yet aware of the effects of radiation on the human body. As a result, people grabbed the debris with their bare hands to dispose of it, while around the hypocenter, the land was covered over with a layer of soil. Even to this day, the debris from the bombing is buried under Peace Memorial Park in downtown Hiroshima. In fact, in the year 2000, when Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall was under construction, a number of burnt roof tiles and bricks were found in a layer of earth about 15 centimeters below the surface soil.

The volume of radioactive Cesium leaked in the accident at the Fukushima plant is estimated to be 168.5 times as great as the amount of Cesium released in the air in the wake of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. “Two weeks after the bombing,” Professor Hasai said, “it’s believed that the dose of residual radiation fell to a level not likely to affect human health.” Regrettably, Hiroshima’s experience cannot be applied to the situation in Fukushima.

The New Year’s holiday is approaching. “Everyone wants to welcome the new year with their children and grandchildren,” said Mikio Sato, 70, a farmer in the Shimooguni district in Date. Mr. Sato has rented some of his land, about 1,400 square meters of mountain forest, to the city government as a site for the temporary storage of waste. Thanks to his decision, the decontamination work affecting the ten households in his district has been moving forward.

“Some people must make sacrifices,” Mr. Sato murmured, as if seeking to convince himself. “Without that, no progress can be made.” The word “sacrifice,” though, is too grave a word to utter.

(Originally published on December 7, 2011)