Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 7

Mar. 17, 2015

Busy district at hypocenter is obliterated in A-bombing

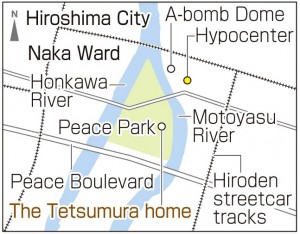

The 12.2 hectares of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, located in Naka Ward, were once known as the Nakajima district, one of the busiest parts of the delta area. The neighborhood which faced the west side of the Motoyasu River was called Tenjin-machi Kitagumi, and it extended about 280 meters north and south. There was a sake wholesaler, a fabric dye shop, a clothing shop, a clinic for internal medicine, among many other businesses. A well-known ryokan (Japanese inn) was located here, too.

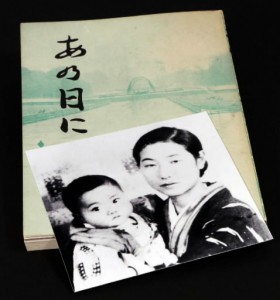

However, the whole district, and the lives of the people who were there at the time, were obliterated when the atomic bomb exploded on August 6, 1945. Thirty years later, a book titled Ano Hi Ni (On That Day) was published. It contained 18 written accounts of Tenjin-machi and memories associated with Nakajima.

“That monument is my grave”

Kyoko Tetsumura (née Shikano), 85, says that the monument for the victims of Tenjin-machi Kitagumi in Peace Memorial Park is her grave. In drizzling rain, and despite advancing age, Ms. Tetsumura visited the monument accompanied by her eldest daughter, Kumiko Seino, 56, a former nurse. They are both residents of Hiroshima.

In Ano Hi Ni, Ms. Tetsumura wrote about what she was forced to face at the age of 15: “I could guess where my house was because there was a round fire prevention water tank that I recognized, but I couldn’t find my mother or brothers there. I thought the dead woman with her head down (on the road) might be my mother, but I couldn’t recognize her because the clothes had been burned. I didn’t have the courage to raise her head and look at her…”

Ms. Tetsumura’s father, who ran an eatery in Nakajima, was killed in the Battle of Guadalcanal. She was living at 27 Tenjin-machi, located within the alley, with her mother and two brothers, but temporarily moved their belongings to a vacant house in the adjacent Zaimoku-cho district in case of air raids.

From that new location, Ms. Tetsumura went to work for the military supply depot in Gion-cho (now Asaminami Ward), which had been evacuated to various sites in anticipation of air raids. On her way there, she saw the bomb’s flash and fled toward a rice field. At the time, she believed it was an incendiary bomb of white phosphorous.

The next day, August 7, she was able to return to her home in Nakajima and she searched for missing family members. But she was unable to find even the remains of her mother, Tsuneko Shikano, who was 41 at the time, or her brothers, Shigeru, then 8 and a student Nakajima Elementary School, and Masaru, then 2.

Turned into a scorched plain, Nakajima was then reborn as Peace Memorial Park after the Peace Memorial City Construction Law, a piece of special national legislation, was enacted in 1949. The Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims was built in 1952 and Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Municipal Auditorium were opened in 1955.

Ms. Tetsumura felt lonely, but she said to herself, “It’s not bad that the place where my family sleeps has become the place where we pray for peace.” After she got married and Kumiko was born, she never failed to attend the Peace Memorial Ceremony on August 6 with her daughter.

Hiroshi Shindo, who ran a clothing shop in Tenjin-machi, compiled Ano Hi Ni. He lent his support to the Hypocenter Reconstruction Study, which Hiroshima University’s former Research Institute for Nuclear Medicine and Biology launched in 1968 to determine the facts of the atomic bombing. In 1973, Mr. Shindo erected the monument for the victims of Tenjin-machi with other former residents of the area.

Ms. Tetsumura’s account also describes the exchange she had with her only daughter, a high school student at the time, about her A-bomb experience. She writes: “I didn’t think she was able to grasp the whole picture of my A-bomb account yet.”

First-generation memory keepers of the A-bomb experience

Forty years later, Kumiko will start to serve as a first-generation “memory keeper” in April. During the three years of her training, organized by the City of Hiroshima, she studied survivors’ accounts and other information related to the Nakajima district. Those who had known her mother seemed to struggle in writing about their suffering, she said. She also felt that the more accounts of the bombing she read, “the more profound it became to hand down these memories.” At the same time, as a memory keeper, she says that she wants to accurately convey the memories of Tenjin-machi that she heard from her mother.

In her childhood, her mother would gobble up ice cream at her father’s shop, swim in the Motoyasu River, and catch freshwater clams and small fish. Kumiko hopes to convey these memories of the family’s peaceful life before the war.

On the monument for the victims of Tenjin-machi Kitagumi are inscribed the names of 272 victims. “Even now, I can see their faces in my mind,” Ms. Tetsumura said, stroking the monument with affection. Lost in thought, she went on sharing memories of the past. “Thank you,” Kumiko told her. “I enjoy hearing your happy memories.”

(Originally published on March 9, 2015)