Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 8

Mar. 25, 2015

A-bomb Survivors in Okinawa, published in 1981

For many years, A-bomb survivors who returned to Okinawa from Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not have access to the relief measures provided to survivors on mainland Japan. Even after the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law went into effect in 1957, the Japanese government said that the law did not apply to survivors living in Okinawa. This was the result of the peace treaty signed between the United States and Japan after the war, which restored Japan’s sovereign rights, but also put Okinawa under the administrative control of U.S. forces.

In 1965, five Okinawa residents, including Tsuru Marumo, who was 58 at the time, filed a lawsuit at the Tokyo District Court, seeking equal treatment under the law. Ms. Marumo first shared her A-bomb experience at a rally in Okinawa to ban atomic and hydrogen bombs, after taking part in a gathering that launched today’s Okinawa Prefecture A-bomb Survivors’ Council (Hibakukyo). This was in 1963, the year before people on the mainland were absorbed by the Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

Sachiko Higa, 82, Ms. Marumo’s daughter, said, “I believe my mother devoted her life to this cause out of the duty she felt as a living witness to the atomic bombing.” Ms. Higa calmly traced her mother’s path when she was interviewed at her home in Naha, Okinawa Prefecture.

Evacuated to Hiroshima a year before the bombing

In the summer of 1944, with Okinawa on the verge of becoming a battleground in the war, Ms. Marumo evacuated to Hiroshima, her husband’s hometown, with her son and daughter. But at the end of that year, her husband died of illness and she began working at a plant which manufactured airplanes to support her family.

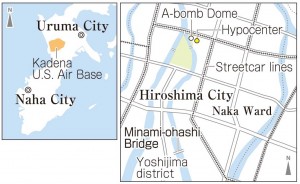

On August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing, Ms. Marumo suffered burns to the left side of her body while at the Minami-ohashi Bridge, which spanned the Motoyasu River, located about 1.75 kilometers from the hypocenter. Ms. Higa, then a first-year student at Jogakuin Girls’ High School, had a fever and was at home in the Yoshijima district (part of present-day Naka Ward). Ms. Marumo managed to return home and Ms. Higa devoted herself to her mother’s care. Her elder brother, Masataka (who passed away at the age of 57 in 1987), worked on a river boat which ferried people around the Hiroshima delta after many bridges were destroyed in the bombing, among other jobs.

In the fall of 1946, Ms. Marumo and her two children returned to Okinawa with their meager belongings. Though Okinawa had also been decimated as the result of the ground war which raged there, they were able to reunite with Ms. Higa’s grandmother and settle in the city of Ishikawa (now Uruma) in the center of Okinawa’s main island.

Because Ms. Marumo suffered from a severe keloid which stretched from her left ear to her neck, she avoided other people. But she summoned enough courage to work for the city office and, by herself, was able to send her two children to universities in Tokyo.

Then Ms. Marumo began to speak out as an A-bomb survivor who had been abandoned by mainland Japan. Her advocacy was also triggered by the crash of a U.S. military jet in 1959, which she witnessed. The plane crashed into Miyamori Elementary School, in her neighborhood, killing 17 people and injuring 210 others. Before it went down, the pilot had jumped to safety.

37 accounts given under pseudonyms

“The blaze after the crash instantly brought me back to my time in Hiroshima. I wonder how long Okinawa will continue to suffer from disaster because of the military bases located here.” This is from the account Ms. Marumo contributed, under the name Hideko Miyagi, to the Okinawa no Hibakusha (A-bomb Survivors in Okinawa). The book consists of 66 accounts based on interviews of A-bomb survivors conducted by Hiroaki Fukuchi, 84, the president of the Okinawa Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Hibakukyo published the book in 1981.

Following the lawsuit filed by Ms. Marumo and others, the Japanese government began applying the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law, with certain modifications, to the residents of Okinawa in 1967. Then, when Japan regained control of Okinawa in 1972, the survivors there could fully access the law’s relief measures. But Mr. Fukuichi said that, nevertheless, 37 accounts in the book were written under pen names: “If people were identified as A-bomb survivors, they weren’t able to get jobs and their appeals for justice were seen as anti-American.”

Ms. Higa, the daughter, worked at such places as a U.S. military base and U.S. military headquarters and kept those experiences hidden away. In 1993, she started to face the atomic bombing squarely when she took part in the Peace Memorial Ceremony, held annually in Hiroshima, as a representative for bereaved families in Okinawa, and visited the high school where she once studied. At the school, she prayed before a memorial inscribed with the names of 141 schoolmates who lost their lives to the atomic bomb as they helped dismantle homes to make fire lanes and in other ways.

Prompted by this experience, Ms. Higa began speaking about her experience of the bombing at schools and community centers. When her mother passed away in 2000 at the age of 93, she took her grandchild, a fifth grader, to the Peace Memorial Ceremony. Since 2003, she has served as the vice chairperson of Hibakukyo. Currently, the organization has 176 members, including 64 who suffered the bombing in Hiroshima. Year by year, this number is decreasing, but as an A-bomb survivor, she has continued carrying on her mother’s legacy by conveying her experiences and thoughts to younger generations.

Sachiko took reporters from Hiroshima to a roadside spot which overlooks the Kadena Air Base. Gazing at the U.S. air station, called the largest in the Far East, she posed one question: “How much concern do the people of mainland Japan show for the reality of Okinawa, which continues to endure extraordinary suffering even today?” During this conversation, the roaring of fighter jets and transport aircraft as they took off and landed persisted without pause.

(Originally published on March 16, 2015)