Setsuko Yamagiwa, 86, Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima

Dec. 8, 2014

Handing down memories of the A-bombing and its aftermath

Worked as breadwinner while supporting younger siblings

by Takeshi Kikumoto, Staff Writer

Setsuko Yamagiwa, 86, lost her father, Masaichi, to the atomic bombing. At the time, he was 38 years old and worked for the Hiroshima prefectural government. Without her father, the family fell into poverty and the future looked bleak. At the age of 17, she had no choice but to become the breadwinner for her family. Meanwhile, she helped her mother, who was in poor health, raise her two younger sisters and one young brother.

Her father began working for the Chugoku Regional Superintendency-General, located on the grounds of the Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (today’s Hiroshima University) and other sites, in June 1945. The day before the A-bomb attack was a Sunday. Ms. Yamagiwa’s family had a happy dinner with the whole family in the village of Yahata in Hiroshima Prefecture (part of present-day Saeki Ward, Hiroshima City), to where they had evacuated earlier. It remains Ms. Yamagiwa’s last memory of her family all together.

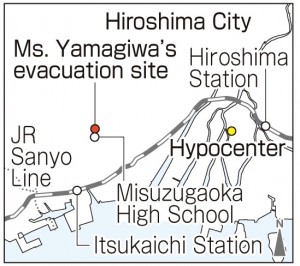

On August 6, Ms. Yamagiwa had a fever, so she stayed in bed and was absent from her work as a mobilized student at a factory in the Eba district (in today’s Naka Ward). Then she heard her mother, Masako, screaming, “The sun has split in two!” When she looked in the direction of the city center, she saw huge columns of flame rising in the sky over Hiroshima. Her father did not return that night.

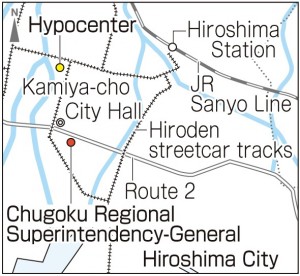

The following morning, Ms. Yamagiwa and her mother left at dawn to search for her father. They combed the area where he worked and looked for him in the Kamiya-cho district, where they heard he might have gone. The rivers and burnt land were choked with victims of the blast. The dead were in heaps inside charred streetcars. Hoping to spot her father’s distinctive trousers and lunchbox, Ms. Yamagiwa spent the next two months wandering through relief shelters and cremation sites, but was unable to find him.

In March 1946, Ms. Yamagiwa graduated from high school. With her family, she then moved to the village of Ono, in the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, where her mother had lived before she got married. There she became a substitute teacher at a local elementary school. But a year or so later, feeling awkward about living in a relative’s home, they returned to Hiroshima.

After becoming a teacher at Honkawa Elementary School (in today’s Naka Ward), her day was filled with children. But in the evening, too, she and other members of her family continued working at part-time jobs. Her only solace was singing songs with her three siblings when they lay in their futons at night.

When she was 22, Ms. Yamagiwa came down with tuberculosis (TB), a deadly disease at that time. With thoughts of her siblings in her head, she was determined not to die. Her recovery took three years, but the fact that she was able to still receive part of her salary was a great relief. During the time she was hospitalized, survival itself became her work. Each morning she awoke in her sick bed, still alive, was a cause to give thanks.

Ms. Yamagiwa did not marry. It was an era when balancing work and family was difficult. Taking her mother and her brother, who went on to college, into account, she refrained from getting married, although the chance had come her way. Although she did not begin a new family, her siblings, who she watched grow and go off to live adult lives, were like her own children.

After the atomic bombing, which she bitterly resents, she lived an anxious life each day, faced with poverty and illness. On August 6, 1999, about 10 years after she retired as the principal of Yoshijima Elementary School in Naka Ward, she heard these unforgettable words in the mayor’s annual Peace Declaration:

“They hovered between life and death in a corpse-strewn sea of rubble and ruin--circumstances under which none would have blamed them had they chosen death. Yet they chose life. We should never forget the will and courage that made it possible for the hibakusha to continue to be human.” Hearing these words, Ms. Yamagiwa wept without end. She said, “The many hardships I faced made me think that I’d rather die. But I held out. I felt like my efforts were acknowledged when I heard those words.”

It is unclear whether her experience of the bombing, when she entered the city in the aftermath of the blast, is connected to her recent illness, but in the fall she underwent surgery for cancer. Ms. Yamagiwa feels that sharing her experiences with children is the final work of her life. She sees the children who listen to her as her siblings, back when they were young. She tells them, “When the atomic bomb was dropped, my younger sisters and brother were about your age. Please think about the atomic bombing as something that happened to you, too. No matter what, we must not wage war again.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Read more about the atomic bombing

Her description of “large columns of flame” left a strong impression on me. The horrifying and devastating power of the atomic bomb could be seen even at a place 12 kilometers from the hypocenter. I would like to know more by reading the accounts written by A-bomb survivors and other information so I can convey the reality of the atomic bombing to many others and help prevent this from happening again. (Oai Nakagawa, second-year student in junior high school)

Listen like it happened to us

Ms. Yamagiwa said, “The most horrifying thing about war is when our sense of humanity is destroyed.” We must listen to the A-bomb experiences as something that happened to us, instead of just listening without awareness. I would like to help hand down their experiences and messages so a tragedy like this, where so many people were killed and injured, will never happen again. (Nako Yoshimoto, third-year student in junior high school)

Mission to convey what we have heard

Ms. Yamagiwa seems happy when children listen to her experience seriously and write essays for her about their impressions. On the other hand, she pointed out that her efforts are meaningless if the people who listen to her account don’t pass on what they heard and felt. I am very aware that learning itself is not enough. We must also make creating an environment to convey what we have heard part of our mission. For example, I think that school is the best place to engage in discussion about this. (Kohei Hayashi, first-year student in high school)

(Originally published on December 1, 2014)