Special Series: 60 Years of RERF, Part III [3]

Sep. 11, 2014

Hiroshima and the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission: Jeep sent to pick up survivors

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

Bitter memories of giving blood samples

One word mentioned by nearly all A-bomb survivors and family members of the dead, when talking about the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) is “jeep.” American jeeps evoked both feelings of admiration for American culture, symbolized by this compact four-wheel drive vehicle, and bitterness toward the United States, the victorious nation that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Awful memories of being compelled to give blood samples return to Mitsuko Kubo, 78. The housewife, who lives in Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture, said, “I didn’t want to get into that jeep.”

Ms. Kubo experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 16 and her exposed left arm was badly burned, except the parts that were shielded by her lunchbox and textbooks.

Two years later, an employee at the ABCC, which had just been established, came to the small newspaper company where she worked. When she was ordered to appear to give blood samples, she objected, saying, “I don’t want to give my blood.” The employee, who looked Japanese, responded in a reproachful tone in broken Japanese: “How can you say such a thing?” He added, “You could be tried and court martialed for this,” and insisted that he would return the next day to pick her up.

The next day, she went to Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital (now, Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital), where the facility was temporarily located, on her own, because she did not want to be driven there in the jeep. As her blood sample was taken, she was filled with chagrin. She explained how she felt to the interpreter, but he said, “Japan was defeated, and it can’t be helped.”

Ms. Kubo’s younger brother, who died two years ago at the age of 72, was taken to the ABCC by jeep.

He was a boy going through puberty back then, and had suffered severe burns to his face and other parts of his body in the atomic bombing. A jeep shuttled him from his school to the ABCC many times. One day, after arriving home, he said in tears, “It was so painful.” Recalling the moment, Ms. Kubo frowned and said, “I took off his shirt and found a scar around his ribs. It looked like he had been stuck with a big needle used for making tatami mats.”

“I guess it was tough for a boy of that sensitive age to be exposed to people’s curious stares,” she said. “He stopped going to school, started drinking too much, and fell into debt. He lost control of his life.”

In 1951, the ABCC moved into a newly constructed building in the Hijiyama district. Ms. Kubo confided that she often had a dream in which Hijiyama Hill is blown up by explosives.

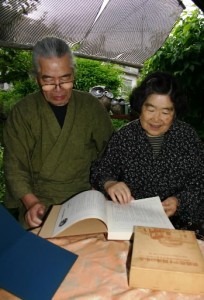

“My anger at their strong-arm approach in their research made me aware of my identity as a survivor,” Ms. Kubo said. After many years, she became able to talk about her experience in public. She joined a group of A-bomb survivors and was involved in editing memoirs. Last year she compiled her poetry and her memories into a book. The chapter about her anger toward the ABCC is titled “I Will Not Give My Blood.”

Listening to her story, Ms. Kubo’s husband Hiroyuki, 75, said, “The hibakusha [A-bomb survivors] were burned down to their hearts. You have to abandon your humanity to be able to use them as mere subjects of research.”

The ABCC, whose heavy-handed approach to its early research studies was met with criticism, called the survivors “collaborators.”

(Originally published on June 8, 2007)