Fukushima and Hiroshima: Collected expertise and wholehearted support

Jan. 12, 2012

As an A-bombed city, Hiroshima continues to stand by disaster area

by Seiji Shitakubo and Yo Kono, Staff Writers

More than 100,000 people were unable to spend the New Year’s holiday at home. Residents of Fukushima Prefecture and others are still suffering since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant released radioactive materials that are invisible and whose effects are as yet unclear. People throughout Japan offered their support, and many people from Hiroshima rushed to Fukushima to offer assistance. They included doctors with years of experience treating survivors of the atomic bombing as well as scientists, police officers and volunteers. In this feature the Chugoku Shimbun looks back at the extensive goodwill that has been shown to Fukushima and considers the problems in providing continued support from Hiroshima.

Doctors and experts from Hiroshima dispel anxiety with lectures, medical exams

In late November Kenji Kamiya, 61, director of Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM), spoke to residents at a temporary housing unit in the suburbs of Fukushima City. “We will safeguard your health no matter what it takes,” he said. Dr. Kamiya continues to give lectures and provide health examinations to evacuees.

Fukushima residents have high hopes that Hiroshima’s experiences will prove useful. “I’m determined to put them to use to ease people’s anxiety,” Dr. Kamiya said. He has visited about 30 locations in Fukushima Prefecture since April, and about 10,000 people have heard him speak. “Parents’ were more concerned about their children’s health than I had imagined,” he said.

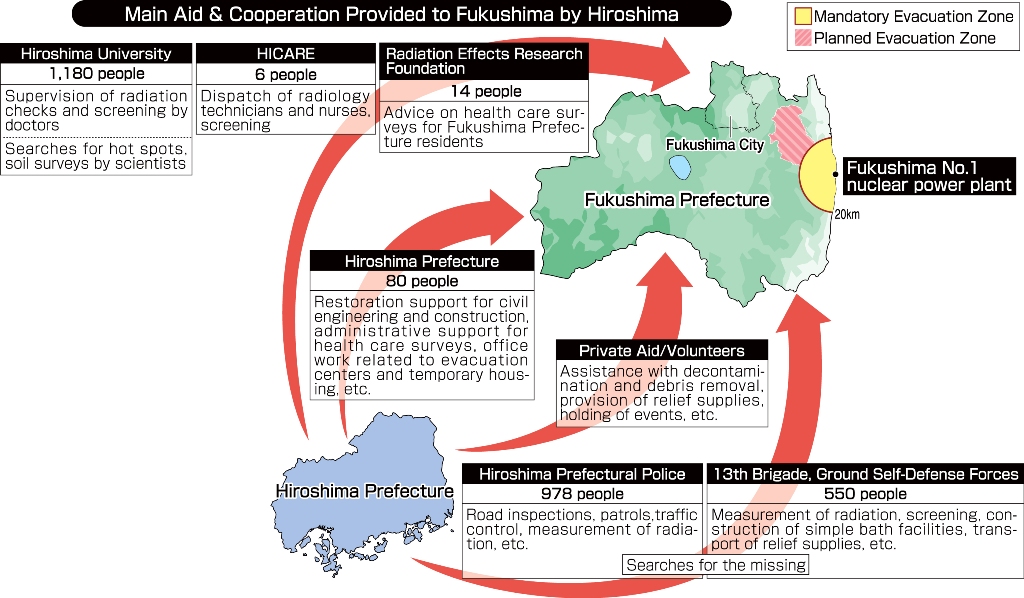

On March 12, the day after the disaster, Hiroshima University set up an Emergency Radiation Exposure Task Force. Dr. Kamiya assumed the post of chairman and led the medical team. That same day seven people, including doctors, were dispatched to Fukushima, and by the end of 2011 a total of about 1,100 people had been sent there. Dr. Kamiya, who is now serving as vice president of Fukushima Medical University also, has made more than 50 trips to Fukushima.

Apart from the RIRBM, the Radiation Effects Research Foundation sent Kazunori Kodama, 64, a chief scientist, and other foundation personnel to Fukushima. They continued to offer advice on a health care survey of the prefecture’s 2 million residents.

Not only doctors have traveled to Fukushima. Masaharu Hoshi, 64, a professor of physics at Hiroshima University’s RIRBM, went to Fukushima immediately after the accident. He measured radiation levels in the town of Iitate and discovered that there were a number of hot spots where levels were high – as high as that of the black rain that fell on Hiroshima immediately after the atomic bombing. Prof. Hoshi told officials that residents of those areas needed to be evacuated immediately.

The Hiroshima International Council for the Health Care of the Radiation-exposed, which consists of medical institutions in Hiroshima Prefecture, sent a group of six people, including radiology technicians, to Fukushima five days after the accident at the nuclear power plant. They screened evacuees for radioactive materials on their bodies and clothing.

The one-year anniversary of the accident is approaching. Shinichi Kikuchi, 65, president of Fukushima Medical University, has said that expertise from around the world must be collected in order to safeguard the health of the residents of Fukushima Prefecture. As if in response to his appeal, Dr. Kamiya said, “It is the mission of Hiroshima to stand by Fukushima.”

Kiyoshi Shizuma, professor, Graduate School of Engineering, Hiroshima University, leads effort to measure radiation, decontaminate

Kiyoshi Shizuma, 62, a professor of nuclear physics at Hiroshima University’s Graduate School of Engineering, travels to residences and businesses in Minamisoma, about 25 km north of the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant and uses a radiation counter to search for hidden hot spots where the level of radiation is high.

At 0.4 microsieverts per hour, the level of radiation in the center of Minamisoma is relatively low. But unexpected hot spots have been found in various areas such as spots in which rainwater is likely to collect. “In order to dispel residents’ anxiety, radiation in the surrounding area must be measured very precisely,” he said. A map that shows radiation levels within 1 square km was prepared based on the results of surveys conducted by the city and the central government, but it is inadequate, he said.

Prof. Shizuma is carrying out his work as a member of an environmental survey team set up by Hiroshima University. He has been to Minamisoma three times since September. During those visits he has investigated the radioactive contamination of residences, farmland, wells and other facilities and conveyed all of his findings to local residents.

For the past 27 years Prof. Shizuma has been studying the residual radiation from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, measuring the tiny amounts of radioactive materials remaining at the A-bomb Dome, the Motoyasu Bridge and other spots.

Since the accident at the nuclear power plant, about 50 samples have been brought to the professor by people hoping to take advantage of his skills. The samples included the urine of 15 residents of Fukushima Prefecture, the breast milk of mothers in Tokyo and Hiroshima, and soil from Iitate in Fukushima. “Residents want accurate figures,” he said. He did not turn anyone down and tested all the samples at no charge.

From his surveys in Fukushima Prof. Shizuma found that radioactive materials had collected in the mud in irrigation canals. Radioactive cesium in the amount of 27,000 becquerels per kilogram was detected in weeds in the mud. This was about five times the amount found in the surrounding soil. He advised residents in the area to remove the mud.

No progress has been made on the establishment of a temporary site in Fukushima for the storage of contaminated soil, and a full-scale decontamination effort has yet to begin. “Decontamination of hot spots in the immediate area should be given priority over surface decontamination,” Prof. Shizuma said. He will continue his efforts to locate nearby hot spots in Fukushima this year.

Problems: Outlook for compensation unclear, urgent need for cooperation on training of personnel

The effort to offer continued support to Fukushima faces problems such as securing funds and training personnel.

After the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, Hiroshima University sent a total of about 1,100 doctors, nurses and other personnel to the area at a cost of approximately 64 million. Hiroshima Prefecture spent 140 million on providing accommodations for evacuees, for the dispatch of medical teams, and for other projects. The prefecture also spent about 1 million to screen Fukushima residents who had evacuated to Hiroshima for internal exposure to radiation using whole-body counters.

According to Hiroshima University’s Financial and General Affairs Office, these costs will not be covered by the central government, so the university plans to bill the Tokyo Electric Power Company, but it is uncertain whether or not the entire amount can be recovered. The central government will reportedly cover most of the prefecture’s share in accordance with the provisions of the Disaster Relief Act.

Training of personnel is also a problem. For example, all of the examinations using a whole body counter conducted in Hiroshima were carried out by Yoshio Hosoi, 52, of Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine because specialized know-how is required in order to make precise measurements. And Prof. Masaharu Hoshi, also of the institute, who conducted measurements of radiation in Fukushima, will retire at the end of March. So there is an urgent need to train the next generation of personnel.

In April of this year Hiroshima University will hold a seminar for graduate students on “Recovery from the Radiation Disaster” with the intention of making a serious effort to train experts who can protect lives and the environment from nuclear disasters.

Hiroshima University is also engaged in talks with Fukushima University and Fukushima Medical University to establish a center for research on medical, environmental and other issues. Organized cooperation with local government and research institutions in Fukushima is also essential to ensure continued support.

Groups, individuals put their skills to use

Peacebuilders, a non-profit organization based in Hiroshima, sent a total of about 20 people to Fukushima, where members ran a day care service in Minamisoma, a city located within 30 km of the nuclear power plant. The service compensated for the loss of seven nursery schools that were closed in the aftermath of the disaster. About 100 members of the Volunteer Work Corps for Fukushima, which is made up of former nuclear power industry workers, decontaminated fishing boats and residences.

Shizuto Yasusaka, 68, who operates a bonesetter’s clinic in Higashi Hiroshima, volunteered his services as a private individual. “I wanted to ease the fatigue of people who were forced to live as evacuees for an extended period,” he said. Mr. Yasusaka provided acupuncture and moxibustion treatments to about 300 people who complained of pain in their shoulders, back or other areas.

Established in March of last year, Volunteer Hiroshima comprises 10 organizations, including non-profits. The group made numerous shipments of everyday goods such as chopsticks and bowls for evacuees who fled their homes with nothing but the clothes on their backs. In December three students from Hiroshima Shudo University sent futsal goals and other equipment to a youth soccer club in Minamisoma.

Since September the Hiroshima City Council of Social Welfare has dispatched a total of 95 volunteers to Minamisoma. Kumi Nakamoto, 43, a homemaker and the daughter of an atomic bomb survivor, put her 10 years of experience with handicrafts to use teaching people to knit. “Talking as they knitted, the evacuees became friends with each other. Hiroshima must not forget Fukushima,” she said, determined to etch this into her mind.

Masako Okamoto, member of the Volunteer Work Corps for Fukushima

Atomic bomb experience: Sense of mission to assist with recovery

The Volunteer Work Corps for Fukushima, a citizens’ group from Hiroshima, has been cooperating in the decontamination effort throughout Fukushima Prefecture. Among the group’s members is Masako Okamoto, 71, an atomic bomb survivor. “I felt that supporting Fukushima was my mission,” she said. In October she went to Minamisoma and assisted with the decontamination of fishing boats.

The city is located approximately 30 km from the nuclear power plant. Ms. Okamoto removed contaminated fishing nets and baskets from the boats. Other members of the corps scrubbed the decks with brushes. After the work was completed the amount of radioactive materials was one fourth what it had been.

On the day of the atomic bombing in 1945, Ms. Okamoto was in Nishi Ward, 4 km from the hypocenter. She was also exposed to the black rain and has suffered from thyroid disease. When asked why she went to Fukushima despite her ill health, she said, “Hiroshima got back on its feet with support from all over Japan. Now we need to return the favor.”

Kimio Sato, 61, the owner of one of the boats that was decontaminated by the group, told Ms. Okamato he would give fishing another try. Ms. Okamoto plans to continue her activities in Fukushima. “I want to see the evacuees looking happy again,” she said.

Hiroshima Prefectural Police, Ground Self-Defense Forces, local governments

Inspections and patrols

Construction of temporary bath facilities

Assistance with election

A support unit from the Hiroshima Prefectural Police left for Fukushima on the day of the disaster. A total of 978 people have been sent to the disaster area on 31 occasions. The police personnel entered the no-entry zone within 20 km of the nuclear power plant where they conducted inspections and carried out security patrols.

Sgt. Fumiko Numata, 31, of the department’s riot police, and Officer Shiori Fujikawa, 25, asked to be sent to Fukushima. There they patrolled temporary housing facilities, reminding residents to lock their doors and listened to their concerns. Inspector Hideki Yamaguchi, 49, of the department’s security division, conducted patrols of the area surrounding the nuclear power plant on four occasions and worked in the disaster area during the New Year holiday season.

The 13th Brigade of the Ground Self-Defense Forces, which is based in Hiroshima Prefecture, sent approximately 550 members to the disaster area. They searched for the missing and constructed temporary bath facilities for evacuees.

Hiroshima Prefecture dispatched 80 employees to Fukushima to assist with matters such as civil engineering and construction. Atsuko Saito, 57, a prefectural health promotion officer, was involved in conducting a health care survey of all residents of Fukushima Prefecture and prepared a leaflet explaining how to fill out the survey form. The City of Hiroshima has also sent 115 employees to Fukushima.

Fukushima Prefecture’s unified local election was postponed from April to November. The election boards of six cities in Hiroshima Prefecture – Fukuyama, Onomichi, Higashi Hiroshima, Kure, Hatsukaichi and Miyoshi – sent nine employees to Fukushima, and they provided administrative support to the town of Namie.

At the direction of the central government all of the town’s 21,000 residents evacuated to other areas. On the day of the election four polling places were set up in the region where there had been many mass evacuations. Kazunari Umoto, 57, a member of the election board in Fukuyama, said, “I’m glad the election went off without any problems.”

First Sgt. Norio Sawada, Chemical Protection Squadron, Ground Self-Defense Forces

Tense assignment within 20 km of nuclear power plant

Master Sgt. Koji Murata, Infantry Regiment

Recalled father’s encouragement while conducting searches

The Chemical Protection Squadron of the 13th Brigade of the Ground Self-Defense Forces worked within 20 km of the nuclear power plant. Recalling their operation, First Sgt. Norio Sawada, 42, said that although there are 30 members in the squadron, they were tense while carrying out their assignment because it was their first time to deal with radiation.

They put on protective clothing and masks and entered the area in special vehicles. For about three months Sgt. Sawada monitored the area around the nuclear power plant and participated in the decontamination effort.

Along the coast in eastern Fukushima Prefecture about 230 members of the brigade’s 46th Infantry Regiment searched for the missing and recovered 85 bodies.

Master Sgt. Koji Murata, 50, who participated in the effort, said that before he departed his ailing father sent him off saying, “Take care of yourself and do your best.” His father died while he was away. “It was my assignment. I’m sure my father understood,” he said.

Banners saying thanks to the members of the Self-defense Forces and police can be seen throughout the disaster area. “Next time I want to go to Fukushima not on assignment but to visit the rebuilt area,” said Sgt. Murata.

(Originally published on January 3, 2012)