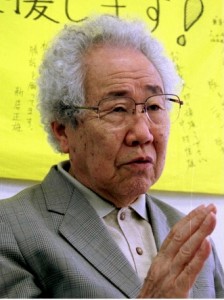

Messages from A-bomb Survivors: Koichi Yasui, Part 1

Dec. 7, 2010

Koichi Yasui, 77, Sapporo, Hokkaido

Anger over process of A-bomb disease certification

Note: This series first appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in 2001.

Deeply shaken by death of mother and baby

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, I came upon a woman who had just given birth in the shade of a tree. She was tearing at her tattered clothes with severely burned hands, trying to swaddle her baby with the fabric. But her strength must have failed. She wilted to the ground, and then lay still. I didn’t hear the newborn cry, either.

It was a tremendous shock to me. I got angry at myself, because I couldn’t do anything for them. Because of the atomic bombing, the mother and her baby couldn’t even die as human beings. I was a soldier at the time, but I vowed that I would never condone war.

Mr. Yasui experienced the atomic bombing at the military barracks of the former Army Ship Communications Reserve in Minami-machi, about 1.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. He engaged in relief efforts for the injured and helped to cremate the dead. At the end of August, he returned to his hometown in Hokkaido. In 1954, he landed a teaching position at a junior high school.

All A-bomb survivors express remorse for having lived through the catastrophe themselves while leaving others in need to their fates. After I returned to my parents’ home in Otaru, I fell into a listless state. Days went by. I was haunted by an encounter with a boy who lay dying at Hijiyama Hill. He said to me, “Soldier, please get revenge for me.” His whole body had turned red from the severe burns he suffered.

After I started working as a teacher, I was beset by a series of health problems. I had a heart attack, a cataract, hepatitis, and so on. To date, I’ve been hospitalized 22 times. I’m like a department store of disease. Around 1980, when I was ready to resign from my school, even climbing up and down the stairs to the third floor of the building was an effort. As I didn’t want to cause any inconvenience to my students, I quit five years before I would have retired.

In 1984, Mr. Yasui obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and began to help the A-bomb survivors’ association in Hokkaido with its work.

I got angry as I was trying to help A-bomb survivors apply for the A-bomb disease certification, because so many of their applications were getting rejected. The screening process moves so slowly, and the decision is finally made based on the distance between the hypocenter and the survivor’s location at the time of the bombing. It’s just absurd to draw a line like that and turn down these applications on the grounds that the applicants experienced the bombing at a location more than two kilometers from the hypocenter. The Dosimetry System 1986 (DS86), which estimates the radiation dose suffered by a survivor and is used as the criteria for the judgment, is clearly unreliable.

At the time of the bombing, I was wearing a watch and I recorded when and where I was in the aftermath. Using this information, Shoji Sawada, a professor emeritus at Nagoya University, estimated the level of radiation I suffered. His estimate was 10 to 18 times higher than the dose calculated using DS86. Though the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has presented new criteria for A-bomb disease certification, this is pointless as long as DS86 is automatically used in the screening process.

In 1996, Mr. Yasui developed prostate cancer. He applied for A-bomb disease certification, but his application was rejected. In response, Mr. Yasui filed a lawsuit at the Sapporo District Court in October 1999.

Because of my age, I hesitated to file a lawsuit. In the Matsuya case, originally filed in Nagasaki Prefecture, it took the plaintiff, A-bomb survivor Hideko Matsuya, more than ten years to win at the Supreme Court. When I die, the legal battle will be over. But lawyers and all sorts of people have given me their support.

Pride at stake in lawsuit

I didn’t do it for the money. It was a matter of pride as an A-bomb survivor. If I have to die in the end, anyway, I want my children and grandchildren to remember that I died because of A-bomb disease. I want them to know that I didn’t die from ordinary cancer, and to ingrain in their minds that, for this reason, nuclear weapons must never be used.

The catalyst for my lawsuit and my peace efforts is my resolve never to forgive the atomic bombing, which deprived people of the barest of their human rights, like the mother and baby that I saw after the bombing. Ultimately, I believe the issues involving the atomic bombing are issues of human rights.

(Originally published on August 3, 2001)

Anger over process of A-bomb disease certification

Note: This series first appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in 2001.

Deeply shaken by death of mother and baby

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, I came upon a woman who had just given birth in the shade of a tree. She was tearing at her tattered clothes with severely burned hands, trying to swaddle her baby with the fabric. But her strength must have failed. She wilted to the ground, and then lay still. I didn’t hear the newborn cry, either.

It was a tremendous shock to me. I got angry at myself, because I couldn’t do anything for them. Because of the atomic bombing, the mother and her baby couldn’t even die as human beings. I was a soldier at the time, but I vowed that I would never condone war.

Mr. Yasui experienced the atomic bombing at the military barracks of the former Army Ship Communications Reserve in Minami-machi, about 1.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. He engaged in relief efforts for the injured and helped to cremate the dead. At the end of August, he returned to his hometown in Hokkaido. In 1954, he landed a teaching position at a junior high school.

All A-bomb survivors express remorse for having lived through the catastrophe themselves while leaving others in need to their fates. After I returned to my parents’ home in Otaru, I fell into a listless state. Days went by. I was haunted by an encounter with a boy who lay dying at Hijiyama Hill. He said to me, “Soldier, please get revenge for me.” His whole body had turned red from the severe burns he suffered.

After I started working as a teacher, I was beset by a series of health problems. I had a heart attack, a cataract, hepatitis, and so on. To date, I’ve been hospitalized 22 times. I’m like a department store of disease. Around 1980, when I was ready to resign from my school, even climbing up and down the stairs to the third floor of the building was an effort. As I didn’t want to cause any inconvenience to my students, I quit five years before I would have retired.

In 1984, Mr. Yasui obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and began to help the A-bomb survivors’ association in Hokkaido with its work.

I got angry as I was trying to help A-bomb survivors apply for the A-bomb disease certification, because so many of their applications were getting rejected. The screening process moves so slowly, and the decision is finally made based on the distance between the hypocenter and the survivor’s location at the time of the bombing. It’s just absurd to draw a line like that and turn down these applications on the grounds that the applicants experienced the bombing at a location more than two kilometers from the hypocenter. The Dosimetry System 1986 (DS86), which estimates the radiation dose suffered by a survivor and is used as the criteria for the judgment, is clearly unreliable.

At the time of the bombing, I was wearing a watch and I recorded when and where I was in the aftermath. Using this information, Shoji Sawada, a professor emeritus at Nagoya University, estimated the level of radiation I suffered. His estimate was 10 to 18 times higher than the dose calculated using DS86. Though the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has presented new criteria for A-bomb disease certification, this is pointless as long as DS86 is automatically used in the screening process.

In 1996, Mr. Yasui developed prostate cancer. He applied for A-bomb disease certification, but his application was rejected. In response, Mr. Yasui filed a lawsuit at the Sapporo District Court in October 1999.

Because of my age, I hesitated to file a lawsuit. In the Matsuya case, originally filed in Nagasaki Prefecture, it took the plaintiff, A-bomb survivor Hideko Matsuya, more than ten years to win at the Supreme Court. When I die, the legal battle will be over. But lawyers and all sorts of people have given me their support.

Pride at stake in lawsuit

I didn’t do it for the money. It was a matter of pride as an A-bomb survivor. If I have to die in the end, anyway, I want my children and grandchildren to remember that I died because of A-bomb disease. I want them to know that I didn’t die from ordinary cancer, and to ingrain in their minds that, for this reason, nuclear weapons must never be used.

The catalyst for my lawsuit and my peace efforts is my resolve never to forgive the atomic bombing, which deprived people of the barest of their human rights, like the mother and baby that I saw after the bombing. Ultimately, I believe the issues involving the atomic bombing are issues of human rights.

(Originally published on August 3, 2001)