Yoshiko Okabe, 90, Asakita Ward, Hiroshima

Jun. 25, 2015

Baby died in A-bomb aftermath

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way,” said Yoshiko Okabe, who realized her dream of becoming a businesswoman after the war.

For Ms. Okabe, 90, her experience of the atomic bombing was too painful to recount. For many years, she kept this experience to herself. However, with the thought that her account shouldn’t remain concealed, she chose to speak out in this interview.

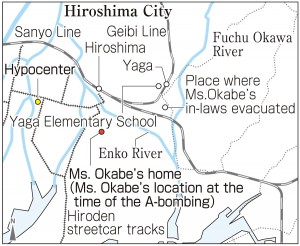

At the time of the bombing, Ms. Okabe was 21 years old. She was at home in Danbaranaka-machi, about 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, doing laundry. Hearing the sound of a U.S. B-29 bomber, louder than usual, she stepped out of the bathroom and was suddenly bathed in white light, accompanied by a great roar.

Ms. Okabe rushed to her daughter Hiroko, just eight months old, who had been sleeping in a small, tatami-mat room. She found Hiroko under the collapsed ceiling, staring blankly, not crying. Ms. Okabe took her daughter on her back and headed to Yagamachi (part of today’s Higashi Ward), where her husband’s family had evacuated earlier.

Along the way, Ms. Okabe wet a towel with water and wiped off Hiroko’s face, which had gotten covered with soot and dust. She tried to please the baby by singing a lullaby and bouncing her up and down on her back. Hiroko then waved her right hand from side to side. Ms. Okabe thought, “Hiroko can hear me. She’ll be okay. And I managed to survive, too.” Her baby brought her hope. And she discovered that her husband, who was working at a canning factory in Ujina-cho (in today’s Minami Ward), was safe, too.

At Yagamachi, one person per household was asked to go to Yaga National School, used as an aid station, to help care for the injured. Thus, Ms. Okabe went to the school every day, leaving Hiroko at home.

Around 3 p.m. on September 13, 1945, a woman from her neighborhood came to the school and said, “Something’s wrong with your baby! Please go home right away!” Ms. Okabe dashed home and found Hiroko unconscious, with her eyes closed. A doctor came from the school and gave the baby an injection, trying to revive her, but she didn’t respond and died a short time later.

According to her husband’s grandmother, who was over 80, Hiroko suffered diarrhea after the grandmother gave her canned mandarin oranges, supplied by the U.S. army, and let her eat her full. In a corner of the room was the empty can, rusted. Ms. Okabe couldn’t blame the old woman; she could only keep the pain of losing her daughter to herself. Hiroko’s body was cremated at a sandy patch by the Fuchu Okawa River and Ms. Okabe gathered her daughter’s ashes the following day.

After the war, she gave birth to four more children and then got divorced. While raising the children on her own, she worked and studied, obtaining nine certificates and licenses, becoming a beautician and mastering flower arrangement and calligraphy. She opened a beauty salon, and also worked as an instructor of kimono wearing. She even opened a video rental shop after turning 60 and realized her dream of being a businesswoman. With her words, “Where there’s a will, there’s a way,” she offers encouragement to today’s youth.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Learned importance of persistence

Ms. Okabe told us about her painful experience of the atomic bombing in a tearful voice. I thought she was remarkable because she obtained many certificates and tried to do a variety of things, one after the other, despite her sad past. I’ve always given up easily when I tried something. But I want to follow Ms. Okabe’s example and continue trying my best and find a lifetime interest, even if only one. (Nanase Shode, 14)

Want to move forward for my dream

“You are the owner of your dream. Because no one can control your dream, I’d like you to have a big dream,” Ms. Okada said to us. The more effort I make, the closer I can get to my dream. And in the end, my dream can come true. Holding her words to heart, and reminding myself of them from time to time, I want to move forward and realize my dream. (Ishin Nakahara, 15)

Hiroshima Insight

Yaga National School: An aid station in the A-bomb aftermath

Yaga National School (today’s Yaga Elementary School in Higashi Ward) was founded in 1872 when the modern school system was first established in Japan. Until a proper school building was constructed in 1897, the school used private locations, such as homes and temples. The school was relocated to its current site in 1934.

According to Record of the A-bomb Disaster in Yaga and Record of the A-bomb Disaster in Hiroshima, at the time of the atomic bombing, students in the third grade and above were evacuated in groups to Kochi (now part of Saeki Ward). The school, located about 3.7 kilometers from the hypocenter, suffered minor damage in the blast, including broken windows and cracks to the wall on the south side of the building, but avoided collapse and fire.

Consequently, the entire school grounds became an aid station to assist the survivors, right from the day of the bombing. Doctors treating patients were supported by civil defense volunteers, teachers and staff, and other citizens. They also helped cremate the dead on the school grounds and on the bank of the Fuchu Okawa River near the school. There were no unidentified victims because they had fled from the city center and their names or addresses were confirmed before they died.

The school building from that time continued to be used until it was razed by fire in 1955.

(Originally published on February 24, 2014)