Teiko Kubo, 78, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

Apr. 2, 2015

Resolved to apply for certificate for grandchildren; feelings of guilt, concern

Desire to be of help

Desire to be of help

by Yumie Kubo, Staff Writer

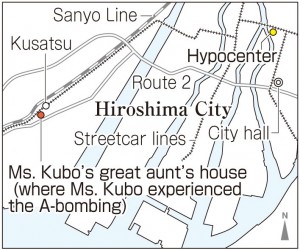

Teiko Kubo (nee Kubota), 78, was 9 years old and in Kusatsu-honmachi (now part of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward), about 4.1 km from the hypocenter, at the time of the atomic bombing. But she did not apply for an atomic bomb survivor’s certificate until 39 years later. She worried about discrimination and tried not to think about the atomic bombing. But when heart disease was discovered in two grandchildren born in 1984, she had feelings of guilt and resolved to get a certificate.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Kubo was a third grader at Fukuromachi National School (now Fukuromachi Elementary School in Naka Ward). Her mother had died when she was 4, and her father had gone to Shimane Prefecture to work. So her grandmother, Misayo (who died in 1968 at the age of 87), looked after her. Ms. Kubo had relocated to Kurahashi Island (now part of Kure) to escape air raids, but she became ill in early August 1945 and moved to the home of her great aunt in Kusatsu-honmachi. She was recuperating there when the atomic bomb was dropped.

The room’s sliding doors suddenly toppled onto her futon as Ms. Kubo slept. Feeling anxious, she stayed in her futon until she was carried to an air raid shelter behind the house by a young man she was unacquainted with. After that she fled to the nearby hills with her grandmother and some neighbors. “The sound of moans was carried on the breeze from the city center,” Ms. Kubo recalled. “It was scary.”

Before relocating to Kurahashi Island, Ms. Kubo had lived with her father and grandmother. Her father ran a café next to the Fukuya department store (in what is now Naka Ward). She recalled playing on the slide on the roof of Fukuya and the lively night stalls. The neighborhood was like a pleasant “dreamland,” she said. But for some time after the atomic bombing she was too frightened to go back there.

After the war Ms. Kubo transferred to Kusatsu National School (now Kusatsu Elementary School in Nishi Ward). Her grandmother, who was like a mother to her, told her that it was important to study because the knowledge she gained could never be taken from her. Ms. Kubo went on to Yasuda Girls’ Junior High and High School (in what is now Naka Ward) and Yasuda Women’s College (in what is now Asa Minami Ward).

Her grandmother supported them by selling shells she got from the sea, but it was a hard life. The corrugated iron roof of their house was so full of holes that they could see the stars at night. Ms. Kubo could not afford to buy a school uniform, so she put a collar on her father’s old uniform, mended it and wore that to school. She could not go to the softball team’s training camp because she could not pay the fee. When she saw her grandmother heading off to the sea on cold days wearing several layers of clothes she wondered if she should quit school and go to work to help out. She attended junior college on a scholarship.

Some of her friends were told by their parents to hide the fact that they were survivors of the atomic bombing or else they would not be able to get married. She thought about her A-bombing experience and decided she had better not let people know about it.

She married at 20 and had four sons. Neither she nor her sons had any serious illnesses.

So she was shocked and very anxious when illness was detected in her grandchildren. She had no idea whether the effects of radiation could be passed down from generation to generation. But she felt that should her grandchildren suffer from illness in the future, proof that their grandmother was an A-bomb survivor might be useful in identifying the cause of their illness and in helping them get partial compensation for their medical costs. With this in mind, she decided to apply for a survivor’s certificate. A cousin who was two years older served as a witness.

Ms. Kubo had never before spoken in detail about her atomic bombing experiences because, when she thought about her friends who had been discriminated against, she was worried about letting people know that she was an A-bomb survivor. But she is happy that her granddaughter (this writer) and other young people have an interest in the atomic bombing and the war. “Parents and children, friends, people of different nationalities and religions – I would like all of them to get along and work toward a world without nuclear weapons,” Ms. Kubo said.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Convey Ms. Kubo’s thought to others

Ms. Kubo said she would like people to work toward a peaceful world by first avoiding spats with their friends and eliminating bullying. I will work even harder as a junior writer, keeping this thought in mind. I would also like those who have read Ms. Kubo’s account of her experiences to avoid arguing and bullying and to urge others to do so as well. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, first-year junior high school student)

Use things with care

Ms. Kubo said that when she was a girl she loved the stems of pumpkins. I couldn’t imagine that they could taste good, I suppose because we live in an age of material abundance today. I’ve never really felt “I want to eat this” or “I wish I had that.” From now on I want to eat my meals with a sense of gratitude and use things with care. (Riho Kito, first-year junior high school student)

Remember gratitude to those around me

Ms. Kubo lost her mother when she was very small and was raised by her grandmother. When I heard about the poverty of her school days and her grandmother’s hardships, I realized what a privileged upbringing I have had. I’m able to live a comfortable life thanks to the people around me. I want to remember to feel grateful, not taking my comfortable life for granted. (Shino Taniguchi, first-year high school student)

(Originally published on March 30, 2015)