Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Impact of the nuclear accident in Fukushima

Feb. 17, 2015

by Masakazu Domen and Jumpei Fujimura, Staff Writers

Nearly four years have passed since the Great East Japan Earthquake, which resulted in the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The accident has been designated a level 7 disaster on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES), the same level as the accident at Chernobyl nuclear power plant. The accident in Japan has caused extensive damage and has made us once again question: Can human beings truly coexist with nuclear weapons or nuclear power? As a consequence, the situation in Hiroshina, with the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing looming on the horizon, is undergoing change. The Chugoku Shimbun considers the reflections of A-bomb survivors on their past attitudes and actions and the efforts of A-bomb survivors’ organizations in newly calling for an end to the use of nuclear energy.

The closest nuclear power plant to Hiroshima is Shikoku Electric’s Ikata plant in Ehime Prefecture. It lies some 100 kilometers southwest of Hiroshima. Since December 2011, many lawsuits have been filed which seek the suspension of operations at the plant. Many of the plaintiffs are members of Ehime Prefecture’s A-bomb survivors’ association.

“The accident at the nuclear plant in Fukushima called for serious reflection,” said Hideto Matsuura, 69, the executive director of the group. Until that time, he had been unaware that Japan had as many as 54 nuclear reactors. In court, he shared his uneasiness about his status as a survivor who suffered prenatal exposure to radiation from the atomic bomb. He called for the elimination of nuclear power, contending that nuclear weapons and nuclear energy are twins.

30 groups hold joint rally

Last November, a rally was held in Saitama to call for the elimination of nuclear power plants in Japan. Leading the protest march in the city center was Terumi Tanaka, 82, secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). Mr. Tanaka, a resident of Niiza, Saitama Prefecture, led the anti-nuclear energy event, one of the largest in the prefecture, as the head of the executive committee comprised of representatives of 30 groups, including Nihon Hidankyo.

The annual event was launched three years ago. Those running the event asked Mr. Tanaka to head the committee, saying that different groups would be more firmly united under the leadership of an A-bomb survivor. He felt this was another useful role he could play, precisely because he was a survivor.

When Nihon Hidankyo was established in 1956, its mission statement clearly supported “the peaceful use of nuclear energy.” In retrospect, said Mr. Tanaka, “We were hoping that such enormous power could be taken full advantage of, not for killing but for the happiness of human beings.”

Following the accidents at Three Mile Island in the United States and Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union, Nihon Hidankyo called for an energy policy designed to promote sources of energy other than nuclear power. But the organization did not call for reactors to be decommissioned because most members believed that their movement should be focused on the abolition of nuclear arms rather than the contentious and divisive issue of nuclear energy. Another consideration involved survivors who were working in the electric power industry.

Fukushima accident major turning point

Mr. Tanaka said, “Damage caused by radiation can’t be seen, and keeps you in a permanent state of anxiety. Most A-bomb survivors realize that we have to get rid of the nation’s nuclear power plants.” Four months after the Fukushima accident, Hidankyo held a meeting of its board of directors in Tokyo and decided to include the following demands into their action policy: To cancel plans to make new or additional nuclear power plants and to stop operations at all existing nuclear reactors and decommission them. Since that time, this “withdrawal from the use of nuclear power” has been one of the pillars of their policy.

Touch of self-reproach

Those demonstrating in front of the prime minister’s official residence, with a call to end the use of nuclear energy in Japan, are not demanding the abolition of nuclear weapons, too. One of the leaders of the movement, Misao Redwolf, said, “I believe that nuclear arms should be eliminated as well. But if we bring up the abolition of nuclear weapons, it will be hard to hold this movement together.” According to Ms. Redwolf, a native of Hiroshima, activists can agree on the immediate problem of nuclear power plants, but hold differing views toward nuclear arms. People tend to see the issue of nuclear weapons, she said, as a problem of national security involving ideologies and deterrence.

Mr. Tanaka sees a parallel between the movement focused on ending nuclear energy and the history of his group. “If they think nuclear power plants are dangerous, nuclear weapons are more dangerous. Many people used to believe that Japan would never suffer an accident like this at a nuclear plant. So they should exercise their imagination and imagine how nuclear weapons could be used at any time,” he said with a touch of self-reproach.

--------------------------

Major incidents involving Japan’s nuclear energy policies and survivors’ movements

August 1945:

Atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

March 1954:

Crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, are exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test.

April 1954:

First budget linked to nuclear energy is passed.

August 1955:

The first World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs is held.

September 1955:

The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo) is established.

November 1955:

Exhibition on the “peaceful use of atomic energy” is held in Tokyo, and in Hiroshima the following May.

December 1955:

The Basic Atomic Energy Act is enacted with three principles: democratic, independent, and public.

January 1956:

The Japan Atomic Energy Commission is established at the Prime Minister’s Office (now, the Cabinet Office).

May 1956:

The Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations is established.

August 1956:

The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) is established.

April 1957:

The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law is enforced.

July 1957:

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is established. Japan joins the IAEA.

November 1961:

The National Council for Peace and Against Nuclear Weapons (Kakkin) is established.

October 1963:

First nuclear power generation in Japan begins in Tokaimura in Ibaraki Prefecture.

July 1964:

Clash of opinions over campaign policies splits the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations into two groups of the same name.

February 1965: The Japan Congress against A- and H- Bombs (Gensuikin) is established.

September 1968:

The A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law goes into effect.

November 1970:

Gensuikin’s national gathering advocates ending the use of nuclear energy for the first time.

March 1971:

The Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant begins commercial operations.

March 1974:

Unit No. 1 of the Chugoku Electric Power Company’s Shimane nuclear power plant begins commercial operations.

June 1976:

Japan joins the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT).

March 1979:

An accident occurs at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in the United States.

June 1982:

The mayor of Kaminoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture announces at the town assembly his intention to invite a nuclear power plant to the town.

April 1986:

An accident occurs at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union.

July 1995:

The Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law goes into effect.

December 1995:

A sodium-leak accident occurs at the fast-breeder reactor Monju in Tsuruga, Fukui Prefecture.

September 1999:

A criticality accident occurs at JCO, a nuclear fuel processing plant, in Tokaimura, Ibaraki Prefecture.

January 2001:

The Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency is established.

October 2003:

The first basic energy policy, which includes promoting nuclear power generation, is approved.

March 2011:

An accident occurs at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, triggered by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

June 2011:

Nihon Hidankyo adopts a policy which calls on the national government to abolish the use of nuclear energy.

September 2012:

The Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency is abolished. The Nuclear Regulation Authority and its Secretariat are established.

February 2014:

The fourth basic energy policy is adopted. The policy deems nuclear energy “an important base-load energy” and stipulates that idle reactors will be restarted.

--------------------------

With the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing drawing near, the Chugoku Shimbun carried out a nationwide survey to learn the views of survivors. To the question “What actions would you like to take, or what is important to you as a survivor?”, 52.6 percent of the respondents chose, among other options, “Create a society that does not depend on the power of the atom, including the use of nuclear energy.” This was the second largest figure among the nine choices, after “Call on the Japanese government and the governments of other nations to make further diplomatic efforts to eliminate nuclear weapons,” which was chosen by 60.5 percent of the respondents. (Multiple answers were allowed.)

In the section where respondents could write freely, some offered their perceptions, from the perspective of an A-bomb survivor, on the accident in Fukushima or their honest opinions about the government’s policy involving nuclear energy.

Survivors’ awareness heightened

◆ After I was exposed to radiation from the bomb, my white cell count decreased, and I’ve been prone to illness. My life has been tough. If it had not been for the nuclear accident in Fukushima, I would have wished to just erase these painful memories. But now I want to speak out loudly and say that nuclear weapons are dreadful. I will communicate this to my children and grandchildren. (Female in her 70s, Tokyo)

◆ Once an explosion or an accident occurs, nuclear weapons or nuclear power plants will cause irreparable and inhumane damage. I become more and more concerned about the effect of radiation as I grow older. I don’t want others to have to feel this same anxiety. I’d like to say to younger people, “Do not create more hibakushas.” I will be more actively involved in sharing my experience. (Male in his 70s, Chiba)

◆ I want to convey the horror of the atomic bombing, the fear of contracting A-bomb diseases, and the suffering that those diseases bring. Many people have experienced great suffering because of the nuclear accident in Fukushima. I will argue for the need to shift to natural sources of energy. (Male in his 70s, Tokyo)

Time to question peaceful use

◆ New hibakushas are being created by nuclear power plants. I feel ashamed of myself, as a hibaksuha, for easily accepting nuclear power plants and the peaceful use of nuclear energy. (Female in her 70s, Hyogo)

◆ Are the existing nuclear power plants really for the peaceful use of nuclear energy? Do they help advance the elimination of nuclear weapons? I want young people to give serious thought to these questions. (Male in his 70s, Osaka)

◆ Japan has a large amount of plutonium extracted from spent nuclear fuel from power plants. The amount is believed to be enough to make 5,000 nuclear weapons, and Japan is thought to be capable of making atomic bombs. We must do away with all our nuclear power plants. (Male in his 80s, Hiroshima)

◆ Some people argue that nuclear power plants should be maintained (for nuclear deterrence) because plutonium from spent fuel can be used for building nuclear weapons. I am adamantly opposed to this view. (Male in his 80s, Tottori)

Honest opinions about nation’s nuclear energy policy

◆ Japan, as a nation that experienced atomic bombings, should be leading the anti-nuclear weapon and anti-nuclear energy movements. It is unforgivable that Japan is trying to sell nuclear power plants to other countries. (Male in his 80s, Hokkaido)

◆ I can’t understand why the Japanese government is trying to export nuclear power plants when it isn’t able to get the crippled nuclear power plant under control. (Female younger than 70, Tokyo)

◆ Once an accident happens, the power of the atom can’t be controlled by human beings. This is obvious from the accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima. Since none of them are absolutely safe, nuclear power plants should not be restarted. (Female in her 70s, Saga)

◆ We should not let operations be resumed at nuclear power plants, and exporting them is absolutely outrageous. What if there is an accident at a power plant Japan exported? Or what if they make nuclear warheads using plutonium? This is not something someone can take responsibility for. (Male in his 70s, Tokyo)

◆ Human beings have discovered the powerful and mighty nuclear power, so they will definitely use it in the future. Efforts should be made to use this power peacefully, facing up to its benefits and risks. (Male in his 80s, Hyogo)

Diverse hopes for the future

◆ Young people, who were born in peaceful times, have led a comfortable life made possible by electricity from nuclear power plants. They may not have a sense of reality about nuclear weapons. But the seriousness of the problem of nuclear power has been made clear by the Fukushima accident. I will communicate the problem through recent incidents in a way that’s easy for others to understand. (Female younger than 70, Hiroshima)

◆ The Japanese people have very short memories. People seem to have forgotten that the war, the atomic bombings, and the nuclear accident really happened. Ignoring the dangers of radiation, they’re trying to restart the nuclear power plants. I would rather be poor and live a safe and peaceful life than be rich and lead a convenient life that’s dangerous. (Male in his 70s, Nagano)

◆ Considering the absolute shortage of resources, we can’t afford to stick to an idealized idea of no nuclear power plants. To younger generations, the horror of the atomic bombings may not seem real, but the nuclear accident in Fukushima must still be fresh in their minds. I hope they will hold discussions and have flexible ideas. (Male in his 70s, Tokyo)

◆ I sometimes think that the human race may become bathed in radiation and go extinct. But I want to believe that the more difficult the situation is, the wiser people can be and they can overcome these challenges. Before my life comes to an end, I want to help the situation move even one step in a positive direction. (Male in his 80s, Tokyo)

◆ Nuclear weapons still exist and nuclear power plants exist close to us. I hope younger people will view the current situation as a problem that affects them, too, and do whatever they can. (Female in her 80s, Hiroshima)

--------------------------

Atsushi Hoshino, resident of Fukushima Prefecture

The decontamination of Atsushi Hoshino’s house began nearly three years after the nuclear accident. First the roof was washed, then more than six months later, the soil on the surface of his garden was removed. Even today, decontamination work continues in the affected areas. “Honestly speaking, why has all this taken such a long time?” said Mr. Hoshino, 86, who lives in the city of Fukushima, about 65 kilometers from the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Mr. Hoshino is also an A-bomb survivor.

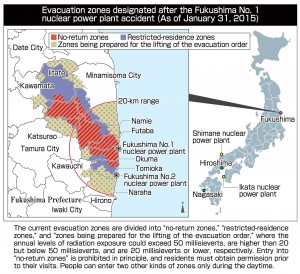

But the time-consuming task testifies to the scale and seriousness of the contamination. At the nuclear plant, efforts to deal with radiation-contaminated water has run into difficulties, which is delaying the process of decommissioning the reactors. As of January, the evacuation zones cover about 1,000 square kilometers of the surrounding 10 municipalities.

“The accident has created irreversible consequences,” Mr. Hoshino said. “My heart aches when I think of the people who were forced to leave the places that are familiar to them.” As the secretary general of the Fukushima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organization, he devoted himself to confirming the whereabouts of some 70 members of the organization in the immediate aftermath of the disaster and the accident. “Some members moved to other prefectures. Others are unable to return from their temporary residences. I have no idea how many people have not returned to their homes if I include people who aren’t survivors.”

After graduating from the faculty of agriculture at the University of Tokyo, Mr. Hoshino, an expert in agricultural economy, taught at Fukushima University. He later became president of the university. He conducted research on the farming and fishing communities of the prefecture and knows that people have a deep attachment to the land of their ancestors. This is why he feels strongly that the accident was an unpardonable wrong.

“Many people around here worked at facilities connected to the nuclear power plant,” Mr. Hoshino said. “So we couldn’t argue loudly against nuclear energy in our campaign to support A-bomb survivors. But things have changed. We must raise our voices.”

On the morning of August 6, 70 years ago, he was on a train going from Hiroshima to Kure, his hometown, when he saw a blue flash from the window. Getting off the train at Hiro Station near Kure, he looked back to see a mushroom-shaped cloud rising into the sky. He was 17 at the time, a first-year student at the former Hiroshima High School.

The next morning, he began helping with relief efforts for the wounded in Hiroshima. The scenes are seared into his memory. He brought one of his classmates to the school dormitory, but his friend’s face was charred, and all he could do was moisten the boy’s lips with water. “What I saw at that time is different from what’s happening now in Fukushima,” Mr. Hoshino said. “But the root of both problems is atomic energy. Human beings can’t control atomic bombs or nuclear power plants.”

◇

Hirotoshi Sano, resident of Tokyo

Hirotoshi Sano, 86, a resident of Mitaka, Tokyo, is a specialist of radiochemistry, the chemical study of radioactive substances. He has written textbooks for university students and supported research which provides a foundation for the nuclear industry.

After the accident at the nuclear plant in Fukushima, one question has echoed in his mind: “Are nuclear power plants ethically acceptable?” Mr. Sano and Mr. Hoshino are the same age and both are survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bombing. “Now I share the same feeling as Mr. Hoshino,” said Mr. Sano.

Mr. Sano taught at Tokyo Metropolitan University for many years and served as its president. He began teaching at the university at the invitation of the late Jinzaburo Takagi. Both men had graduated from the faculty of science at the University of Tokyo. Mr. Takagi was later known as an anti-nuclear energy researcher with no formal institutional affiliation. “I distanced myself from Mr. Takagi,” said Mr. Sano, who had confidence in Japan’s technological prowess and believed that “Nuclear substances are safe and useful as long as they are confined.”

After the nuclear accident, his doubts grew. “Not about our technological ability. But even if we have the technology, human beings will make mistakes. If we make a mistake at a nuclear power plant, can the problems be rectified?” He has been communicating his thoughts at gatherings of the local A-bomb survivors’ group and through its newsletters. “I believed in the ‘safety myth’ of nuclear power,” he said.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Mr. Sano was mobilized to work in the town of Otake, which is located at the western edge of Hiroshima Prefecture. On the morning after the bombing, he went back to the city of Hiroshima to search for his mother. He walked around the scorched city for five days until he finally found her at an aid station in Saka Town. After graduating from the Hiroshima Technical Institute, he went to the University of Tokyo to study radiochemistry. “Part of the reason was that I wanted to know what the atomic bomb really was,” said Mr. Sano. When he told his mother about his major, she lamented his choice, saying, “Out of everything you could have studied, why did you choose that?”

In 1954, when he was a graduate student at the university, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a tuna fishing boat, was exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test. He collected samples of rain containing radioactive substances on the rooftop of his laboratory building. Mr. Sano said, “Looking back, I shouldn’t have done that, but those samples were valuable research materials.” At that time, even ordinary people used the names of radioactive elements, such as cesium-137 or strontium-90, in their daily conversations. They were afraid of being exposed to radiation. “It seems those days are back again, and this time it will last much longer,” he said with a grim expression.

“Human beings are unable to completely control nuclear substances. It takes tens of thousands of years to detoxify nuclear contamination, and it is ethically unacceptable. We must eliminate the possibility of nuclear contamination.” This is what the researcher from Hiroshima has concluded from his academic studies.

--------------------------

How can we overcome repeated mistakes?

Japan, which experienced the atomic bombings, also suffered a major nuclear accident in eastern Japan. What are the implications in connection with the nuclear abolition movement and public opinion? The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Osamu Fujiwara, a professor at Tokyo Keizai University and an authority on the history of Japan’s pacifist movement, including the ban-the-bomb movement.

Almost four years have passed since the nuclear accident. What impact do you think the accident has had on public opinion in Japan? The accident has led people to think that it’s quite contradictory for Japan, which has been calling for the world’s nuclear weapons to be abolished, to also be one of the major users of nuclear energy. People also started to reflect on the fact that the problem of radiation exposure suffered by workers at nuclear power plants has not been given sufficient consideration compared to the damage done by the atomic bombings or the plight of the A-bomb survivors.

The appeal for the abolition of nuclear arms is based on national consensus because the Japanese people support the cause of peace in the world. This is different from the idea or foundation of calling for an end to the use of nuclear energy. We need to be conscious of this and figure out how to connect these two issues.

Do you think the accident has once again forced us to identify the basic problem: Can human beings coexist with the power of the atom? We must remember that the early ban-the-bomb movement gained momentum after radiation-contaminated tuna became a serious problem following the incident involving the Daigo Fukuryu Maru. People became keenly aware that a ban on nuclear and hydrogen bombs was related to their daily lives, and many people became engaged in the movement. The problem of Fukushima is also closely entwined with our lives in such areas as the safety of the food supply and sources of energy.

Nuclear weapons are considered so inhumane that they cannot be seen as instruments of war any longer. The scale of the nuclear accident has raised the quandary of atomic power itself: the power of the atom, including its peaceful use, is beyond the control of human civilization. In this sense, the coexistence of human beings and the power of the atom is being questioned.

How do you interpret the significance of the nuclear accident occurring in Japan, which experienced the atomic bombings? After the war, Japan made a clean break from militarism and unscientific myth. It should have developed as a nation of peace, democracy, and technology. But it has suffered a nuclear accident among the worst in the world. This country repeated another indefensible mistake, just like the war.

The false belief that Japan could never be beaten drove the nation into war, leading to the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The “safety myth” led to dependence on nuclear power, resulting in the accident in Fukushima. Both are based on a weakness in Japanese society, where objections are disregarded and waved aside. The peace movement was focused on non-nuclear policy and steadfastly maintaining the pacifist Constitution. How can we overcome this? The key is to strengthen our democracy.

Profile

Osamu Fujiwara

Osamu Fujiwara graduated from the faculty of law at the University of Tokyo. After serving as an assistant at the university and a special staffer at the International Peace Research Institute at Meiji Gakuin University, he assumed his current post in 2007. He co-authored Ima heiwa towa nanika (What is Peace Now?).

(Originally published on January 31, 2015)

Nearly four years have passed since the Great East Japan Earthquake, which resulted in the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The accident has been designated a level 7 disaster on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES), the same level as the accident at Chernobyl nuclear power plant. The accident in Japan has caused extensive damage and has made us once again question: Can human beings truly coexist with nuclear weapons or nuclear power? As a consequence, the situation in Hiroshina, with the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing looming on the horizon, is undergoing change. The Chugoku Shimbun considers the reflections of A-bomb survivors on their past attitudes and actions and the efforts of A-bomb survivors’ organizations in newly calling for an end to the use of nuclear energy.

A-bomb survivors’ organizations now seek to eliminate both nuclear weapons and nuclear energy

The closest nuclear power plant to Hiroshima is Shikoku Electric’s Ikata plant in Ehime Prefecture. It lies some 100 kilometers southwest of Hiroshima. Since December 2011, many lawsuits have been filed which seek the suspension of operations at the plant. Many of the plaintiffs are members of Ehime Prefecture’s A-bomb survivors’ association.

“The accident at the nuclear plant in Fukushima called for serious reflection,” said Hideto Matsuura, 69, the executive director of the group. Until that time, he had been unaware that Japan had as many as 54 nuclear reactors. In court, he shared his uneasiness about his status as a survivor who suffered prenatal exposure to radiation from the atomic bomb. He called for the elimination of nuclear power, contending that nuclear weapons and nuclear energy are twins.

30 groups hold joint rally

Last November, a rally was held in Saitama to call for the elimination of nuclear power plants in Japan. Leading the protest march in the city center was Terumi Tanaka, 82, secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). Mr. Tanaka, a resident of Niiza, Saitama Prefecture, led the anti-nuclear energy event, one of the largest in the prefecture, as the head of the executive committee comprised of representatives of 30 groups, including Nihon Hidankyo.

The annual event was launched three years ago. Those running the event asked Mr. Tanaka to head the committee, saying that different groups would be more firmly united under the leadership of an A-bomb survivor. He felt this was another useful role he could play, precisely because he was a survivor.

When Nihon Hidankyo was established in 1956, its mission statement clearly supported “the peaceful use of nuclear energy.” In retrospect, said Mr. Tanaka, “We were hoping that such enormous power could be taken full advantage of, not for killing but for the happiness of human beings.”

Following the accidents at Three Mile Island in the United States and Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union, Nihon Hidankyo called for an energy policy designed to promote sources of energy other than nuclear power. But the organization did not call for reactors to be decommissioned because most members believed that their movement should be focused on the abolition of nuclear arms rather than the contentious and divisive issue of nuclear energy. Another consideration involved survivors who were working in the electric power industry.

Fukushima accident major turning point

Mr. Tanaka said, “Damage caused by radiation can’t be seen, and keeps you in a permanent state of anxiety. Most A-bomb survivors realize that we have to get rid of the nation’s nuclear power plants.” Four months after the Fukushima accident, Hidankyo held a meeting of its board of directors in Tokyo and decided to include the following demands into their action policy: To cancel plans to make new or additional nuclear power plants and to stop operations at all existing nuclear reactors and decommission them. Since that time, this “withdrawal from the use of nuclear power” has been one of the pillars of their policy.

Touch of self-reproach

Those demonstrating in front of the prime minister’s official residence, with a call to end the use of nuclear energy in Japan, are not demanding the abolition of nuclear weapons, too. One of the leaders of the movement, Misao Redwolf, said, “I believe that nuclear arms should be eliminated as well. But if we bring up the abolition of nuclear weapons, it will be hard to hold this movement together.” According to Ms. Redwolf, a native of Hiroshima, activists can agree on the immediate problem of nuclear power plants, but hold differing views toward nuclear arms. People tend to see the issue of nuclear weapons, she said, as a problem of national security involving ideologies and deterrence.

Mr. Tanaka sees a parallel between the movement focused on ending nuclear energy and the history of his group. “If they think nuclear power plants are dangerous, nuclear weapons are more dangerous. Many people used to believe that Japan would never suffer an accident like this at a nuclear plant. So they should exercise their imagination and imagine how nuclear weapons could be used at any time,” he said with a touch of self-reproach.

--------------------------

Major incidents involving Japan’s nuclear energy policies and survivors’ movements

August 1945:

Atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

March 1954:

Crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, are exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test.

April 1954:

First budget linked to nuclear energy is passed.

August 1955:

The first World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs is held.

September 1955:

The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo) is established.

November 1955:

Exhibition on the “peaceful use of atomic energy” is held in Tokyo, and in Hiroshima the following May.

December 1955:

The Basic Atomic Energy Act is enacted with three principles: democratic, independent, and public.

January 1956:

The Japan Atomic Energy Commission is established at the Prime Minister’s Office (now, the Cabinet Office).

May 1956:

The Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations is established.

August 1956:

The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) is established.

April 1957:

The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law is enforced.

July 1957:

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is established. Japan joins the IAEA.

November 1961:

The National Council for Peace and Against Nuclear Weapons (Kakkin) is established.

October 1963:

First nuclear power generation in Japan begins in Tokaimura in Ibaraki Prefecture.

July 1964:

Clash of opinions over campaign policies splits the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations into two groups of the same name.

February 1965: The Japan Congress against A- and H- Bombs (Gensuikin) is established.

September 1968:

The A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law goes into effect.

November 1970:

Gensuikin’s national gathering advocates ending the use of nuclear energy for the first time.

March 1971:

The Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant begins commercial operations.

March 1974:

Unit No. 1 of the Chugoku Electric Power Company’s Shimane nuclear power plant begins commercial operations.

June 1976:

Japan joins the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT).

March 1979:

An accident occurs at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in the United States.

June 1982:

The mayor of Kaminoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture announces at the town assembly his intention to invite a nuclear power plant to the town.

April 1986:

An accident occurs at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union.

July 1995:

The Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law goes into effect.

December 1995:

A sodium-leak accident occurs at the fast-breeder reactor Monju in Tsuruga, Fukui Prefecture.

September 1999:

A criticality accident occurs at JCO, a nuclear fuel processing plant, in Tokaimura, Ibaraki Prefecture.

January 2001:

The Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency is established.

October 2003:

The first basic energy policy, which includes promoting nuclear power generation, is approved.

March 2011:

An accident occurs at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, triggered by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

June 2011:

Nihon Hidankyo adopts a policy which calls on the national government to abolish the use of nuclear energy.

September 2012:

The Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency is abolished. The Nuclear Regulation Authority and its Secretariat are established.

February 2014:

The fourth basic energy policy is adopted. The policy deems nuclear energy “an important base-load energy” and stipulates that idle reactors will be restarted.

--------------------------

Survey responses from A-bomb survivors: 52.6% hope to end nation’s reliance on nuclear energy

With the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing drawing near, the Chugoku Shimbun carried out a nationwide survey to learn the views of survivors. To the question “What actions would you like to take, or what is important to you as a survivor?”, 52.6 percent of the respondents chose, among other options, “Create a society that does not depend on the power of the atom, including the use of nuclear energy.” This was the second largest figure among the nine choices, after “Call on the Japanese government and the governments of other nations to make further diplomatic efforts to eliminate nuclear weapons,” which was chosen by 60.5 percent of the respondents. (Multiple answers were allowed.)

In the section where respondents could write freely, some offered their perceptions, from the perspective of an A-bomb survivor, on the accident in Fukushima or their honest opinions about the government’s policy involving nuclear energy.

Survivors’ awareness heightened

◆ After I was exposed to radiation from the bomb, my white cell count decreased, and I’ve been prone to illness. My life has been tough. If it had not been for the nuclear accident in Fukushima, I would have wished to just erase these painful memories. But now I want to speak out loudly and say that nuclear weapons are dreadful. I will communicate this to my children and grandchildren. (Female in her 70s, Tokyo)

◆ Once an explosion or an accident occurs, nuclear weapons or nuclear power plants will cause irreparable and inhumane damage. I become more and more concerned about the effect of radiation as I grow older. I don’t want others to have to feel this same anxiety. I’d like to say to younger people, “Do not create more hibakushas.” I will be more actively involved in sharing my experience. (Male in his 70s, Chiba)

◆ I want to convey the horror of the atomic bombing, the fear of contracting A-bomb diseases, and the suffering that those diseases bring. Many people have experienced great suffering because of the nuclear accident in Fukushima. I will argue for the need to shift to natural sources of energy. (Male in his 70s, Tokyo)

Time to question peaceful use

◆ New hibakushas are being created by nuclear power plants. I feel ashamed of myself, as a hibaksuha, for easily accepting nuclear power plants and the peaceful use of nuclear energy. (Female in her 70s, Hyogo)

◆ Are the existing nuclear power plants really for the peaceful use of nuclear energy? Do they help advance the elimination of nuclear weapons? I want young people to give serious thought to these questions. (Male in his 70s, Osaka)

◆ Japan has a large amount of plutonium extracted from spent nuclear fuel from power plants. The amount is believed to be enough to make 5,000 nuclear weapons, and Japan is thought to be capable of making atomic bombs. We must do away with all our nuclear power plants. (Male in his 80s, Hiroshima)

◆ Some people argue that nuclear power plants should be maintained (for nuclear deterrence) because plutonium from spent fuel can be used for building nuclear weapons. I am adamantly opposed to this view. (Male in his 80s, Tottori)

Honest opinions about nation’s nuclear energy policy

◆ Japan, as a nation that experienced atomic bombings, should be leading the anti-nuclear weapon and anti-nuclear energy movements. It is unforgivable that Japan is trying to sell nuclear power plants to other countries. (Male in his 80s, Hokkaido)

◆ I can’t understand why the Japanese government is trying to export nuclear power plants when it isn’t able to get the crippled nuclear power plant under control. (Female younger than 70, Tokyo)

◆ Once an accident happens, the power of the atom can’t be controlled by human beings. This is obvious from the accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima. Since none of them are absolutely safe, nuclear power plants should not be restarted. (Female in her 70s, Saga)

◆ We should not let operations be resumed at nuclear power plants, and exporting them is absolutely outrageous. What if there is an accident at a power plant Japan exported? Or what if they make nuclear warheads using plutonium? This is not something someone can take responsibility for. (Male in his 70s, Tokyo)

◆ Human beings have discovered the powerful and mighty nuclear power, so they will definitely use it in the future. Efforts should be made to use this power peacefully, facing up to its benefits and risks. (Male in his 80s, Hyogo)

Diverse hopes for the future

◆ Young people, who were born in peaceful times, have led a comfortable life made possible by electricity from nuclear power plants. They may not have a sense of reality about nuclear weapons. But the seriousness of the problem of nuclear power has been made clear by the Fukushima accident. I will communicate the problem through recent incidents in a way that’s easy for others to understand. (Female younger than 70, Hiroshima)

◆ The Japanese people have very short memories. People seem to have forgotten that the war, the atomic bombings, and the nuclear accident really happened. Ignoring the dangers of radiation, they’re trying to restart the nuclear power plants. I would rather be poor and live a safe and peaceful life than be rich and lead a convenient life that’s dangerous. (Male in his 70s, Nagano)

◆ Considering the absolute shortage of resources, we can’t afford to stick to an idealized idea of no nuclear power plants. To younger generations, the horror of the atomic bombings may not seem real, but the nuclear accident in Fukushima must still be fresh in their minds. I hope they will hold discussions and have flexible ideas. (Male in his 70s, Tokyo)

◆ I sometimes think that the human race may become bathed in radiation and go extinct. But I want to believe that the more difficult the situation is, the wiser people can be and they can overcome these challenges. Before my life comes to an end, I want to help the situation move even one step in a positive direction. (Male in his 80s, Tokyo)

◆ Nuclear weapons still exist and nuclear power plants exist close to us. I hope younger people will view the current situation as a problem that affects them, too, and do whatever they can. (Female in her 80s, Hiroshima)

--------------------------

A-bomb survivor looks back on path from Hiroshima to Fukushima

Atsushi Hoshino, resident of Fukushima Prefecture

The decontamination of Atsushi Hoshino’s house began nearly three years after the nuclear accident. First the roof was washed, then more than six months later, the soil on the surface of his garden was removed. Even today, decontamination work continues in the affected areas. “Honestly speaking, why has all this taken such a long time?” said Mr. Hoshino, 86, who lives in the city of Fukushima, about 65 kilometers from the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Mr. Hoshino is also an A-bomb survivor.

But the time-consuming task testifies to the scale and seriousness of the contamination. At the nuclear plant, efforts to deal with radiation-contaminated water has run into difficulties, which is delaying the process of decommissioning the reactors. As of January, the evacuation zones cover about 1,000 square kilometers of the surrounding 10 municipalities.

“The accident has created irreversible consequences,” Mr. Hoshino said. “My heart aches when I think of the people who were forced to leave the places that are familiar to them.” As the secretary general of the Fukushima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organization, he devoted himself to confirming the whereabouts of some 70 members of the organization in the immediate aftermath of the disaster and the accident. “Some members moved to other prefectures. Others are unable to return from their temporary residences. I have no idea how many people have not returned to their homes if I include people who aren’t survivors.”

After graduating from the faculty of agriculture at the University of Tokyo, Mr. Hoshino, an expert in agricultural economy, taught at Fukushima University. He later became president of the university. He conducted research on the farming and fishing communities of the prefecture and knows that people have a deep attachment to the land of their ancestors. This is why he feels strongly that the accident was an unpardonable wrong.

“Many people around here worked at facilities connected to the nuclear power plant,” Mr. Hoshino said. “So we couldn’t argue loudly against nuclear energy in our campaign to support A-bomb survivors. But things have changed. We must raise our voices.”

On the morning of August 6, 70 years ago, he was on a train going from Hiroshima to Kure, his hometown, when he saw a blue flash from the window. Getting off the train at Hiro Station near Kure, he looked back to see a mushroom-shaped cloud rising into the sky. He was 17 at the time, a first-year student at the former Hiroshima High School.

The next morning, he began helping with relief efforts for the wounded in Hiroshima. The scenes are seared into his memory. He brought one of his classmates to the school dormitory, but his friend’s face was charred, and all he could do was moisten the boy’s lips with water. “What I saw at that time is different from what’s happening now in Fukushima,” Mr. Hoshino said. “But the root of both problems is atomic energy. Human beings can’t control atomic bombs or nuclear power plants.”

◇

Researcher questions ethical responsibility

Hirotoshi Sano, resident of Tokyo

Hirotoshi Sano, 86, a resident of Mitaka, Tokyo, is a specialist of radiochemistry, the chemical study of radioactive substances. He has written textbooks for university students and supported research which provides a foundation for the nuclear industry.

After the accident at the nuclear plant in Fukushima, one question has echoed in his mind: “Are nuclear power plants ethically acceptable?” Mr. Sano and Mr. Hoshino are the same age and both are survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bombing. “Now I share the same feeling as Mr. Hoshino,” said Mr. Sano.

Mr. Sano taught at Tokyo Metropolitan University for many years and served as its president. He began teaching at the university at the invitation of the late Jinzaburo Takagi. Both men had graduated from the faculty of science at the University of Tokyo. Mr. Takagi was later known as an anti-nuclear energy researcher with no formal institutional affiliation. “I distanced myself from Mr. Takagi,” said Mr. Sano, who had confidence in Japan’s technological prowess and believed that “Nuclear substances are safe and useful as long as they are confined.”

After the nuclear accident, his doubts grew. “Not about our technological ability. But even if we have the technology, human beings will make mistakes. If we make a mistake at a nuclear power plant, can the problems be rectified?” He has been communicating his thoughts at gatherings of the local A-bomb survivors’ group and through its newsletters. “I believed in the ‘safety myth’ of nuclear power,” he said.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Mr. Sano was mobilized to work in the town of Otake, which is located at the western edge of Hiroshima Prefecture. On the morning after the bombing, he went back to the city of Hiroshima to search for his mother. He walked around the scorched city for five days until he finally found her at an aid station in Saka Town. After graduating from the Hiroshima Technical Institute, he went to the University of Tokyo to study radiochemistry. “Part of the reason was that I wanted to know what the atomic bomb really was,” said Mr. Sano. When he told his mother about his major, she lamented his choice, saying, “Out of everything you could have studied, why did you choose that?”

In 1954, when he was a graduate student at the university, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a tuna fishing boat, was exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test. He collected samples of rain containing radioactive substances on the rooftop of his laboratory building. Mr. Sano said, “Looking back, I shouldn’t have done that, but those samples were valuable research materials.” At that time, even ordinary people used the names of radioactive elements, such as cesium-137 or strontium-90, in their daily conversations. They were afraid of being exposed to radiation. “It seems those days are back again, and this time it will last much longer,” he said with a grim expression.

“Human beings are unable to completely control nuclear substances. It takes tens of thousands of years to detoxify nuclear contamination, and it is ethically unacceptable. We must eliminate the possibility of nuclear contamination.” This is what the researcher from Hiroshima has concluded from his academic studies.

--------------------------

Interview with Osamu Fujiwara, professor at Tokyo Keizai University

How can we overcome repeated mistakes?

Japan, which experienced the atomic bombings, also suffered a major nuclear accident in eastern Japan. What are the implications in connection with the nuclear abolition movement and public opinion? The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Osamu Fujiwara, a professor at Tokyo Keizai University and an authority on the history of Japan’s pacifist movement, including the ban-the-bomb movement.

Almost four years have passed since the nuclear accident. What impact do you think the accident has had on public opinion in Japan? The accident has led people to think that it’s quite contradictory for Japan, which has been calling for the world’s nuclear weapons to be abolished, to also be one of the major users of nuclear energy. People also started to reflect on the fact that the problem of radiation exposure suffered by workers at nuclear power plants has not been given sufficient consideration compared to the damage done by the atomic bombings or the plight of the A-bomb survivors.

The appeal for the abolition of nuclear arms is based on national consensus because the Japanese people support the cause of peace in the world. This is different from the idea or foundation of calling for an end to the use of nuclear energy. We need to be conscious of this and figure out how to connect these two issues.

Do you think the accident has once again forced us to identify the basic problem: Can human beings coexist with the power of the atom? We must remember that the early ban-the-bomb movement gained momentum after radiation-contaminated tuna became a serious problem following the incident involving the Daigo Fukuryu Maru. People became keenly aware that a ban on nuclear and hydrogen bombs was related to their daily lives, and many people became engaged in the movement. The problem of Fukushima is also closely entwined with our lives in such areas as the safety of the food supply and sources of energy.

Nuclear weapons are considered so inhumane that they cannot be seen as instruments of war any longer. The scale of the nuclear accident has raised the quandary of atomic power itself: the power of the atom, including its peaceful use, is beyond the control of human civilization. In this sense, the coexistence of human beings and the power of the atom is being questioned.

How do you interpret the significance of the nuclear accident occurring in Japan, which experienced the atomic bombings? After the war, Japan made a clean break from militarism and unscientific myth. It should have developed as a nation of peace, democracy, and technology. But it has suffered a nuclear accident among the worst in the world. This country repeated another indefensible mistake, just like the war.

The false belief that Japan could never be beaten drove the nation into war, leading to the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The “safety myth” led to dependence on nuclear power, resulting in the accident in Fukushima. Both are based on a weakness in Japanese society, where objections are disregarded and waved aside. The peace movement was focused on non-nuclear policy and steadfastly maintaining the pacifist Constitution. How can we overcome this? The key is to strengthen our democracy.

Profile

Osamu Fujiwara

Osamu Fujiwara graduated from the faculty of law at the University of Tokyo. After serving as an assistant at the university and a special staffer at the International Peace Research Institute at Meiji Gakuin University, he assumed his current post in 2007. He co-authored Ima heiwa towa nanika (What is Peace Now?).

(Originally published on January 31, 2015)