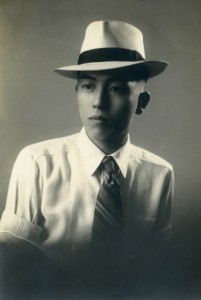

Kannichi Masui, 91, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Oct. 21, 2015

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

“If placed in extreme situations, even human beings can turn into demons,” said Kannichi Masui, 91. He still feels remorse 70 years after the day he was unable to help a dying boy who begged for water in the aftermath of the atomic bombing.

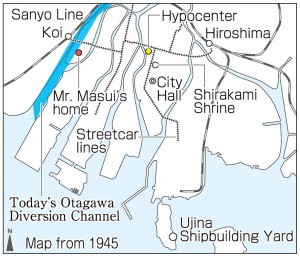

Mr. Masui was the eldest of four brothers. He was 21 years old when the atomic bomb exploded above the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. He was working at the Ujina shipbuilding yard (now part of Minami Ward), more than 4 kilometers from the bomb’s hypocenter. He had been assigned by a supervisor to help dismantle homes to create a fire lane on the morning of August 6.

That morning, he got on a streetcar at the stop near his home in the Fukushima-cho district (now part of Nishi Ward). When the streetcar arrived at the stop in front of Shirakami Shrine, where he was supposed to get off, he missed it because he had nodded off. However, not wanting to get off at the next stop and backtrack, he decided to head to the shipbuilding yard instead.

Back then, Mr. Masui was studying at what is known today as Kogakuin University, in Tokyo, and dreaming of designing landing craft for the military. “I felt some reluctance about going to the demolition site,” he recalls. Otemachi, the place where he had been assigned to engage in this work, was near the hypocenter. Considering this fact, he said that it can only be called a twist of fate that spelled the difference, for him, between life and death.

Soon after he sat down at his desk, feeling slightly ashamed about his decision, he saw a tremendous flash, then heard an enormous roar. He was catapulted into the air and struck by a flying window frame. He fell to the floor, his head bleeding badly.

His first thought was that the United States was dropping incendiary bombs. After he received first aid in an air raid shelter, there came an order to return home. At that point, he began the trek with a co-worker, Kumiko Nakakura, who was one year younger. Her house was in the city center. He soon realized that the damage was more horrific than what he imagined when he saw people with severe burns fleeing in an endless procession from the A-bombed area.

Chilled by this dreadful sight, Mr. Masui finally reached City Hall. It was then that he heard the quiet voice of a boy who had collapsed onto a fallen utility pole. “Water,” the boy was pleading.

Mr. Masui had no water bottle, but he was carrying a beer bottle that was filled with water. Yet he instinctively hid the bottle and moved on.

Fierce flames that day prevented Mr. Masui and Ms. Nakakura from returning to their homes. In the end, he never drank any of the water in that beer bottle. “Even though I was also in peril,” he said, “I should have felt mercy for the boy as he lay there dying and given him some water.” Every year on August 6, he remembers the boy and sheds tears of regret.

The following day, Mr. Masui couldn’t leave Ms. Nakakura by herself, who was shivering with fear, and he helped her look for her family. They found her mother and nephew at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, where conditions were hellish. He then made his way back home. When he arrived, he found that his family were injured but safe.

“Before the atomic bombing, I had faced a lot of difficulties, too. However, I was able to overcome them with my dogged nature, which came from my father,” said Mr. Masui, recalling his younger days. His father was one of the founding members of Hiroshima-ken Suiheisha, an association established in 1923 which fought discrimination of the class known as buraku. As members of this organization, his family suffered from oppression and their lives were never easy. The bomb had also leveled their house and they were forced to begin again by building a shack.

Mr. Masui later married Ms. Nakakura, who lost her mother five days after the atomic bombing. The year after the war ended, he opened a small butcher shop with his parents and brothers. The shop has since grown into a large meat dealer.

Although he wrote down his account of the atomic bombing to pass on his thoughts and feelings to his grandchildren, he had never shared his experience with other people. This year, though, he had a change of heart about relating his story because the passing of another decade will mark the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing and his 101st birthday. He then broke the ice by sharing his experience at the Hiroshima Pen Club, where he once served as director.

Mr. Masui lost his mother, his wife, and two younger brothers to cancer, and he has been suffering from a thyroid tumor himself. “The U.S. should be criticized for dropping such a destructive bomb in a residential area, rather than a battlefield,” he said firmly. “Hiroshima was a burnt plain after the atomic bombing, and it was said that nothing would grow here for 70 years. But the survivors, who rebuilt Hiroshima from the ruins while suffering from the damage caused by the bomb, brought prosperity to the city. I hope that young people will come to understand this fact and the tireless efforts made by the A-bomb survivors.”

Many roles that young people can play

Mr. Masui was supposed to get off the streetcar at a stop near the hypocenter. But he didn’t do so because he was napping and, as a result, he escaped death. He said that he hadn’t told anyone about his A-bomb experience because it was such a terrible memory. Because we had the chance to meet Mr. Masui, who’s now 91, and hear his story, I realized that there are many roles that we, the junior writers, can play in this area. (Miki Meguro, 12)

Survivors left with deep psychological scars

Mr. Masui didn’t respond to a boy who wanted water after the bombing, and he still feels remorse over that incident, even 70 years later. It struck me deeply when he said that the atomic bomb had pushed human beings to their limits, and when placed in such extreme situations, we can become evil. It was like that young and hearty man inside him had tears in his eyes. I realized that the atomic bomb left deep psychological scars on the survivors. (Marika Tsuboki, 15)

Learning to live a strong life, too

Mr. Masui told us that he was living in a relative’s house and working there when he was a child and that his neighbors helped him when his family lost their home because of the bombing. I was impressed by his words, “Every effort is worthwhile.” I’d like to learn from Mr. Masui, who has lived a strong life to the age of 91. I realized clearly that the people of Hiroshima had to overcome terrible hardships to rebuild the city. (Takeshi Iwata, 17)

(Originally published on October 12, 2015)

Remorse still felt, 70 years after the atomic bombing

“If placed in extreme situations, even human beings can turn into demons,” said Kannichi Masui, 91. He still feels remorse 70 years after the day he was unable to help a dying boy who begged for water in the aftermath of the atomic bombing.

Mr. Masui was the eldest of four brothers. He was 21 years old when the atomic bomb exploded above the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. He was working at the Ujina shipbuilding yard (now part of Minami Ward), more than 4 kilometers from the bomb’s hypocenter. He had been assigned by a supervisor to help dismantle homes to create a fire lane on the morning of August 6.

That morning, he got on a streetcar at the stop near his home in the Fukushima-cho district (now part of Nishi Ward). When the streetcar arrived at the stop in front of Shirakami Shrine, where he was supposed to get off, he missed it because he had nodded off. However, not wanting to get off at the next stop and backtrack, he decided to head to the shipbuilding yard instead.

Back then, Mr. Masui was studying at what is known today as Kogakuin University, in Tokyo, and dreaming of designing landing craft for the military. “I felt some reluctance about going to the demolition site,” he recalls. Otemachi, the place where he had been assigned to engage in this work, was near the hypocenter. Considering this fact, he said that it can only be called a twist of fate that spelled the difference, for him, between life and death.

Soon after he sat down at his desk, feeling slightly ashamed about his decision, he saw a tremendous flash, then heard an enormous roar. He was catapulted into the air and struck by a flying window frame. He fell to the floor, his head bleeding badly.

His first thought was that the United States was dropping incendiary bombs. After he received first aid in an air raid shelter, there came an order to return home. At that point, he began the trek with a co-worker, Kumiko Nakakura, who was one year younger. Her house was in the city center. He soon realized that the damage was more horrific than what he imagined when he saw people with severe burns fleeing in an endless procession from the A-bombed area.

Chilled by this dreadful sight, Mr. Masui finally reached City Hall. It was then that he heard the quiet voice of a boy who had collapsed onto a fallen utility pole. “Water,” the boy was pleading.

Mr. Masui had no water bottle, but he was carrying a beer bottle that was filled with water. Yet he instinctively hid the bottle and moved on.

Fierce flames that day prevented Mr. Masui and Ms. Nakakura from returning to their homes. In the end, he never drank any of the water in that beer bottle. “Even though I was also in peril,” he said, “I should have felt mercy for the boy as he lay there dying and given him some water.” Every year on August 6, he remembers the boy and sheds tears of regret.

The following day, Mr. Masui couldn’t leave Ms. Nakakura by herself, who was shivering with fear, and he helped her look for her family. They found her mother and nephew at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, where conditions were hellish. He then made his way back home. When he arrived, he found that his family were injured but safe.

“Before the atomic bombing, I had faced a lot of difficulties, too. However, I was able to overcome them with my dogged nature, which came from my father,” said Mr. Masui, recalling his younger days. His father was one of the founding members of Hiroshima-ken Suiheisha, an association established in 1923 which fought discrimination of the class known as buraku. As members of this organization, his family suffered from oppression and their lives were never easy. The bomb had also leveled their house and they were forced to begin again by building a shack.

Mr. Masui later married Ms. Nakakura, who lost her mother five days after the atomic bombing. The year after the war ended, he opened a small butcher shop with his parents and brothers. The shop has since grown into a large meat dealer.

Although he wrote down his account of the atomic bombing to pass on his thoughts and feelings to his grandchildren, he had never shared his experience with other people. This year, though, he had a change of heart about relating his story because the passing of another decade will mark the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing and his 101st birthday. He then broke the ice by sharing his experience at the Hiroshima Pen Club, where he once served as director.

Mr. Masui lost his mother, his wife, and two younger brothers to cancer, and he has been suffering from a thyroid tumor himself. “The U.S. should be criticized for dropping such a destructive bomb in a residential area, rather than a battlefield,” he said firmly. “Hiroshima was a burnt plain after the atomic bombing, and it was said that nothing would grow here for 70 years. But the survivors, who rebuilt Hiroshima from the ruins while suffering from the damage caused by the bomb, brought prosperity to the city. I hope that young people will come to understand this fact and the tireless efforts made by the A-bomb survivors.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Many roles that young people can play

Mr. Masui was supposed to get off the streetcar at a stop near the hypocenter. But he didn’t do so because he was napping and, as a result, he escaped death. He said that he hadn’t told anyone about his A-bomb experience because it was such a terrible memory. Because we had the chance to meet Mr. Masui, who’s now 91, and hear his story, I realized that there are many roles that we, the junior writers, can play in this area. (Miki Meguro, 12)

Survivors left with deep psychological scars

Mr. Masui didn’t respond to a boy who wanted water after the bombing, and he still feels remorse over that incident, even 70 years later. It struck me deeply when he said that the atomic bomb had pushed human beings to their limits, and when placed in such extreme situations, we can become evil. It was like that young and hearty man inside him had tears in his eyes. I realized that the atomic bomb left deep psychological scars on the survivors. (Marika Tsuboki, 15)

Learning to live a strong life, too

Mr. Masui told us that he was living in a relative’s house and working there when he was a child and that his neighbors helped him when his family lost their home because of the bombing. I was impressed by his words, “Every effort is worthwhile.” I’d like to learn from Mr. Masui, who has lived a strong life to the age of 91. I realized clearly that the people of Hiroshima had to overcome terrible hardships to rebuild the city. (Takeshi Iwata, 17)

(Originally published on October 12, 2015)