Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Letters and diaries written just after the city’s destruction 1

Jul. 10, 2014

Genshin Takano, governor of Hiroshima Prefecture

Among the surviving letters and diaries on Hiroshima are letters written by Genshin Takano (1895-1969), governor of Hiroshima Prefecture at the time of the atomic bombing, and the diary of Tetsuzo Kitagawa (1907-1983), who came to Hiroshima from Tokyo two days after the bombing as a member of a Navy survey team. How did this policymaker and scientist cope with and react to the unparalleled conditions that resulted from the atomic bombing by the U.S. military on August 6, 1945? These articles follow the stories behind those historical letters and diaries as well as related materials and analyze their content.

September 7: “606 prefectural employees have died”

Genshin Takano served as vice governor of Osaka Prefecture before being appointed governor of Hiroshima Prefecture by the government on June 10, 1945. Four letters he wrote while governor survive. All of them were addressed to Kiyoshi Ikeda, governor of Osaka Prefecture. The two men had previously worked together at the Home Ministry. In a letter dated September 7, the first he wrote after the A-bombing, Mr. Takano said: “This area is in a truly terrible state as a result of the atomic bomb attack... Already 606 prefectural employees have died, and there will be a considerable number of deaths. Most of those who survived were away on business trips.”

Many prefectural employees also died as a result of acute radiation sickness. Ultimately a total of 1,131 prefectural employees died, including those who had been assigned to police and fire stations.

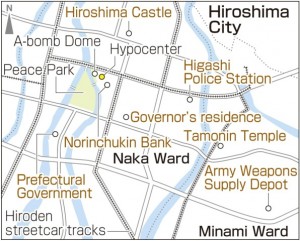

The governor escaped death because he was in Fukuyama on business on August 6. He hastily returned to Hiroshima. The city’s air defense headquarters had been moved to Tamonin Temple on Hijiyama (Minami Ward). According to the “Overview of Measures Taken in Hiroshima Immediately after the Aerial Bombing” (in the collection of the municipal archives), Mr. Takano arrived there at 6:30 p.m.

Hirokuni Dazai, manager of the Prefectural Police Department’s Special Political Police Section (later vice minister of the Ministry of Health and Welfare), described the situation at the temple in an account he contributed to Naimusho Gaishi, an unofficial history of the Home Ministry. “I was just about to say how glad I was that the governor was safe when [Officer Torayoshi] Ishihara, who was sitting next to me, said, ‘I heard that the governor’s wife is missing.’ I didn’t know what to say.”

On August 7 Mr. Takano had temporary prefectural offices set up at the Higashi Police Station in Shimoyanagi-cho (now Kanayama-cho, Naka Ward), which had escaped the fires. There he met with Field Marshal Shunroku Hata commander of the Second General Army, and they worked out relief measures. Isei Otsuka, superintendent of the Chugoku Regional Superintendency-General, which administered the five prefectures of the Chugoku Region, and Senkichi Awaya, mayor of Hiroshima, were both killed in the atomic bombing, making Gov. Takano the sole surviving local government leader.

He set up relief stations at Sen-tei (now Shukkeien Garden) and Furuta National Elementary School (located in what is now Nishi Ward), and decided on measures related to food including the distribution of canned food and vegetables for 200,000 people as well as 56 grams of dried sardines per person. He also decided that homes in neighboring rural districts should each provide two items of tableware. At the same time, he had notices posted throughout the prefecture telling citizens, “We must believe in ultimate victory.” Then, eight days later, on August 15, as governor he advised citizens of the end of the war.

The whereabouts of the governor’s wife Shinako, 40, were unknown. According to an account written later by Kisaburo Takeuchi, manager of the prefecture’s personnel and food departments, for Hiroshima Kencho Genbaku Hisaishi (Chronicle of A-bomb Damage to the Hiroshima Prefectural Government Offices), Mr. Takano first went to the burned-out governor’s residence in Shimonaka-machi (now Naka-machi, Naka Ward) on August 30. The prefectural offices had been relocated to Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda) in Fuchu-cho on the outskirts of the city.

“When he saw his burned watch and mounting for his medals, all he said was, ‘This must have been the living room.’ Standing beside him, I felt very sad,” Mr. Takeuchi wrote.

This first letter makes no reference to the death of his wife either. Rather, as the civilian responsible for air defense, the governor frankly describes his feelings of chagrin at the large number of deaths, including those of prefectural employees. “We cannot do anything for air defense… Scientific research may be the deciding factor in future wars,” Mr. Takano wrote.

A total of 2,012 people in Hiroshima Prefecture were killed when the Makurazaki Typhoon hit on September 17. The governor was subsequently ordered to take measures in preparation for the stationing of Allied troops in the prefecture. On October 11 Mr. Takano was named superintendent-general of the Metropolitan Police in Tokyo. Because the railway passenger cars were packed with returning soldiers, Mr. Takano left the city aboard an engine. He worked on public safety measures for Tokyo during a turbulent time but was forced to resign in January 1946 with the issuance of a purge directive by the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces. He subsequently became a lawyer.

“Typical of people from Aizu [Aizu-Wakamatsu, Fukushima Prefecture], my father was a man of few words,” said his son Motoaki, 87, a resident of Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture. “He didn’t talk about what he did in Hiroshima, and he didn’t leave a personal history either.”

Mr. Takano did not get an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. Shinako’s remains were never found. At the Tama Cemetery in Tokyo, Motoaki had this inscription written about his mother: “Died in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.” “I felt that the atomic bombing was unforgivable, so I had that put on there,” Motoaki said.

(Originally published on May 12, 2014)

-249x300.jpg)

-300x204.jpg)