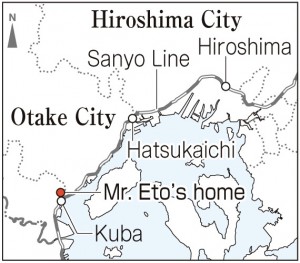

Iwao Eto, 82, Otake City, Hiroshima

Aug. 25, 2014

Sharing the horror of the A-bombing for the first time

by Keita Izumi, Staff Writer

Iwao Eto, 82, had not talked about his experience of the atomic bombing before. Even with his family, he was unable to share the details of his experience. After the war, Mr. Eto worked for a textile plant in the city of Otake and took international visitors who came to the plant to Hiroshima many times to see the sights there. He would lead them to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, but did not enter himself. He sought to avoid the displays that would remind him of the horror he endured that day.

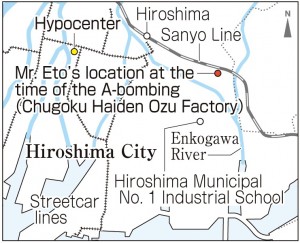

At the time of the bombing, Mr. Eto was a second-year student at the Hiroshima Municipal No. 1 Industrial School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial School in Minami Ward). He was mobilized to work at the Ozu Factory of Chugoku Haiden (now the Chugoku Electric Manufacturing Company in Minami Ward), located about 3.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. That day, he was preparing to work with a lathe.

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, his surroundings were suddenly struck by a flash, like an electrical short. When he looked outside from a window, he saw that everything was colored red and roof tiles had been hurled into the sky. A massive blast then followed in the next moment. When he came to, he found that he had been blown off his feet and was now on the floor. His shaven head had been pierced with many fragments of glass and he suffered a deep gash on his right arm.

Not knowing what had happened, Mr. Eto fled the factory with the other teachers and students, heading to their school. He came across bodies drifting away, one after another, on the surface of the Enkogawa River, their clothes charred. Back at the school, he saw fires rising in the city center. “I only knew that something extraordinary had happened,” he said.

Around 2:30 p.m., he went on foot with five or six other students, who lived in the same direction, toward the town of Kuba (now the city of Otake). Along the way, he saw houses in flames; charred bodies scattered on the road; people crying out over the dead. Witnessing so many horrific scenes, he began to feel numb, even as he stepped over the bodies blocking his path. “My senses were numb,” he explained. “And I felt it was urgent to keep going.”

“I went on walking past the scorching flames by pouring water over myself from wells and crossing rivers neck-deep in the water where there were scores of bodies floating on the surface. Around the time I reached the Kogo district (now in Nishi Ward), trucks had begun transporting the injured. I was told to get on, but I declined. I was so scared of the people on the truck. I’m sorry to say it, but I felt sick when I saw them, with their clothes burned to tatters and their skin peeling off so that their faces were unrecognizable.”

Because trains were still running from Hatsukaichi Station (now in the city of Hatsukaichi), Mr. Eto boarded a train and reached Kuba Station (now in the city of Otake) around 2 a.m. on August 7, the following day. “Many parents came up to me, asking about their children, but I was unable to offer answers,” he said. “I developed diarrhea after the bombing, and I was bedridden for the next month and a half.” A-bomb survivors were taken continuously to a nearby elementary school, but many of them passed away. From his home, Mr. Eto would watch the smoke billow up, day after day, as the bodies were cremated.

He suffered many experiences that he doesn’t want to recall because they were so painful. But he decided to talk about them for this interview, saying, “I’m getting old. I’d like young people to convey the terrible reality of the atomic bombing to others.” He stressed, “War is when people’s actions aren’t considered crimes, no matter how many other people they kill. We mustn’t wage war again. I hope that young people, who will create the future, think about how they can build a world where human beings resolve disputes using words, not force.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Renew determination for our role

Mr. Eto said that he hopes young people like us will convey his experience to others. Listening to him, I again realized that we will be the last generation to hear about the A-bomb experiences directly from the survivors. Committing murder is a crime. But in war, even though people kill so many others, these acts are condoned. Mr. Eto pointed out this absurdity. I’ve taken Mr. Eto’s thoughts to heart and renewed my determination to think seriously about our role in realizing peace. (Marika Tsuboki, 14)

Learn from the past and reflect on the future

Mr. Eto shared his story with us, though he had been reluctant to talk about his experience for many years, not wanting to bring back those memories. I was shocked when he told us how he kept going past the dead bodies he came across on the river and the road. He said that his senses went numb and he didn’t feel anything. I felt strongly that we must take over his memories, as he asked, to learn from the past and reflect on the future. (Sayaka Kawata, 16)

Build peace with words, not force

Mr. Eto, who was talking about his horrific experience for the first time, stressed that peace must be built with words, not by force. Looking at the world, it seems difficult to realize mutual understanding through dialogue with other people and nations that hold different beliefs. But I’m concerned that unless we understand one another’s views and build cooperative relationships, such terrible events could happen again. (Ayumi Uehara, 16)

(Originally published on August 18, 2014)