Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 3

Feb. 10, 2015

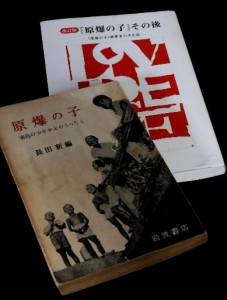

Children of the Atomic Bomb: Testament of the Boys and Girls of Hiroshima, published in 1951

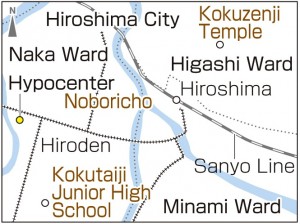

The temple she mentioned in her account of the atomic bombing was this one: Kokuzenji Temple, located at the foot of Mt. Futaba, north of Hiroshima’s main train station, its main hall and priests’ quarters now designated important cultural assets. Yukiko Nitta (nee Yoshida), 78, a resident of Asaminami Ward, gazed about the temple grounds with grave emotion. “I found my mother by the temple gate,” she said.

“If only there had been no war”

On August 9, 1945, Ms. Nitta, then 9 years old, entered the charred plain of the city three days after the bombing. She came from the village of Wada (now part of Miyoshi in northern Hiroshima Prefecture), where she had been evacuated earlier to a relative’s house, to search for her mother Teruyo, who was 31 at the time. She learned from her younger sisters Umeyo, then eight, and Toyoko, then five, where their mother could be found. The younger sisters had experienced the atomic bombing while at their home in Nobori-cho (now part of Naka Ward).

Six years later, Ms. Nitta wrote down the account of her A-bomb experience in her third year at Kokutaiji Junior High School (in Naka Ward), considering it only “a homework assignment for school.”

“Mother was sitting on a broken straw mat,” she wrote, “waiting for us to come.”

Though Ms. Nitta and a relative managed to take her mother home from Kokuzenji Temple, “Mother finally departed for another world on September 9.” Her two younger sisters also passed away, one after the other. Ms. Nitta concluded her A-bomb account with the words: “If only there had been no war, our whole family would have enjoyed happy lives.”

Ms. Nitta said, “I wrote what happened. If I had known it would be included in a book, I would have softened it a bit.” Her account was one of those chosen for Children of the Atomic Bomb, which was published in October 1951 by Iwanami Shoten and is still read widely today.

The book was compiled by Arata Osada (1887-1961), then a professor in the Faculty of Education at Hiroshima University. Seriously wounded in the atomic bombing, Mr. Osada was a leader in rebuilding Hiroshima University after the war and in the peace movement.

In the preface to the book, Mr. Osada wrote that, through the A-bomb experiences of these boys and girls, the reader could “reflect on what effects the atomic bombing imposed on the human spirit.” Their accounts can be used for peace education, too, he said. In all, Mr. Osada and his students gathered 1,175 A-bomb accounts and chose 105 essays from 33 elementary schools, junior high schools, high schools, and colleges in and around Hiroshima. He also quoted from 84 other essays in the book’s long preface.

Children of the Atomic Bomb was met with a strong response. The book inspired two movies, one in 1952, a year after it was published, and the other in 1953. To date, some 270,000 copies have been sold, including a smaller version. Translated into 14 languages, the book has been a remarkable long-seller among publications on the atomic bombing.

Some chose to stay silent

Although the sorrows and appeals for peace by the boys and girls in the book attracted much sympathy, more than a few contributors chose to stay silent after that.

“It’s because our lives continued to be hard after our accounts were brought together for the book,” said Yuriko Hayashi (nee Yamamura), 78, a resident of Asaminami Ward. Ms. Hayashi is the head of the Oleander Club, a friendship group comprised of contributors to the book.

In 1999, Ms. Hayashi compiled a new book titled Children of the Atomic Bomb: Since Then which featured 33 accounts and other information. She took a positive tone in writing about her own life, including her marriage, the difficulties she experienced in having children, her mother’s death from A-bomb-related illness, and her own struggle to overcome breast cancer. At the same time, short, anonymous comments from 11 people indicated that peace of mind was hard for them to find after the atomic bombing.

Ms. Nitta also contributed an account for the new book. She wrote, “Because I felt lonely after losing my mother, I did my best to raise my children so they wouldn’t feel the same way.”

After graduating from junior high, she began working at such places as a bakery and a print shop. At the age of 20, she fell in love and got married, then gave birth to two daughters. After running an okonomiyaki restaurant [a local specialty, a kind of crepe with pork and cabbage], she and her husband Yoshio launched a building management company. Today Ms. Nitta has five grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren, the oldest of whom is four year old. This past New Year’s Day, too, family members sat before the Nitta family altar, which enshrines her late mother and husband.

Her elder daughter Hatsumi Kato, 58, a resident of Saeki Ward, worked as a nurse at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-Bomb Survivors Hospital for 34 years. Ms. Kato said, “When I think back to that time, I was always working with my mother’s thoughts in mind.”

Ms. Nitta asked her grandchildren to read Children of the Atomic Bomb when they reached their teens, as she believes “A-bomb accounts written with pure feelings may be the easiest to understand.” She hopes they will also read Children of the Atomic Bomb: Since Then in the future.

The Oleander Club published a revised edition of the book two years ago. They plan to produce another updated edition this year in the hope of relating how the contributors to the original book have lived their lives and conveying to future generations the importance of living in peace.

(Originally published on February 2, 2015)