Fukushima and Hiroshima: Unending battle with radiation

Mar. 26, 2012

One year after the accident at the nuclear power plant

50 residents of the Hamadori region today

by Seiji Shitakubo, Yoko Yamamoto, Kei Kinugawa and Yo Kono, Staff Writers

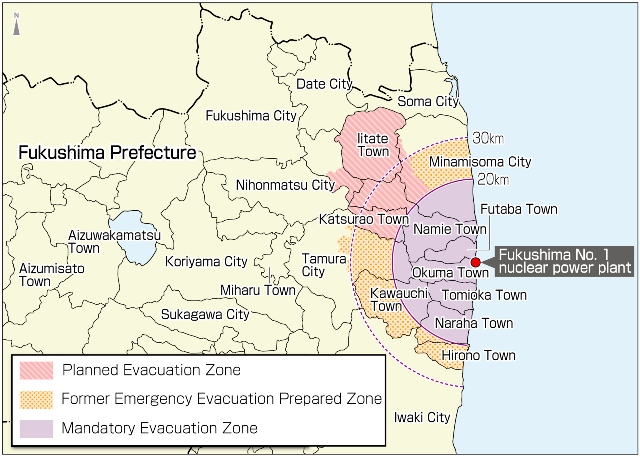

A year has passed since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The invisible, odorless radiation is still preventing about 160,000 residents of Fukushima Prefecture from returning to their homes. They wonder when they will be able to return home and if their battle with radiation will ever end. Many of them are painfully homesick. The future is uncertain, and they worry that their ties to their communities will be cut. Spring will soon be here. The Chugoku Shimbun followed up on the lives of the 50 residents of the Hamadori region today.

Life as evacuees

Delayed decontamination: Return home or relocate?

After the accident the population of Fukushima Prefecture declined by more than 40,000, falling below 2 million for the first time in 33 years.

“It was snowing that day too,” said Tadayoshi Sato, 67, gazing at the large bracken farm in front of his home as he shoveled snow. The radioactive fallout resulting from the hydrogen explosion at the nuclear power plant peaked on March 15 last year.

The town of Iitate has a population of about 6,000. The Maeda area where Mr. Sato lives has just under 60 households and was the first community to be developed. The residents formed the first agricultural cooperative in Iitate and then shifted to the cultivation of high-value-added rice. About five years ago they opened a bracken farm for tourists on pasture land that had lain idle, and they had begun to meet people from the city who visited there.

Even Mr. Sato, who has been a leader in his community, can not decide whether to return home or relocate. Their prolonged life as evacuees is forcing the residents to make a difficult decision. Iitate officials have called on all residents to return, and Mr. Sato said he understands that sentiment. “But under these circumstances I can’t ask everyone to do the same thing,” he said, occasionally fighting back tears.

The younger generation has begun to build new lives in the cities and towns to which they have evacuated, finding jobs and entering school. Farming, which has been carried out by those in their 60s, will collapse if there is a hiatus of even a few years. Life in temporary housing is sapping the vitality of the elderly. And it seems unlikely that decontamination, their major prerequisite for returning, will proceed as planned.

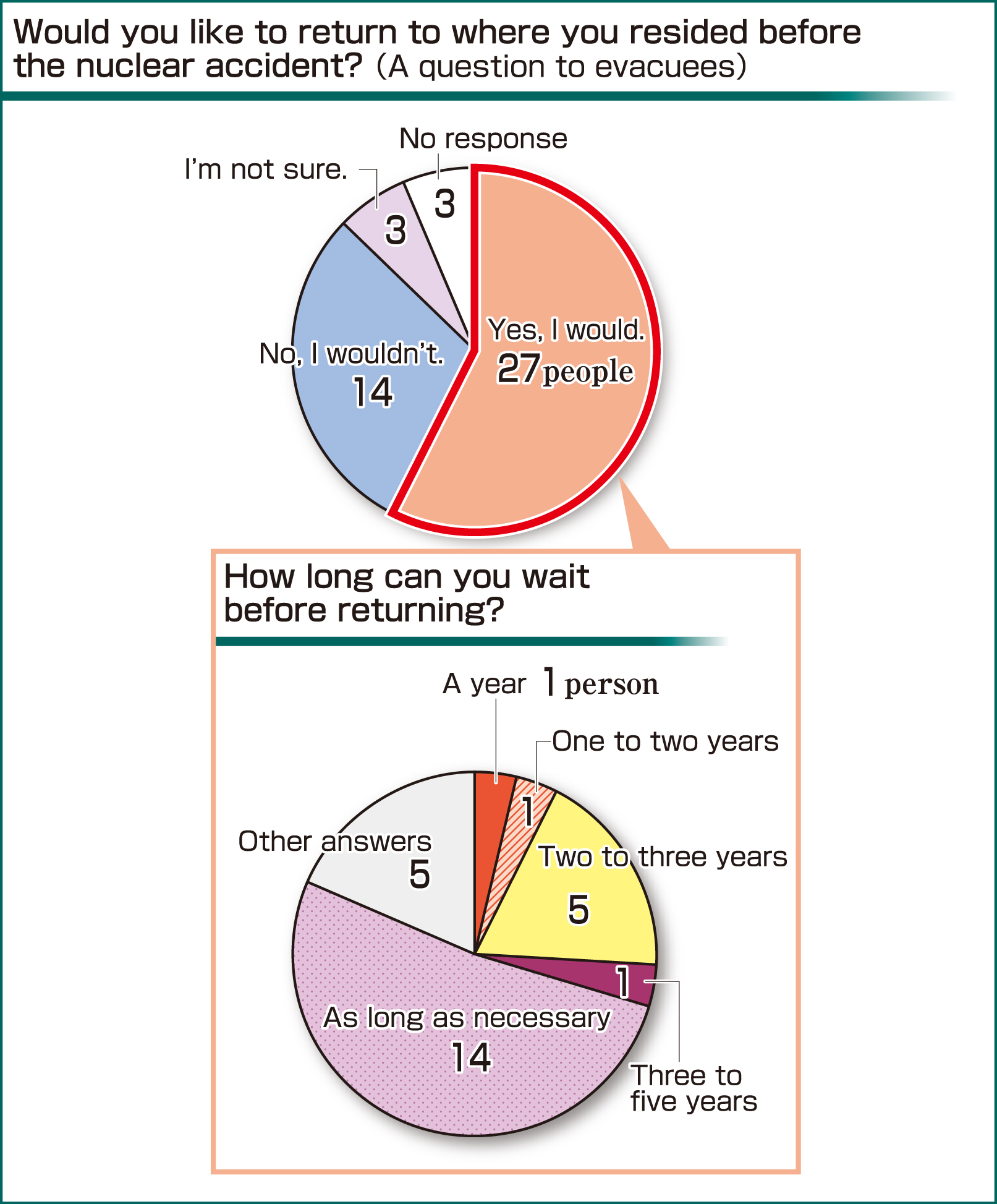

In reply to our latest survey, 27 people said they would like to return to their hometowns. Of these, 60 percent cited reasons such as the graves of several generations of ancestors, land that had been in their family for generations or their attachment to the town.

Fourteen people said they would not return home, an increase of five from the nine who said so in our previous survey last September. Slightly less than 90 percent cited the difficulty of decontamination. These results indicate that the delay in decontamination and other factors, including the lack of progress on finding interim storage facilities for radioactive debris, are causing the residents to retreat from their original intention to return home.

At the end of last year the central government told local residents that it planned to redraw the evacuation zone into three zones. More and more local governments began to talk about the concept of establishing “temporary towns” in another city to serve as new bases for their communities.

Tomiko Nakamura, 60, head of the women’s society in Futaba, said “It’s too late. When will the ‘temporary town’ be ready?” Futaba is the only town whose administrative office has evacuated outside Fukushima Prefecture as a group. The town officials predict that the redrawing of the evacuation zone will result in the majority of the areas in Futaba being classified as “no-return” and “restricted-residence” zones. In that case, prolonged life as evacuees will be unavoidable.

Last October Ms. Nakamura moved from a high school in the city of Kazo in Saitama Prefecture, where the town had located its official functions, to an apartment complex for government employees in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture. She and other citizen volunteers selected the housing themselves.

With the town’s failure to set out a path for the future, Ms. Nakamura and other residents searched on their own for vacant housing for central government employees and finalized negotiations with the government. More than 150 households from Futaba have started new lives there. They are also preparing to set up a self-government association.

“This next year will be tough,” Mr. Sato of Iitate said. “This year will make it or break it.” The residents of his community plan to get together soon to discuss the future.

Health concerns

60 percent say internal exposure to radiation “scary”

Chihiro Suzuki, 18, a high school senior, evacuated to the city of Iwaki from Namie. She is concerned about the fact that immediately after the accident she was evacuated to a “hot spot” in which the radiation level was high.

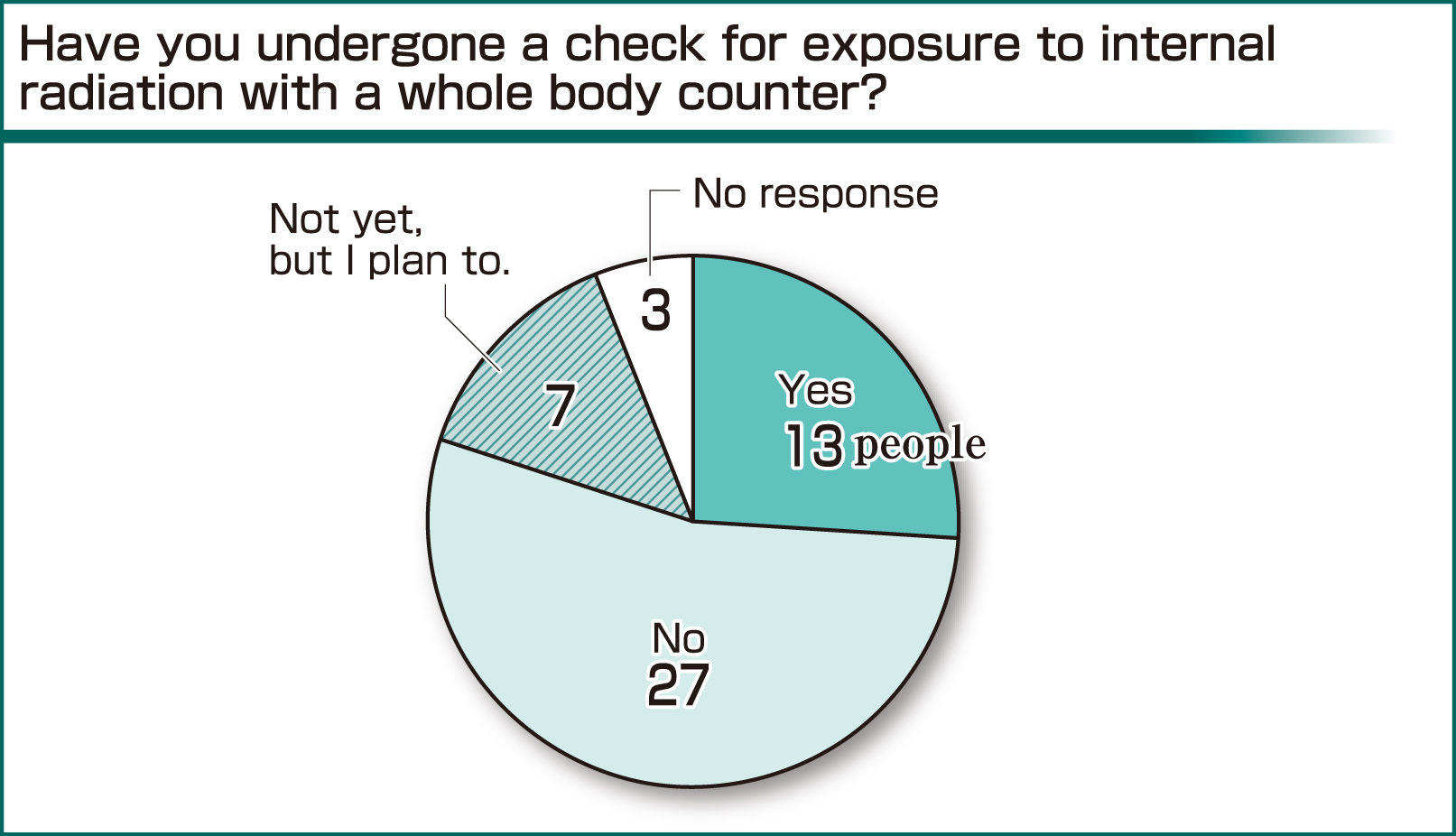

She underwent a check for internal exposure to radiation using a whole body counter (WBC). The results indicated her exposure was “below measurable limits,” and her thyroid test results were normal. But she is still concerned.

“The government, Tokyo Electric Power Company, the doctors – I don’t think anybody really knows the actual effects of radiation. I want the government to continue to conduct tests on a regular basis,” said Ms. Suzuki, who wants to have healthy children someday.

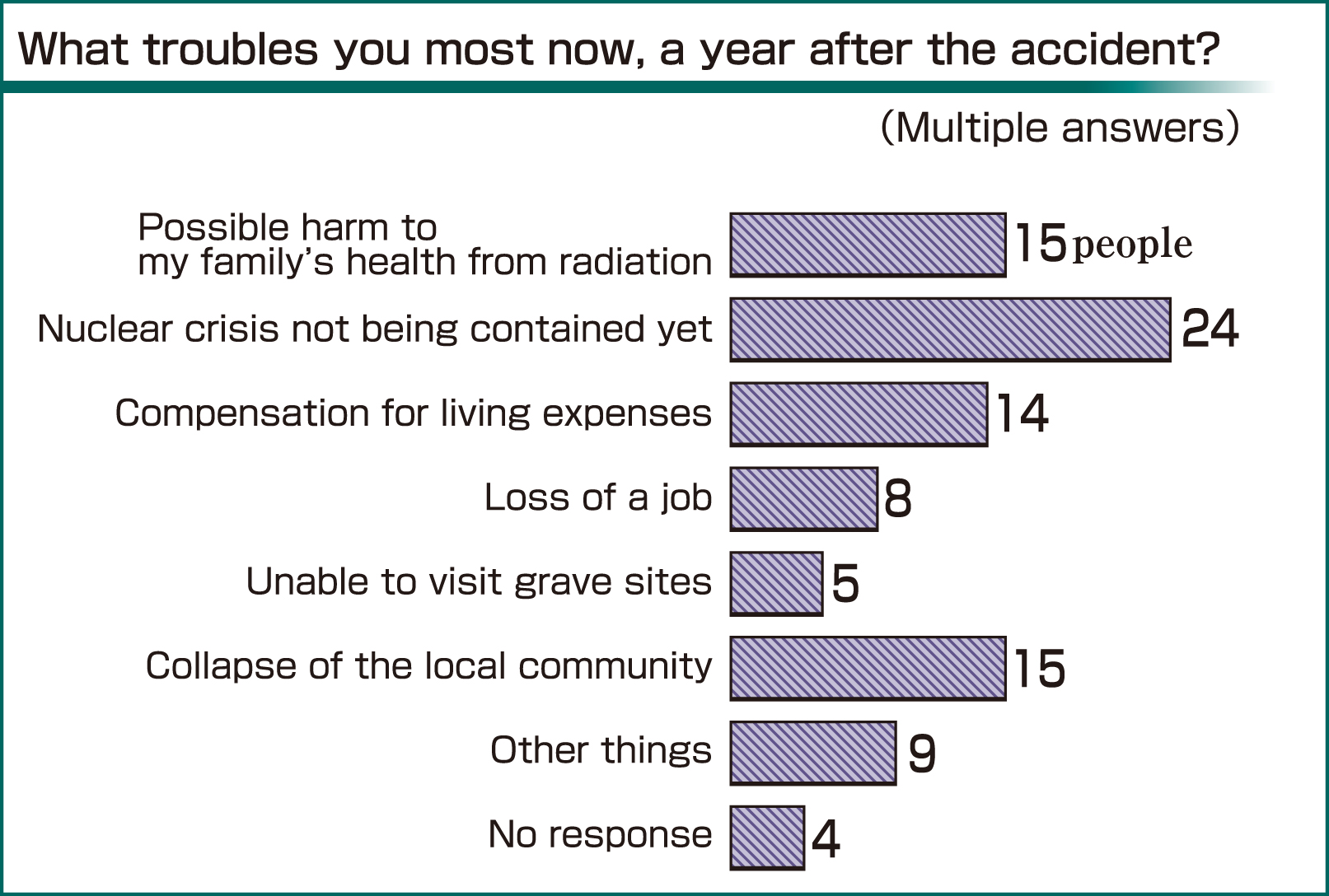

One year ago none of the victims imagined that they would ever be exposed to radiation. In our survey, well over half of the respondents said that they had detected changes in their health since the accident at the nuclear power plant. They are deeply concerned about their health in the future, and 60 percent of them said internal exposure to radiation was “scary.”

The number of those who had undergone tests for internal exposure to radiation using a WBC increased by five from last September. For several months as a rule WBC tests for residents were not carried out, so this is an improvement. But 21 of the respondents to our survey said they had been unable to have a test done although they wanted one.

Meanwhile only three of those who underwent a test said they felt reassured afterwards. Futaba resident Akemi Obata, 44, an employee of an agricultural cooperative, said she was told there was no problem. “But my exposure wasn’t zero, so that made me even more worried,” she said.

The effect of radiation on health is also a factor that influences people’s decisions as to whether or not to return to their hometowns. Last November Namie conducted a survey of all residents of high school age or older. About half of the respondents said their criterion for returning was a level of radiation equal to that prior to the disaster. Only 20 percent selected the central government’s target level of 1 millisievert per year following decontamination.

Aya Kikuchi, 17, a second-year high school student, also evacuated to Nihonmatsu from Namie. Just before the first anniversary of the accident she said to her parents, “Our neighbors were so kind. I really want to live in our house in Namie.”

But her father, Noboru, 42, has mixed feelings. He wants to fulfill her wish, but he wonders about the effects of radiation. “I want to decide on a hometown that I can confidently tell them to return to as soon I can,” he said. He continues to be concerned about his children.

Jobs lost

Uncertain prospects for the self-employed

Seiichi Shiga, 57, operated a restaurant in Namie, which is inside the no-entry zone. Waving a frying pan that he brought from his restaurant to his temporary housing, he said, “Cooking suits me best.” Before the accident he ran a restaurant that specialized in pork cutlet dishes for 30 years.

Of the 50 people we surveyed, 16 lost their jobs as a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant. This represents about 40 percent of the 38 who are left after civil servants, housewives and junior high and high school students are excluded. Those who were self-employed and who worked in agriculture, forestry and fishing were hit particularly hard. Because they had made their living with land or buildings they had invested their own money in, they face great hurdles in restarting their businesses or finding other employment.

“It takes guts to open a new restaurant when I’m still in debt for the old one,” Mr. Shiga said. “The government should provide compensation that will give us a vision for the future.” He hopes to be able to reopen his restaurant. In the meantime he has done various jobs such as helping with repair work at a school and working as a cook at a “recovery support dining hall” that was open for a limited time in Koriyama. He feels he will be able to make a decision after the upcoming announcement of the redrawing of the evacuation zones by the government.

The radioactive contamination robbed farmers of their unspoiled fields and fishermen of the sea.

Last May, when we first interviewed Kenichi Takano, 60, who raised Japanese cattle in Iitate, he was hoping to be able to raise cattle again if the level of radiation went down. But with the delay in decontamination and persistent harmful rumors he has begun to reconsider. “Even if the amount of radiation is low, I wonder if people will be willing to buy vegetables and cattle produced in Iitate,” he said.

Koji Suzuki, 59, a commercial fisherman from Namie said with a sigh, “The effects of the radioactive material will probably last for the next 10 or 20 years. My home port is 6 km from the nuclear power plant. I wonder if anyone will buy my fish.”

Key to rebuilding

Learn what to do next from Hiroshima, Nagasaki

In late February Kenta Sato, 30, of Iitate, visited the Ukrainian National Chernobyl Museum. He wrote in the museum’s guest book: “What can I do? I must start by learning.”

For about 10 days he traveled around Belarus and other areas that were contaminated by radiation as a result of the 1986 accident at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl. He wanted to assess whether Fukushima could really recover and whether or not he should leave his hometown.

Iitate, which lies about 45 km from the nuclear power plant, was heavily contaminated by radiation over a wide area. Amid conflicting information from the central government and experts, Mr. Sato looked to Hiroshima.

Upon the advice of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Kazushi Kaneko, after the accident at the nuclear power plant Mr. Sato began to keep detailed records of his activities in a notebook. He also asked Nanao Kamada, a medical doctor and professor emeritus at Hiroshima University, about ways to prevent internal exposure to radiation.

In Belarus members of the local community have set up a center to measure radioactive materials and to share information. There Mr. Sato learned about how to live while facing the threat of radiation. “I formed ties with people in both Hiroshima and Belarus,” Mr. Sato said. “I’d like to become a conduit for information for Fukushima.”

In this survey as well many respondents mentioned their thoughts about Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They said things such as “I want Fukushima to recover just as Hiroshima and Nagasaki did” and “I would like to hear from people about their lives after the atomic bombings.” Kenichi Yamazaki, 66, a resident of Minamisoma, who had called attention to the dangers of nuclear power over the years, summed up the trend toward the peaceful use of atomic energy after the war. “Japan learned nothing from Hiroshima,” he said.

Akemi Obata, 44, said she was shocked when she heard some of the stories of the atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima. Her request of them is this: “Please help us. Show us how to be brave and tell us what we can expect in the future.”

1. Residence at time of accident (current living situation)

2. Occupation, title

3. Present circumstances and comment

Keisuke Oka, 32

1. Minamisoma (living at home)

2. Part-time worker

3. The central government lifted the ban on entry to the emergency evacuation zone, but only half the residents have come back to his community. “I’m still very distrustful of the government,” he said. He is working on debris removal as a temporary employee of the local land improvement district. “The debris is just piled up at a temporary yard. I don’t sense reconstruction.”

Ayako Kobayashi, 51

1. Minamisoma (living at home)

2. Housewife

3. The radiation in the soil under her rain gutters measured over 100 microsieverts per hour, so she had the topsoil removed from the entire yard. But it seems unlikely that she will be able to live with her two daughters, who are in their 20s. “Our family is scattered, and I’m mentally exhausted,” she said. She is angered by what she believes to be the government’s groundless declaration that the accident at the nuclear power plant has been brought under control.

Tomoko Shineha, 27

1. Minamisoma (moved to Soma in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Housewife

3. She said she feels mentally unstable. Her husband is a doctor, and in late March they will move to Yokohama on account of his work. When she thinks that she might be stuck with the image of “a person from Fukushima,” she feels even more worried. “After the war, the people of Hiroshima went through a lot of hardships on account of the atomic bombing. Now we are going to bear the burden of radiation exposure.”

Tatsuya Suzuki, 30

1. Minamisoma (evacuated within the city)

2. Thermal power plant worker

3. In order to avoid exposure to radiation, there are still restrictions on how long children can play in the schoolyard at the elementary school attended by his 11-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son. In spite of that, the central government is planning to redraw the evacuation zones, but he has doubts about this measure. “My biggest concern is the effect on my children,” he said. “I want the government to exercise caution when making a decision.”

Shoichi Suzuki, 57

1. Minamisoma (living at home)

2. Lumber business, member of city council

3. The emergency evacuation zone designation has been lifted in one area of the city, but residents have been slow to return. Sales at his lumber store are about one third of what they were the previous year. The major challenge for the city is decontamination. “Even if the amount of radiation is cut in half I wonder if the residents will return,” he said. He feels setting a course toward recovery will be difficult.

Kenichi Yamazaki, 66

1. Minamisoma (evacuated to Kawasaki in Kanagawa Prefecture)

2. Former high school teacher

3. Full-scale decontamination has not yet gotten underway in Minamisoma. He and four other evacuees visited Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) last December and the prime minister’s office in January and asked that they move forward with the decontamination work. “Instead of leaving the decontamination up to the government, TEPCO should assume responsibility for the accident at the nuclear power plant and take the lead in the decontamination work,” Mr. Yamazaki said.

Takumi Aizawa, 40

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Prefectural government employee

3. He and other volunteers have asked the central and local governments to “assess the impact of radiation on health from the residents’ point of view.” He feels that internal exposure to radiation is still being underestimated and the government is trying to brush the residents off. He said he would like Hiroshima to “support each individual’s path to recovery.”

Mari Kobayashi, 47

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. NPO employee

3. She goes back to Iitate once a week to look after her chickens and to take care of her house. She feels that the flood of information on the effects of radiation is “causing rifts among residents.” As the evacuees’ fatigue reaches its limit, “mental health care is really needed,” she said.

Kenta Sato, 30

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Vice chair of the local junior chamber of commerce

3. He is still angry about the remark by an expert who visited Iitate just after the accident and said, “Even [total exposure of] 100 millisieverts doesn’t pose a health problem.” He has been asked to give lectures and travels to various areas and talks about the distress of the people of Iitate and the situation there. “I want to tell people about the situation directly and connect with them,” he said. He said he is doing this for the children of the future.

Tadayoshi Sato, 67

1. Iitate (evacuated to Date in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Farmer

3. In January he set up a stand at temporary housing in the city of Fukushima to sell agricultural products produced by Iitate residents. They have rented farm land near their temporary housing and bring the products they grow there to the stand to be sold. “Farming is everyone’s reason for living,” he said. “Bold measures, such as promoting hydroponic farming, are needed [for the full-scale recovery of agriculture].”

Hachiro Sato, 60

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Farmer, member of town council

3. In order to prevent internal exposure to radiation, he is careful about what he eats. He started taking more interest in Hiroshima as the result of activities by the local youth organization in Iitate. “Human beings shouldn’t mess with nuclear energy, which they can’t control,” he said. He said he is angry at the central government, which insists on Japan’s export of nuclear power plant technology.

Mikiko Sato, 60

1. Iitate (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Chair, village women’s society

3. She serves as manager of the temporary housing. “The longer we have to live as evacuees the more stressful it will be,” she said. “I’d at least like to be able to spend time with other evacuees so I can live cheerfully now.” Recently her pulse sometimes races, so she underwent a cardiac examination. “I want the government to put a greater priority on people’s lives than on the economy,” she said.

Kenichi Takano, 60

1. Iitate (evacuated to Soma)

2. Company employee

3. He closed the livestock business that his 34-year-old son was supposed to take over. He planned to return to Iitate and resume raising cattle after a few years, but it was too difficult. He is considering raising flowers near his temporary housing using hydroponics. “If we’re able to go back to Iitate, I’ll move the equipment there and let my son take over,” he said.

Yoshimune Hasegawa, 32

1. Iitate (evacuated to Yamagata Prefecture)

2. Dairy farmer

3. He got a job and continues to work in the dairy industry. In a survey of residents of his community he said he would not return to Iitate. “It won’t go back to the way it was during my lifetime,” he said. The cattle shed and other facilities at his house will stay the way they are. “I can’t sell the property,” he said. “Even now, a year after the accident, my life is still unsettled.”

Masako Kamata, 61

1. Katsurao (evacuated to Miharu in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Pig farmer

3. Even if the evacuation zones are redrawn, she has no intention of returning to Katsurao. “Unless radioactive materials are completely gone, I can’t even eat the vegetables I grow without worrying,” she said. She would like the government to develop forest land or other property it owns away from the nuclear power plant and build a housing development where people can live for a long time.

Fumio Matsumoto, 59

1. Katsurao (evacuated to Miharu)

2. Former construction worker

3. He lives with his 89-year-old mother in temporary housing. He couldn’t go to work because he needed to care for her, so at the end of January he was fired. Their home is inside the no-entry zone. He said the time he was allowed to return home temporarily was the happiest moment of the past year. “I’ll keep waiting for the day when decontamination lowers the level of radiation enough for me to return home.”

Aya Kikuchi, 17

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. High school student

3. She joined the volleyball team at her new high school in Nihonmatsu. Under the rules she is not allowed to play in tournaments, but, she said, “I’m happy about making new friends.” Nevertheless she can’t help feeling homesick. “Namie is still the best,” she said. She recalls the faces of neighbors who were kind to her.

Hidezo Sato, 67

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Seed and plant business

3. He moved inland from the temperate coastal area. This winter the low temperature went down to 10 degrees below freezing. The water in his temporary housing couldn’t be used for five days in a row. “The climate here doesn’t suit those of us from the coast,” he said. “When a decision is to be made about where we’re going to move, I want the residents’ opinions to be heard first.”

Seiichi Shiga, 57

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Restaurant management

3. He is distressed by other residents of Fukushima Prefecture living further from the nuclear power plant who make snide remarks “You got compensation so what are you complaining about?” or “You didn’t really suffer so much damage.” “I want to set up a place where people can go to complain freely,” he said. He is thinking about operating a street vendor’s stall that he will take around to the temporary housing units.

Chihiro Suzuki, 18

1. Namie (evacuated to Iwaki in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. High school student

3. She was living with her grandmother, but they evacuated to separate locations. Starting in April she will attend college in Sendai. “I’m worried about my grandmother, so I don’t want to leave the Tohoku area,” she said. She also worries that aftershocks may cause another explosion at the nuclear power plant. She feels the central government should make health care for children free and safeguard their health.

Koji Suzuki, 59

1. Namie (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Fishing industry

3. He and his brother engaged in commercial fishing at a location 6 km from the nuclear power plant. Their boat’s berth is in the no-entry zone. “The engine is rusting, and I don’t think I’ll ever be able to fish again,” he said. His old friends have lent their support while he lives as an evacuee. Some of them have given him appliances. “I feel grateful for people’s warm-heartedness,” he said.

Shunji Sekine, 69

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Doctor

3. He is still angry that the central government delayed releasing the results of the calculations made with the System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information (SPEEDI). “A lot of people were exposed to radiation unnecessarily,” he said. He also can’t understand the delay in starting examinations for internal exposure to radiation. “I’m thoroughly disgusted with the way the government has handled things,” he said.

Yoshihiko Monma, 32

1. Namie (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Singer/songwriter

3. He continues to travel around to evacuation centers and temporary housing giving performances. He is sometimes invited to perform in the Kanto region and other areas outside Fukushima Prefecture as well. At his performances he also talks about the situation in the area affected by the accident at the nuclear power plant. “I want to continue to tell as many people as possible about the accident at the nuclear power plant so memories of it won’t fade,” he said.

Shiro Yamada, 72

1. Namie (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Head of regional agricultural mutual relief association

3. He grew pears, a local specialty, for 20 years. Just as he switched to another variety, his trees were contaminated with radiation, so he was unable to harvest his first crop last fall. “At my age I just can’t farm anymore,” he said. When the nuclear power plant was built he worried about harm to agriculture and is filled with regret now that his worst fears have been realized.

Nao Watanabe, 15

1. Namie (evacuated to Nihonmatsu)

2. Junior high school student

3. He has been separated from his friends and teachers and is still unable to contact some of them. He wanted to do some sort of work related to nuclear energy, but the accident completely changed his mind. He is worried about internal exposure to radiation from food and other things. “I think it will be difficult to go back to my hometown to live, but I don’t want to lose it either,” he said.

Miho Inoi, 24

1. Futaba (evacuated to Saitama Prefecture)

2. Part-time elementary school teacher

3. She relocated to Saitama along with the city offices. She and her boyfriend are going to get married. “It seems like the kids from Futaba are smiling more these days. That encourages me,” she said. “The emotional scars and regret won’t go away, but I’m forming new ties. I want to move forward.”

Akemi Obata, 44

1. Futaba (evacuated to Saitama Prefecture)

2. Agricultural cooperative employee

3. She is working at a support center set up by Futaba’s agricultural cooperative in Kazo, Saitama Prefecture. She finds it very sad that people seem to be forgetting about the accident. She is encouraged when she sees her first-grader son head happily off to school. “The accident at the nuclear plant won’t really be ‘under control’ until we can live someplace with a sense of relief and feel at peace mentally.”

Yoshinori Tsuchida, 63

1. Futaba (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Retired carpenter

3. He moved from an evacuation center in Inawashiro in Fukushima Prefecture and is now living in rental housing. “The circumstances of the disaster victims have not improved,” he said. He was working at the No. 1 nuclear power plant at the time of the earthquake. “I completely swallowed the myth of safety,” he said. “I was in favor of nuclear power, but now I can’t say one way or the other.”

Tomiko Nakamura, 60

1. Futaba (evacuated to Ibaraki Prefecture)

2. Chair of town women’s society

3. She lives with her husband. Their son and his family, who had evacuated to Shizuoka Prefecture, have moved nearby. “We finally found a place where we can feel settled,” she said. The granddaughter she held protectively at the time of the earthquake will start elementary school this spring. “I want to smile more and live with an upbeat attitude,” she said.

Fumihito Hayama, 35

1. Futaba (evacuated to Saitama Prefecture)

2. Operator of iron works

3. He offers advice to evacuees at a center he set up in Tokyo. “Everyone is angry because they can’t seem to get any information,” he said. He hasn’t received any effective assistance himself, so he hasn’t repaid a loan he got from a business partner. “Compensation and support are being decided on without input from the people concerned,” he said.

Mitsuharu Yatsuda, 70

1. Futaba (evacuated to Ibaraki Prefecture)

2. Farmer

3. When he was a member of the town council he voted for expansion of the facilities at the nuclear power plant to aid the development of the community. The other day an employee of the Tokyo Electric Power Company came to the home he has been living in since evacuating. “For 30 years I was in favor of nuclear power. I feel like I’ve been betrayed,” he said. “Generations of my ancestors’ graves are there. It’s not a matter of wanting to go back. I have to go back.”

Masao Akimoto, 72

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizu Wakamatsu)

2. Manager of fishing supply store

3. As head of the town’s welfare and children’s council, he goes around to check on elderly people. He said he and many other elderly people can’t get used to apartment life. “If the evacuation order is lifted, I’ll go home immediately even if the radiation level is high,” he said.

Takeshi Ouchi, 63

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizu Wakamatsu in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Farmer

3. His home is 2 km from the nuclear power plant. The radiation level is high, and the area is expected to be designated as a no-return zone. “I don’t expect to be able to go back during my lifetime,” he said. “I have to find someplace to live soon. A year has passed, but I still can’t seem to sort out my feelings.”

Ayako Oga, 39

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizu Wakamatsu)

2. Farmer

3. She underwent a test to measure the amount of radioactive materials in her breast milk. She would like to see a law passed under which the central government would provide for the health and livelihoods of the residents of Fukushima Prefecture. “We need a law with comprehensive assistance measures that covers a lot of people. The government should refer to the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law that provides relief to the survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” she said.

Machiko Kikuchi, 60

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizu Wakamatsu)

2. Unemployed

3. “I feel like the government hasn’t heard what the evacuees have been saying for the past year,” she said. Before winter, through her town government she began asking that the central government install snow guards on the roof of the temporary housing, but it wasn’t done until mid-February. “As for redrawing the evacuation zone and the decontamination, I’d like the government to listen to residents’ opinions directly,” she said.

Makoto Sato, 64

1. Okuma (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Straw mat manufacturing

3. He questions the fact that the government announced that the accident at the nuclear power plant was “under control” despite the fact that small amounts of radioactive materials are still being released. “It won’t really be under control until the reactors are dismantled,” he said. “It will take a long time to do that, so the government should focus on building new residences.”

Shuei Shiga, 70

1. Okuma (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Head of local agricultural cooperative

3. He feels that this year will decide whether or not agriculture in the Hamadori region can recover or not. He is studying the effects of radiation on test fields that have been set up in Hirono and other areas. He plans to analyze the results and then press for planting next spring. “I want to provide as much support as I can to ensure that farmers don’t lose their motivation to grow crops,” he said.

Yoshiko Suganami, 41

1. Okuma (evacuated to Fukushima City)

2. Judicial scrivener

3. She hasn’t been able to make up her mind to open a new office, so she can’t take on any new work. She has been attending briefings conducted by the prefectural judicial scriveners’ society and other organizations on compensation to be paid by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). “There are no law offices in Futaba-gun,” she said. “TEPCO should explain the procedures for receiving compensation to the evacuees in a way they can easily understand.”

Minoru Yoshida, 64

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizu Wakamatsu)

2. Former nuclear power plant worker

3. He worked on the construction of the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant and other facilities for about 40 years. He retired at the end of March last year. “A major accident occurred, and now I feel empty wondering why the nuclear power plant was built,” he said. If he can’t return home in three years he plans to relocate outside of Fukushima Prefecture.

Nobuyuki Watanabe, 59

1. Okuma (evacuated to Aizu Wakamatsu)

2. Chairman of construction company, member of town council

3. The eight towns and villages in Futaba-gun are not in agreement as to what to do about issues such as where to build temporary storage facilities for contaminated soil. He believes the merger of these eight municipalities is necessary to speed up recovery. “We should establish a new city in an area where the level of radiation is low and create jobs and build hospitals there,” he said.

Osamu Ando, 62

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Miharu)

2. Temporary worker

3. He is carrying out weekly crime prevention patrols in Tomioka under a contract with Fukushima Prefecture. When he looks out over the land he farmed before the accident he feels an even greater attachment to his home. “Decontamination is a tough job,” he said, “but the government must see the job through until the radiation is down to the level it was before.”

Toshiro Kitamura, 67

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Sukagawa in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Participant, Japan Atomic Industrial Forum

3. He was in favor of generating electricity using nuclear power, but now he is opposed to it. He has given up on living in his contaminated house for quite some time. “Japan is a small country and earthquakes occur frequently, so it’s not suited to nuclear power,” he said. “From the standpoint of the government’s inability to cope with the accident as well, we shouldn’t use nuclear power.”

Tomoyuki Seki, 66

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Farmer, member of town council

3. On the day of the disaster he barely escaped the tsunami. He had been campaigning to end Japan’s reliance on nuclear power since before the accident. “It was beyond my ability,” he said. He wants the government to create a mechanism to keep children’s exposure to radiation below 1 millisievert per year, and he wants the reactors at all the nuclear power plants in Fukushima Prefecture to be decommissioned and dismantled.

Misao Sekine, 63

1. Tomioka (evacuated to Miharu)

2. Retired nuclear power plant worker

3. He is living alone in temporary housing. The compensation he received from Tokyo Electric Power Company covers nearly all of his living expenses. “I can’t rely on the compensation forever,” he said. He is looking for work, but it is difficult because of his age. “I want to do something for my hometown,” he said. He is looking for a job related to decontamination.

Kimio Akimoto, 64

1. Kawauchi (evacuated to Tamura in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Head of regional forestry cooperative

3. He feels that the central government’s decontamination project places priority on residences and that forests are being put on the back burner. “If the mountains are neglected, the forests will deteriorate and landslides and other disasters will be more likely to occur,” he said. “The government should seriously consider how they are going to proceed with the decontamination,” he said.

Yoshitoyo Sakuma, 29

1. Kawauchi (evacuated to Koriyama in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Company employee

3. He commutes 70 km by car from his current residence in Koriyama to his workplace in Kawauchi. In January Kawauchi became the first municipality in Futaba-gun to which residents were allowed to return, but he plans to stay in Koriyama. “Even doctors don’t really know the effects on health of radiation,” he said. “I can’t take my daughter back there.”

Chido Sakuma, 30

1. Naraha (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Buddhist priest

3. Since the accident at the nuclear power plant he has moved more than 10 times to various places including evacuation centers and the homes of relatives. He is now living in temporary housing in Iwaki. In response to our request for an interview he said, “I don’t want to talk about anything now.”

Kazuhiro Matsumoto, 42

1. Naraha (evacuated to Aizumisato in Fukushima Prefecture)

2. Company employee

3. The electrical company where he works is within 20 km of the nuclear power plant, and one year after the accident it is still shut down. “The hardest thing is that even now I can’t see where my life is going,” he said. As for Tokyo Electric Power Company, he said, “They should stop the emission of radioactive materials from the nuclear power plant and pay full compensation to local residents.”

Rie Abe, 40

1. Hirono (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Housewife

3. She was reunited with other members of her taiko group at a concert in support of recovery of the region in January. “I was thrilled to be able to perform with the group again after such a long time,” she said. In March the town moved its functions back to the original town hall. Her child’s school is expected to reopen in time for the second semester of the new school year. “I’d like to move back after assessing the decontamination situation,” she said.

Kazumasa Komatsu, 43

1. Hirono (evacuated to Iwaki)

2. Municipal employee

3. He lives with his wife and 16-year-old daughter. He is in charge of the health and welfare of the residents of Hirono. “I’m grateful to the public health nurses who rushed here from Tokyo and Shizuoka Prefecture,” he said. He is interested in the health examinations that are provided to the survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “In order to safeguard the health of the people of Fukushima Prefecture, we should learn from that system,” he said.

Keywords

Redrawing of evacuation zone

The central government plans to redraw the current evacuation zone into three zones by the end of March. Under this plan areas in which the annual dose of radiation is 20 millisieverts or less will be designated “zones being prepared for the lifting of the evacuation order.” Areas with an annual radiation dose of between 20 and 50 millisieverts will be called "restricted-residence zones," while those with radiation exceeding 50 millisieverts will be referred to as "no-return zones." The government also released a schedule showing it plans to completely decontaminate the zones being prepared for the lifting of the evacuation order and lower the radiation dose in the restricted-residence zones to 20 millisieverts or less by the end of March 2014. On the other hand, it is unclear when a full-scale decontamination effort will begin in the no-return zones.

System for the payment of compensation by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO)

The scope of the compensation will be decided on by the Dispute Reconciliation Committee for Nuclear Damage Compensation of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. As for the psychological distress of the residents who have been forced to live as evacuees for a long period, in principle, payments of 100,00 per person per month will be made for the first six months after the accident. The payments will be reduced to 50,000 per month for the period thereafter.

Compensation to small and medium-sized companies will be calculated based on their regular profit. In the case of farmers, compensation will be calculated based on the area of the land that can no longer be cultivated and its expected income. Compensation will also be paid for losses from agricultural products that had to be disposed of as a consequence of the accident. If victims can not reach an agreement in their negotiations with TEPCO, they can request mediation by the Center for Dispute Resolution for Compensating Damages from the Nuclear Power Plant Incident.

(Originally published on March 12, 2012)